Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

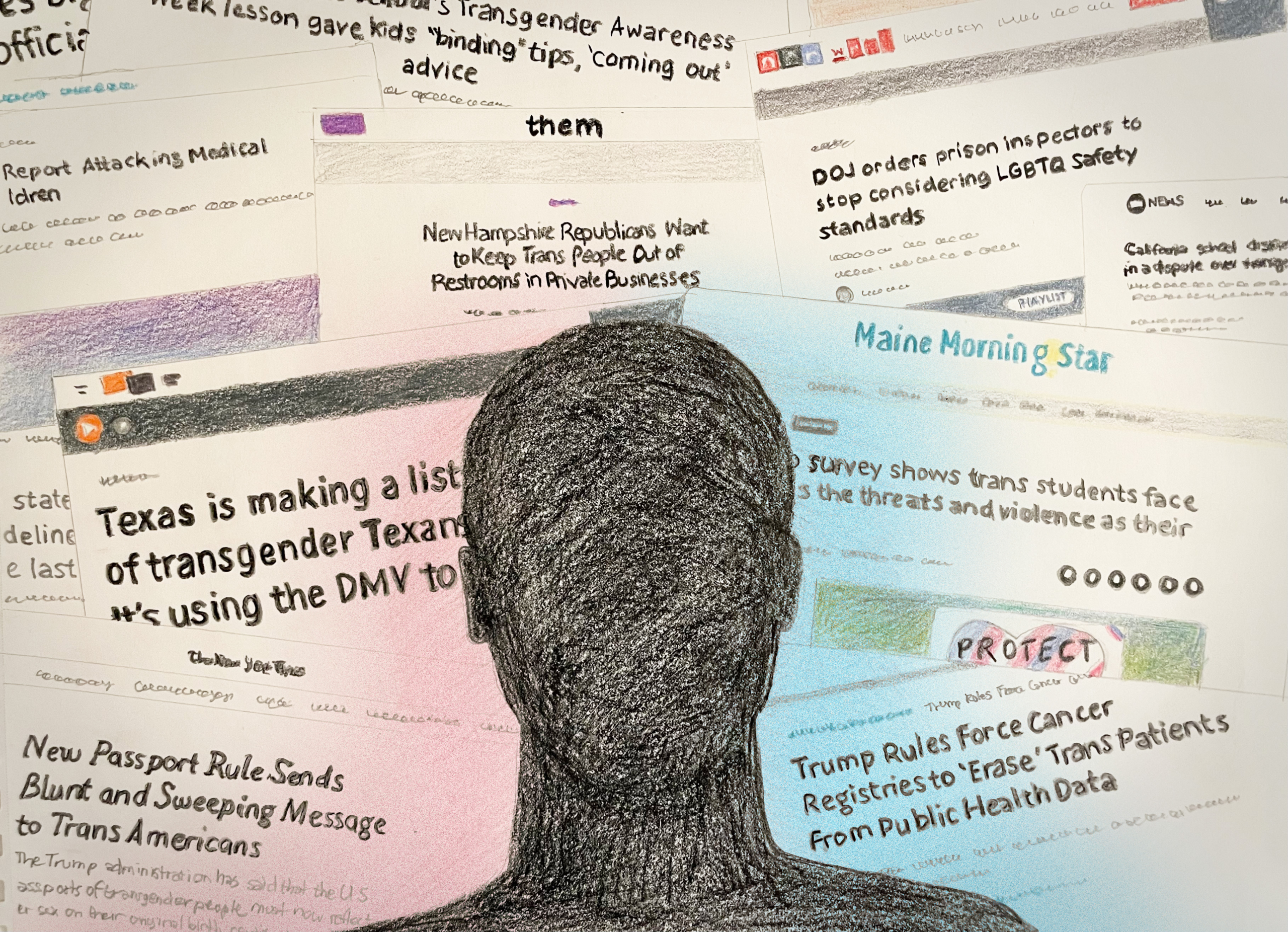

In recent years, trans people have become increasingly visible in the news. We are being banned from using bathrooms, participating in sports, serving in the military, accessing proper identification, and receiving medical care. It has always been risky to be trans, but recent political and cultural shifts against trans rights have exacerbated many of the dangers.

For trans journalists, risks tend to fall into two categories: those associated with being a trans employee and those associated with reporting as a trans person. The former poses many of the same challenges that trans people face in all fields, such as being forcibly outed by automated systems that default to legal names or having to navigate being misgendered at work. Ensuring that internal systems use preferred names is a simple way to make work safer for trans employees, as is having policies for people to report misgendering and procedures for how to respond. In the course of a series of conversations with trans journalists, one described having been misgendered by a coworker, only to be given an “accommodation” to work from home, meaning they were restricted from the collaboration and community building that take place at work. “That’s not an accommodation,” Lewis Raven Wallace, an independent journalist in North Carolina, told me. “That’s the definition of discrimination: to exclude someone from shared space that others have access to.”

Offering robust and comprehensive health insurance is also important to the safety of trans journalists. “Healthcare can help increase trans journalists’ well-being at work, and may also shield them from risks,” Nour Abi-Nakhoul, a writer and editor in Montreal, said. “Healthcare can help align a trans journalist’s appearance with their gender, which might provide some protection over the course of reporting.”

