Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

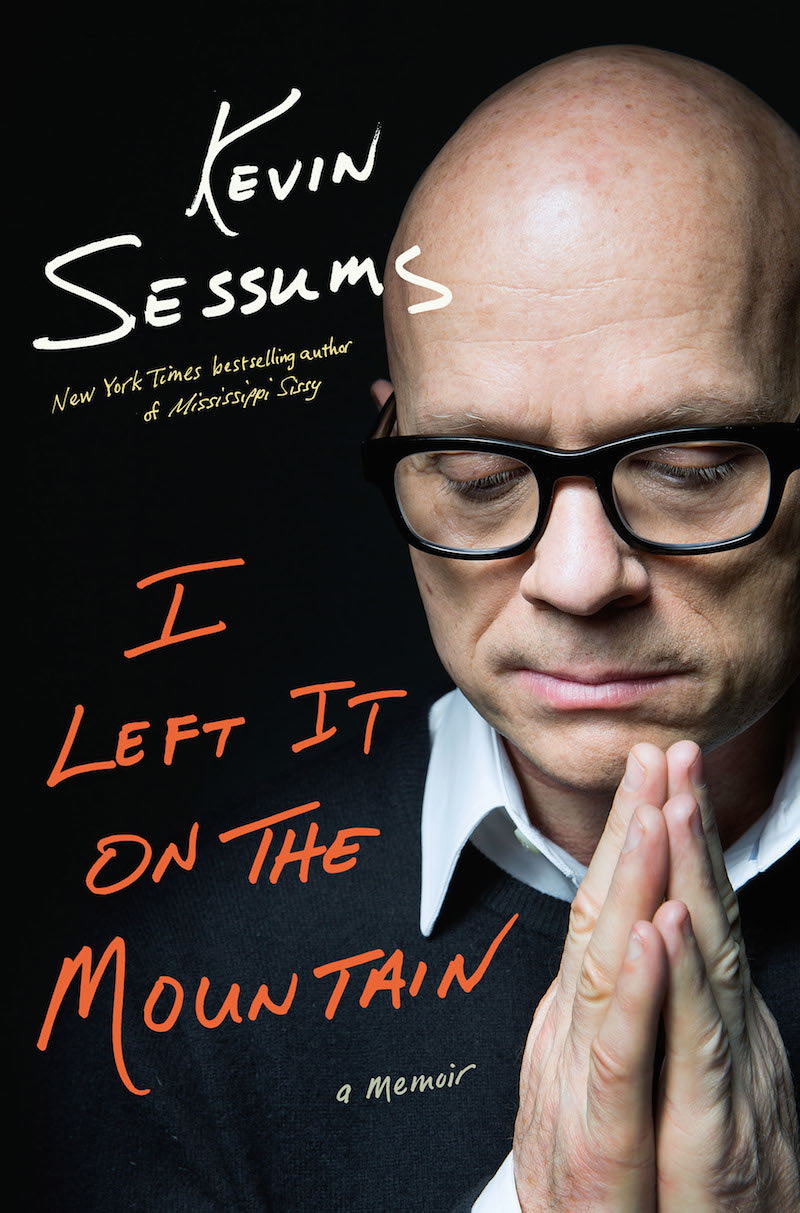

I Left It On the Mountain

By Kevin Sessums

St. Martin’s Press

288 pages, $25.99

In Kevin Sessums’ 2007 coming-of-age memoir, Mississippi Sissy, an early mentor describes the demeanor that would contribute to Sessums’ success as a celebrity interviewer for Vanity Fair, Parade, and other publications:

“Don’t ask me why,” Frank Hains, a newspaper editor, theater columnist, and stage director, tells the teenage Sessums, “but I trust you completely. You are remarkably free of judgment and yet you are preternaturally wary. It’s a nice combination. You seem to be spying right there out in the open all the time, right there in our midst…. It’s quite disarming.”

In the company of Hains, whose literary circle included Eudora Welty, Sessums remembers enjoying a rare respite from loneliness. Mississippi Sissy won praise as an assured, richly detailed narrative of a gay youth’s encounters with love and death.

