Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

The latest episode of The New Yorker’s playful online video series The Cartoon Lounge offers a look at how an illustration makes it into the country’s most storied magazine. In the clip, artists pitch their work, often in vain, to cartoon editor Bob Mankoff. One piece, lacking a caption, depicts a wooden Trojan cat attempting to infiltrate a doghouse. “It’s wide open to interpretation,” the cartoonist says. Mankoff, effectively signing the sketch’s death warrant, responds, “I think maybe a little too wide open.”

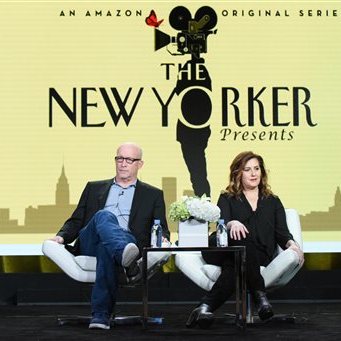

The Cartoon Lounge is just one way in which The New Yorker’s video offerings have expanded in the last 18 months. Since senior video editor Catherine Spangler, previously of The New York Times, joined the magazine about nine months ago, the website has boosted its output to 10 to 20 clips per month, garnering an average of 530,000 onsite monthly views. A new Amazon Prime magazine series called The New Yorker Presents is also making noise. Its 30-minute episodes include humorous shorts, brief nonfiction pieces, and documentaries inspired by the magazine’s feature stories. Like The Cartoon Lounge, a number of clips, both on the website and on Amazon, spotlight the inner workings of the magazine, displaying the elevated humor and lofty editorial standards that define it.

The New Yorker is evolving to take on an internet that is also changing through new social media, video streaming services, and podcasts. But for a magazine that has been known for standing apart from–and above–the competition, that evolution can also be risky. Will The New Yorker stray from its high standards, take on too much at once, or fail to grasp the subtleties of a new medium?

What once went on behind office doors of The New Yorker typically remained there. Of course, plenty of histories and memoirs have been published, like the 1975 book Here At The New Yorker, but they are said to have irked some staffers. “The New Yorker was always trying to protect its mystique,” says Adam Van Doren, who made the documentary Top Hat and Tales: Harold Ross and the Making of The New Yorker. “It added to a unique quality. It was mysterious.”

Editor William Shawn oversaw a period of time in which the magazine was “militantly opaque,” from 1951 to 1987, says Ben Yagoda, author of About Town: The New Yorker And The World It Made. Under Shawn, editions went to newsstands without a table of contents or bylines. He also sought to publish journalism that would “avoid topicality at all costs,” a goal that’s been abandoned for some time. The last vestige of the eccentric sense of mystery that characterized Shawn’s New Yorker, Yagoda contends, is the absence of a masthead.

Now, several doors welcome fans inside the shop. In addition to The Cartoon Lounge, there’s Comma Queen, which features copy editor Mary Norris doling out grammar and style lessons. She bases her installments on The New Yorker’s enshrined practices and examples of actual revisions. Inside-baseball content fills the publication’s Snapchat feed, from the story behind the print magazine’s weekly cover art to bite-sized movie reviews filmed while a critic strolls through its offices at One World Trade Center. In transitioning between segments, the Amazon series employs clips that show how the fact-checking department operates or take viewers into the magazine’s archival shelves.

Instead of what editor David Remnick calls the “sort of faux secretiveness” of the past, readers can find pleasure in these small glimpses. Remnick compares them to The Paris Review’s interviews with famous writers, which long ago helped him form connections with some of his favorite literary figures. Some questions dug into deep, philosophical issues, but others focused on the simple and humanizing details of writing: whether the author used a pen or a pencil, or how Vladimir Nabokov wrote his novels on index cards. That’s what’s happening now, to some degree, at The New Yorker. “If Cartoon Lounge manages to both be funny and give you a glimpse of the lunatic asylum that is the cartoon department, I think that’s okay,” Remnick says.

Pulling back the curtain is just one component of the magazine’s video effort. It is adapting the traditions that built its 90-plus-year legacy to online video, a medium that many news outlets approach in terms of quantity rather than quality. The New Yorker started building its video team in 2013, hiring two video producers who focus on mini documentaries, companion clips for written pieces, and short fiction. The DNA of this content remains consistent with that of the print product, relying on deep reporting, captivating characters, and intelligent analysis to tell each story. “The biggest challenge is meeting the bar of a New Yorker story,” says Spangler, “because it’s so high.”

To do that, The New Yorker has drawn video talent that’s comparable to the quality of its writers. Alex Gibney, whose film Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief won three Emmys last year, is the executive producer of the Amazon series; Kahane Cooperman, formerly of The Daily Show, is showrunner. The website, meanwhile, has published work from respected filmmakers like Gabe Polsky, the force behind the 2014 documentary Red Army, which centered on a Soviet hockey team. The magazine is also partnering with WNYC to produce a weekly audio program, The New Yorker Radio Hour, hosted by Remnick.

So far, traffic numbers suggest that these experiments are succeeding, or at least drawing notice. From the start of 2016 to last week, the publication had already amassed 1.3 million views, up by more than 300 percent from the same time last year, according to the magazine’s analytics team. The website as a whole hit an all-time traffic high when it reached more than 16 million unique visitors in January.

Remnick says the magazine’s deals with Amazon and WNYC have “some positive business aspects,” though they’re modest; a spokeswoman declined to disclose financial details. But the bigger aims are to embrace existing fans and draw new readers who, Remnick posits, will likely be young. Longtime readers get something else. In its video-recorded transparency, The New Yorker reconfirms its commitment to the magazine’s journalistic, comedic, and literary foundations. Fact-checkers still tediously confirm every word; in one video, an in-house librarian celebrates the bygone contributions of writers like Truman Capote, J.D. Salinger, and Mary McCarthy.

It seems likely that the magazine’s longstanding legacy and its ambitious aspirations can help to advance each other. That may come at the sacrifice of some of the intrigue that surrounded the magazine in years gone by, but times have changed. “The old commercial way of publishing The New Yorker, where you did the magazine in a pre-internet, pre-Craigslist way in which there was all that retail advertising that you would see in a typical October issue of The New Yorker in 1965, that’s Jurassic Park,” Remnick says. “That’s an ancient world.”*

*An earlier version of this story included a truncated quote that incorrectly implied that retail advertising is no longer critical to The New Yorker. The full quote has been restored.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.