The force of the wind was so great, it stripped bark from the trees. The Albury Donnies, a fleet of 18 boats that have ferried children to school, and their parents to work, every day since 1959—even after Hurricane Floyd in ‘99, even after the one-two punch of Frances and Jeanne in ‘04—sank into the sea. The Mudd, the largest Haitian immigrant settlement in the Bahamian Abaco Cays—where thousands live, and tourists never visit—vanished almost as quickly. Dorian, reportedly the strongest hurricane on modern record to hit the Bahamas, took everyone by surprise. “Reporters were on the beach, filming to-camera type-stuff that you see all the time on US and European networks,” Eugene Duffy, the managing editor of The Tribune, in Nassau, the capital, says. “No one thought, ‘Oh my God, it is going to be 250 mile an hour gusts or water 25 feet above sea level.’”

Duffy sent a reporter and a photographer to Marsh Harbour, a large town in the Abacos, two days before Dorian struck. They stayed at the Abaco Beach Resort, where they would have back-up generators and accomodations above the usual storm surge line. But they have not been in touch with Duffy since Sunday evening, when they told him some rooms at the hotel were flooded. After a day without word, Duffy reached out to friends at Eyewitness News, who said the pair were last seen seeking refuge at a government shelter.

ICYMI: The difficulties of covering Hurricane Dorian

With his reporters on the ground unable to file, Duffy’s team back in Nassau, 100 miles south, has relied almost entirely on social media for details about Dorian’s impact. “You can still plunder all the human interest stories, footage, voice recordings,” Duffy says. But his staff has to filter for misinformation. “The Bahamas is a weird place,” he says. “Bahamians love a rumor, which turns into a ‘fact’ in two minutes, and then you won’t convince them otherwise.”

On Monday, drone footage believed to have been taken of Marsh Harbour that day circulated on social media. “It was a fantastical wipe-out,” Duffy says. “But within five minutes, three of us had made independent source checks, and it wasn’t true.” On a community Facebook page, residents of Treasure Cay, a narrow curl of land 16 miles further along Dorian’s path from Marsh Harbour, posted conflicting information about who was missing. One woman’s search for her grandson was fake, some neighbors warned, the work of “trolls.” And when a photo circulated of two lifeless bodies on a flatbed truck, Duffy chose not to publish it. “At this moment, you know, people are still desperate for news,” he explains. “Literally thousands of people haven’t been in touch with relatives and friends.” He didn’t want every Tribune reader to suspect that the image showed the bodies of their own loved ones.

Other journalists, tapping into a high-speed mobile network new to the Bahamas, have been able to use WhatsApp to coordinate rescue efforts and conduct interviews. Jasper Ward, of the Nassau Guardian, was on the phone with a woman named Gertha Joseph when the roof above her blew off. A neighbor placed Joseph’s four-month-old baby in a plastic tub and swam with him through a 20-foot surge to dry land. Then he returned to help Joseph, who does not know how to swim.

By midweek, the death toll was seven, but expected to grow. There have been no recovery efforts in high-risk areas like The Mudd. “There’s been no chance to look for bodies in cars, bodies under collapsed buildings,” Duffy says. “At the moment it’s about gathering all the humans together and moving them into the safe areas.” The government is moving cautiously, starting with an initial assessment of the Abacos by flyover. Philip Edward “Brave” Davis, who leads the Bahamian opposition party, took a flight to review the wreckage and Duffy, still uncertain about the status of his first reporter on the scene, sent another up with Davis on the plane.

Duffy worries about the international media’s inevitable arrival. “The world press will all be itching to get in and do their live broadcast from the flooded streets,” he says. But there’s nowhere for rescuers to stay once they arrive, much less reporters. And their presence will be a burden on what’s left of the feeble infrastructure, Duffy adds, when islanders would rather resources go to assist the Royal Navy’s auxiliary supply ship, said to be on its way, the three or four US Coast Guard vessels en route, and a single helicopter being used to transport stranded Bahamians.

In the meantime, the Tribune has been a go-to source of information for journalists trying to gather Dorian news. Within hours, interest in the hurricane flipped the Tribune’s print-focused business model: “Normally I have one guy on digital, and we have a daily audience of 25,000 unique visitors,” Duffy says. Since Dorian hit, the Tribune has had a daily audience of 100 thousand unique visitors—a number Duffy has seen only once before, in 2014, when Myles Munroe, a Bahamian preacher and motivational speaker, died in a plane crash en route to Nassau.

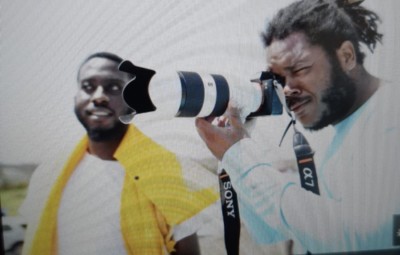

Reporter Rashad Rolle and photographer Terrel Carey in a photograph that Bahamian police sent confirming their safety after the storm. Photo/ Eugene Duffy

On Wednesday afternoon, the Bahamas Police Superintendent confirmed that Duffy’s reporters are OK. “They are safe,” a text read. “When I received that three-word text from the superintendent, it was one of those moments of immense relief,” Duffy says. “I’m sure they’re going to be fine,” he adds. But he doesn’t know when to expect more news. By the time they file, they will have embedded with the Marsh Harbour community for at least 100 hours—through Dorian’s approach, its hold on the town, and the initial efforts to comprehend its toll. Now that emergency teams are arriving, Duffy hopes the wait for their story is almost over.

ICYMI: Meteorologists to newsrooms: Hurricane impacts defy categorization

Amanda Darrach is a contributor to CJR and a visiting scholar at the University of St Andrews School of International Relations. Follow her on Twitter @thedarrach.