But it’s a work that hints at the narrator’s unreliability. In an author’s note, Sessums writes of the rich, novelistic conversations he recreates: “The dialogue—as true to these people and events and what was said around me as my memory can possibly make it—is my own invention. I was not carrying around a recording device when growing up in Mississippi. But what I did have, even then, was my writer’s ear. I listened.”

Another warning is a legal disclaimer on the copyright page, not a typical one for a memoir: “This is a work of fiction.* All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in the novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.” This seems to contradict another assertion in the author’s note: “All the people and the names are real. All the events actually occurred.”

So what exactly are we to believe? Even if the dialogue is invented or embellished, can Sessums be trusted on the core facts, or at least the emotional truth, of his story? Are his comments on his own reliability as a narrator credible? And how do these doubts influence our reading of his less polished, and even more graphic, second memoir, I Left It on the Mountain?

If Mississippi Sissy was a classic Bildungsroman with tragic Dickensian undercurrents, I Left It on the Mountain is a clumsy mash-up of several currently popular memoir forms: the addiction struggle, the quest for redemption, the walk in the wilderness. It lurches backward and forward in time, repeating some material from the first memoir. Awkwardly written and confusingly structured, it does achieve the dubious feat of plunging readers deep into Sessums’ fragile, conflicted psyche.

Sessums’ middle-age troubles include a positive HIV status; concurrent addictions to crystal meth and promiscuous, anonymous, violent sex; and the resulting decimation of his career and bank account.

His struggles can likely be traced, at least in part, to the shattering events of his rural Mississippi childhood—horrific even by Southern Gothic standards. By the age of 8, he had lost both parents: his often gruff, disciplinarian father to an auto accident, and his beloved mother to cancer. He and his younger brother and sister were raised by their maternal grandparents, both politically conservative and racist in the fashion of their time and place. A black housekeeper named Matty May, who adored Sidney Poitier and schooled Sessums on race relations, supplied a dose of maternal warmth. But Sessums recounts feeling like a misfit, set apart by his emerging sexuality, his literary inclinations, and his liberal politics.

The boy’s fatherlessness and isolation were catnip to a pedophilic preacher, who molested him on at least two occasions when he was 13. Two years earlier, Sessums had been the victim of a sexual assault by a stranger in a movie theater showing (perhaps too neatly) the 1967 thriller Wait Until Dark. His youth ended with another excruciating, violent loss—the murder of his friend and mentor Hains. Soon afterward he decamped to the Juilliard School to train as an actor, which is where the first memoir left us.

Sessums’ arrival in New York offered a welcome introduction to a more cosmopolitan world. Older gay men—beginning with Henry Geldzahler, the city’s commissioner of cultural affairs—invited him into their social circles. Through Geldzahler, he “gained entry into the Manhattan of private screenings, gallery openings, uptown parties, downtown dinners at Odeon….'” But Sessums’ traumatic past, sometimes suppressed, never entirely receded; he used it to inform his work—his acting, the celebrity interviews, the first memoir. And then it overtook him.

One of the new memoir’s two epigraphs is a quotation drawn from an 1819 letter by the poet John Keats: “Do you not see how necessary a world of pains and trouble is to school an intelligence and make it a soul?” In Sessums’ case, his vulnerability was paired with an almost obsessive attraction to celebrity, and comfort with it. Along with his acting experience and connections gleaned from a stint as a factotum at Paramount Pictures, those qualities helped him find common ground with others who, beneath their stardom and allure, also were hurting.

In explaining the connection, Sessums says much of his childhood was spent “seeking the comfort I felt nesting in the presence of such creatures on the television or in the movies.” As a boy, he held “secret conversations” with stars, “imagining they were the ones who understood how trapped I felt in my otherness, in the Mississippi countryside, in my grief.”

Moving from Paramount to Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine, and then Vanity Fair, Sessums found a career that seemed an ideal emotional fit: “At the very moment when I alighted in the nest that a conversation with a celebrity created, I became that comforted child once more…. With someone famous, I could be my truest self.”

Sessums cultivated a diverse circle of what he calls “heightened acquaintances.” Madonna, Courtney Love, Michael J. Fox, Daniel Radcliffe, Hugh Jackman, Diane Sawyer, Tom Cruise, Michelle Williams, and Jessica Lange are among the names he drops. The memoir’s second epigraph is an excerpt from a 1983 letter to Sessums from the poet Howard Moss: “[Y]ou seem to be known by everyone.”