Implementing policies that create safe work environments for trans journalists is fundamental to preventing job discrimination. “ Often the reasons trans people are fired have to do with us asking for the respect, etiquette, and support that we deserve,” Wallace said. “And that becomes thinly veiled accusations of unprofessionalism, lack of objectivity, or bias.” According to the Trans Journalists Association, about half of the group’s members are freelancers.

The risks trans journalists face while reporting are harder for newsrooms to control, but important to keep in mind. Every trans journalist with whom I spoke attested to experiencing online harassment; many said they had received death threats; some have been stalked. Offering training on online harassment and social media, having protocols for tracking threats, using services such as DeleteMe, and having safety debriefs before journalists do potentially risky field reporting are all important ways to enable trans reporters to do their jobs safely. “ I want to be clear that the solution is not to restrict trans folks from reporting in the field,” Tre’vell Anderson, the executive director of the Trans Journalists Association, told me. “The solution is newsroom leadership being more intentional about the ways that they support their journalists.”

Being aware of the laws that affect your employees is also important for ensuring that journalists can do their jobs. In some states, using the “wrong” bathroom could be punishable with prison time. “Not being able to go to the bathroom on assignment safely is not just a mental-health thing, it is a physical-health and physical-safety concern,” Kae Petrin, a data journalist, said. “There’s a lot of really bad health consequences if you can’t use the bathroom when you need to.” As Anderson put it, “Bathrooms are a freedom-of-the-press issue.”

In speaking with the dozen trans journalists whose accounts follow, I found that the biggest takeaway was simply to talk to them: don’t assume what they need or restrict their reporting, keep an open dialogue about what they are comfortable doing, and create structures that offer the most protection. Their comments have been edited for length and clarity.

Erin Reed (she/her)

Independent journalist based in Washington, DC, who tracks LGBTQ+ legislation around the United States for her newsletter Erin in the MorningI do not know a transgender journalist who hasn’t faced harassment, abuse, or violent threats, and my experience is no exception. I’ve been the target of multiple swatting attempts and regularly receive threatening messages across my platforms. To navigate these risks, I rely on comprehensive digital privacy and security practices: I use a password manager, participate in opt-out programs to remove my personal information from data-broker databases, and have invested in home security measures that provide my family the peace of mind necessary for me to continue my work. Likewise, I take deliberate steps to protect my family’s privacy and share far less about my personal life on social media than I once did. Creating this separation helps maintain a necessary boundary between my work and the noise and vitriol that often accompany online spaces.

For journalists working within larger outlets, one of the most important steps is ensuring that transgender reporters are allowed to cover the subjects about which they have expertise. Many newsrooms, whether explicitly or implicitly, decline to green-light stories about transgender issues when pitched by transgender journalists. This practice sidelines critical expertise and harms coverage. It is equally important that newsrooms make real efforts to hire transgender journalists in the first place; many outlets have none on staff, despite hundreds of qualified transgender journalists actively seeking employment.

For those who are already part of a newsroom, providing robust digital privacy and security support is essential. These tools and practices are most effective when implemented proactively rather than in response to a breach. In an environment where harassment networks aggressively seek out personal information, preventing that information from leaking is far easier—and far safer—than trying to contain it after the fact.

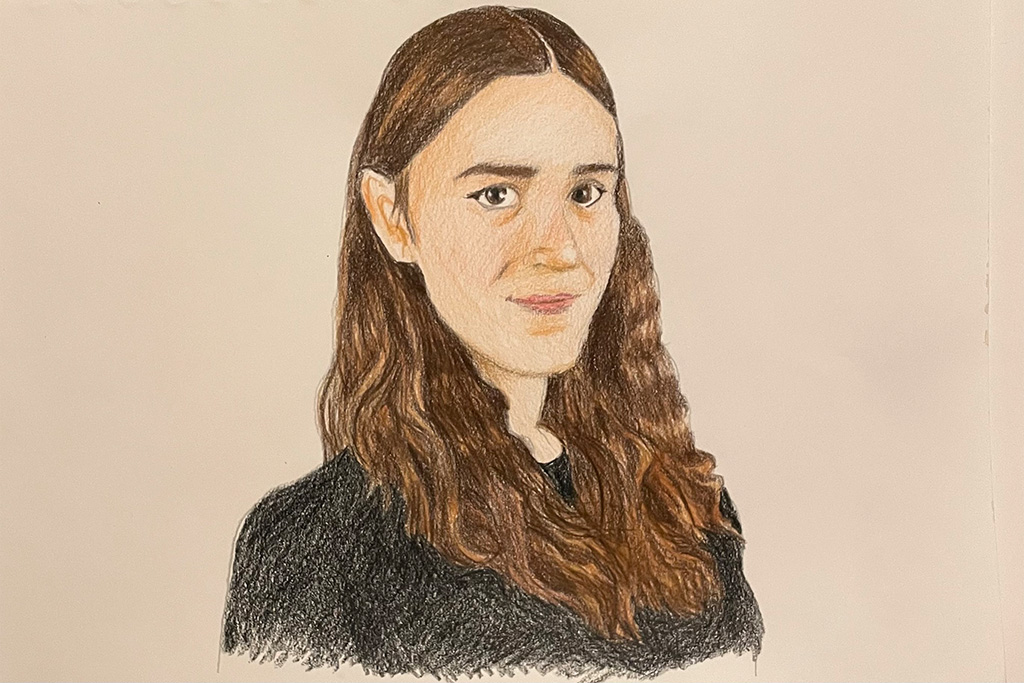

Nour Abi-Nakhoul (she/her)

