Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

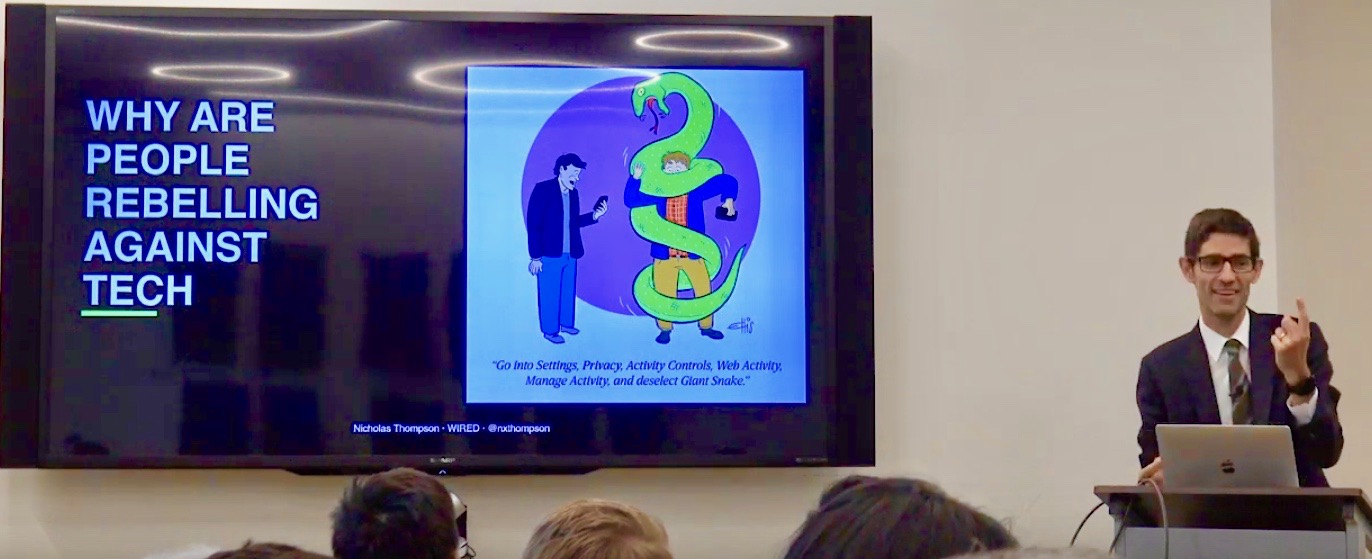

In early October, Nicholas Thompson, editor in chief of Wired, gave a pair of talks about the current techlash at Stanford University—a place he described as a high-trust environment. “We can leave our bag outside and nobody’s going to steal it, right?” he said. “It just makes everything easier.” Low-trust environments, it stands to reason, make things harder. These days, the internet seems to be, increasingly, a low-trust environment.

Thompson dates the start of the techlash to the 2016 US elections. Since then, he told his Stanford audience, “there’s not one person in Washington who talks positively about the tech companies.” Republicans accuse social-media platforms and search engines of partisan bias; Democratic presidential candidates want to break them up. Mistrust isn’t confined to elected officials. Survey data published in September by Vox found widespread support—“across most age groups, education levels, demographics, and political ideologies”—for greater antitrust regulation against large tech companies.

One such company, Facebook, which has most recently come under fire for its decision not to fact-check political ads on its platform, would seem to confirm Thompson’s tech-lash start date. In internal conversations, leaked to and published by The Verge, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg said in its early days the platform “got more glowing press than I think any company deserves. And it wasn’t just Facebook; it was the whole tech industry. And then I think a lot changed in the last few years, and especially since the 2016 elections.” In those conversations, Zuckerberg suggested increased criticism of Facebook focused on the company’s perceived motives, be they financial or political. “I think it’s tough to break down these perceptions and build trust until you get to a place where people know that you have their best interests at heart,” Zuckerberg said.

ICYMI: How newsroom managers should approach union organizing

As Thompson sees it, earlier and more benevolent philosophies of the internet—the notion that everything needed to be free—have given rise to what critics call the surveillance economy. “The way you monetize information on the Internet—if you’re not going to sell it, you’re not going to ask people to pay—is you track all their data.” Thompson said: “You figure out everything you can about them. You build ever more impressive data sets that allow you to sell ever more hyper-targeted ads.”

If there’s an upshot, Thompson said, then it’s increased concern for our own privacy. He recalled a personal moment of concern when he realized Facebook’s “People You May Know” feature cross-referenced contacts, including journalistic sources, in his address book. The feature, Thompson said, could potentially recommend his sources to their bosses. “Not great.”

People also are coming to realize that many devices and apps appear to work at cross-purposes with our better selves, Thompson said. He cited data from the Center for Humane Technology, which gathered information on app use and happiness from 200,000 people. (“Happy” Facebook users, for instance, spent an average of 22 minutes per day on the platform; “unhappy” users spent an average of 59 minutes per day.) Such realizations, Thompson said, have had a big effect and changed the public’s perception of Silicon Valley. The public, he said, recognizes that “the smartest people in the world are here.” Now, however, there is increased concern that Silicon Valley is “building stuff that we regret using, meaning they’re somehow figuring out how to trick our better selves into wasting time so they can monetize it more.”

One of the great challenges in engineering, Thompson said, “is to increase trust levels.” Computers, he noted, have always exceeded us on smaller, even trivial matters of intelligence: a game of chess, the ability to do math. “But now there’s an uneasiness that machines will exceed us in the ability to do more creative tasks,” he said. “There’s a societal perception that we’re losing human agency, that we’re about to be replaced.”

THE KICKER: CJR’s public editors, one year out from 2020

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.