At one point, Sessums declares that he “came to define” celebrity journalism, but he quickly denigrates the accomplishment. While Warhol’s Factory epitomized “tacky glamour,” at Vanity Fair, “[t]ackiness was more expertly tucked into the glamour . . . camouflaged, so highly styled it became a kind of knowing exaltation of it until the exaltation was itself nothing but a lark.” His own persona was that of “The Impertinent Fawner.” He was not a journalist, he says, but “a writer who could carry on a conversation and shape a narrative.”

Still, he tried at times to go beyond the puff piece to “mine the ore of stardom, if not art, and find its seam and in so doing perhaps discover the very essence of that person.” The book offers examples—this time, clearly from tape recordings—of his confessional interview style, which did not include candor about his increasingly debauched lifestyle. When Daniel Radcliffe looks “a little shocked” at Sessums’ appearance following a sleepless orgiastic night, the writer claims to have been kept awake by “a stomach bug.”

I Left It on the Mountain stops far short of being a celebrity tell-all. (Sessums, now editor in chief of the upscale San Francisco magazine FourTwoNine, still needs those “heightened acquaintances.”) Instead, it is a patchwork of reminiscences organized by roles Sessums has assumed: “The Starfucker,” “The Climber,” “The Mentor,” “The Pilgrim,” “The Dogged” (about his dogs!), “The Addict,” and so on.

Addiction and spiritual struggle are the memoir’s leitmotifs. The alternately gut-wrenching and ecstatic descriptions of Sessums’ drug use and sexual binges make his ambivalence manifest. These are juxtaposed with accounts of two spiritually inspired pilgrimages, à la Cheryl Strayed—to the top of Mount Kilimanjaro and along the Camino de Santiago de Compostela.

The Kilimanjaro climb is Sessums’ belated response to his HIV diagnosis. “If I submitted my body to an experience as unforgiving as the climb up Mount Kilimanjaro,” he asks himself, “would I be able to find a way to forgive myself for the predicament I had caused by behavior far more dangerous than any mountain climb could prove to be?”

Whatever efficacy the climb has, it is temporary. His life in disarray, Sessums decides in 2009 to walk the Camino, a famous pilgrimage of more than 500 miles across northern Spain. The memoir incorporates what he describes as a diary of the trip, a vivid account of its physical hardships, moments of pleasurable companionship, and occasional epiphanies. On the trail, Sessums yearns (once again) to put aside his anger and find forgiveness; he hopes that “the brutality will live on as memory. The spiritual light will be what survives.”

But the Camino is no solution, either. Sessums cannot hang on to his sobriety. On July 4, 2010, he reaches a new low—and a new high—by injecting meth, which causes hallucinations. He paints his struggle to stay clean amid numerous relapses in grandiose terms, as a conflict involving Lucifer and various Eastern deities. “Addiction, I came to understand, is the proxy battle for the soul,” he writes. “I was in the middle of a pitched one, its violence veiled in beauty.”

Meanwhile, his downward spiral accelerates, halted periodically by the proverbial bottom: unemployment, destitution, homelessness, reliance on the uncertain kindness of friends, relatives, and strangers. For an addict, the well of favors quickly runs dry; as Sessums tells it, even his own brother reneges on a promise to send him to rehab.

I Left It on the Mountain isn’t a pretty or an especially artful book. One senses, though, that Sessums is, more than ever, writing for his life. He has always regarded that life as the stuff of narrative, he says—a way of coping with losing his parents at such a young age. “I have often thought that my impulse to write is a way to solve all the silence they left me with,” he says.

The shaping of the tale is, of course, a way of imposing control on psychic chaos. But this second memoir is itself chaotic, a jagged mosaic of thought, incident, and sensation. There is no disclaimer or apology, no suggestion that this time we are reading fiction.

*According to a spokesman for St. Martin’s Press, the legal disclaimer in the latest Picador paperback edition of “Mississippi Sissy”–referring to the book as a “work of fiction”–was a printing error.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.