Writer and editor in MontrealAs a trans journalist, I am largely stealth in the course of reporting. I do not disclose to sources that I am transgender unless relevant—for example, interviewing another trans person. This is a privilege that not all trans people have. Trans journalists might navigate the risks of being visibly trans while reporting by choosing the stories they work on carefully, and not putting themselves into situations where they would face risks, like not working as an international reporter who must travel to places with dangerous anti-LGBTQ sentiment. Trans journalists might also choose to limit their online presence or the details publicly available about them in order to mitigate harassment.

Tre’vell Anderson (they/them)

Executive director of the Trans Journalists Association, freelance culture and entertainment journalist, author, and podcast hostFor some of us, our general personhood is enough to incite ire. I was assigned to cover a protest in Los Angeles back when I was a fellow at the Los Angeles Times. There was this guy yelling about how he didn’t like the organizer. He sees me, possibly the only visibly queer person in the vicinity, and starts screaming about gay people, coming closer and closer to me. Nothing serious ended up happening, but it struck me that nobody checked in on me—not my colleague who was covering the protest with me, nor the folks back in the newsroom who were informed after the fact about what I had to go through to do my job.

While covering a different protest, I was cornered along with protesters and journalists by the LAPD when they blocked a street on both sides. They let my colleague and a number of other journalists out of the corral, but they wouldn’t let me out. My LA Times press badge was not effective. My colleague’s LA Times press badge was effective to get them out and was effective for them to get me out, but my badge wasn’t enough. Again, no one checked in on me.

What we often find in this industry is that folks believe that the way to protect and support those of us from diverse backgrounds is to push us to the side. They think they’re protecting us by not assigning us to the protest. But I wanted to be at the protest so I could be part of documenting this shift in culture that we were witnessing. I want to be there, and also I want my newsroom to check in with me after I come back. I want to be asked if I need a mental-health day because I was just verbally assaulted in public. Do I need some other kind of support or resource? Do we need to explore having security in the field for our reporters? Creating a systematic process as a leader to check in intentionally with your reporters is how we ensure that trans folks in particular still get opportunities.

These are the steps you should take to support all of your journalists, not just the trans folks. I often say that if you’re making sure that you’re developing policies that ensure the most marginalized person on your staff is taken care of, it will benefit everyone else in your newsroom.

Orion Rummler (he/him)

LGBTQ+ reporter at The 19thWhile I obviously want people to read my work, there’s this double-edged sword where if one of my stories does really well, like a lot of people are reading it or it makes it onto the Apple News homepage, then I’ll get more hate mail.

I’ve spent time on Capitol Hill in DC talking to Republican congresspeople who oppose gender-affirming care, and those are some of the most difficult conversations emotionally. I’ve never had a bad interaction with a lawmaker, but those conversations do carry risk. In the back of my head I’m thinking, “What if this story comes out and this Republican congressperson who opposes trans rights realizes that I’m trans—are they going to make a whole thing of it?” It mostly depends on their social media presence—the MAGA crowd loves to pop off on social media.

The 19th has a staff security adviser who leads emergency triage plans. If somebody gets doxed, is exposed to bad actors, or if there’s a social media hate campaign, then she’s activated.

If I’m going into a story and I think to myself, there’s a chance I’m gonna get a lot of negative attention, we have a full security briefing early in the ideation process for that story just in case. Like what do we do in this worst-case scenario? We ask what organizations might be angered by this reporting, and how might they retaliate? I’m so glad The 19th has that resource, but even if your newsroom can’t hire a security adviser, I think making editors more aware that trans reporters, even if they are not covering LGBTQ issues, are more likely to have a bull’s-eye on their back by negative actors who may feel emboldened by this political atmosphere.

Finch Walker (they/them)

Education reporter at Florida TodayHere in Florida, it’s really gotten worse over the past few years. I have to be aware of so much as I’m doing in-person reporting, like laws about what bathrooms trans people can and can’t use, and the attitudes of the general public, which can change day to day based on what’s happening in the news.

Sometimes my editor has known something could get really heated—at a school board meeting, for example—and they’ve known right off the bat that I’m at risk. And other times it’s been something I’ve had to bring up. In those situations, there’s not always an option of me not going, because we’re a really small staff. So typically what we can do is have a photographer go with me. They’re always happy to stay close to me if I feel unsafe.

There was one instance where we received death threats, so we called ahead to request that security keep an eye out and walk me to and from my car. So I think, just overall, having good communication and making sure we’re all on the same page has been really important for all of us.

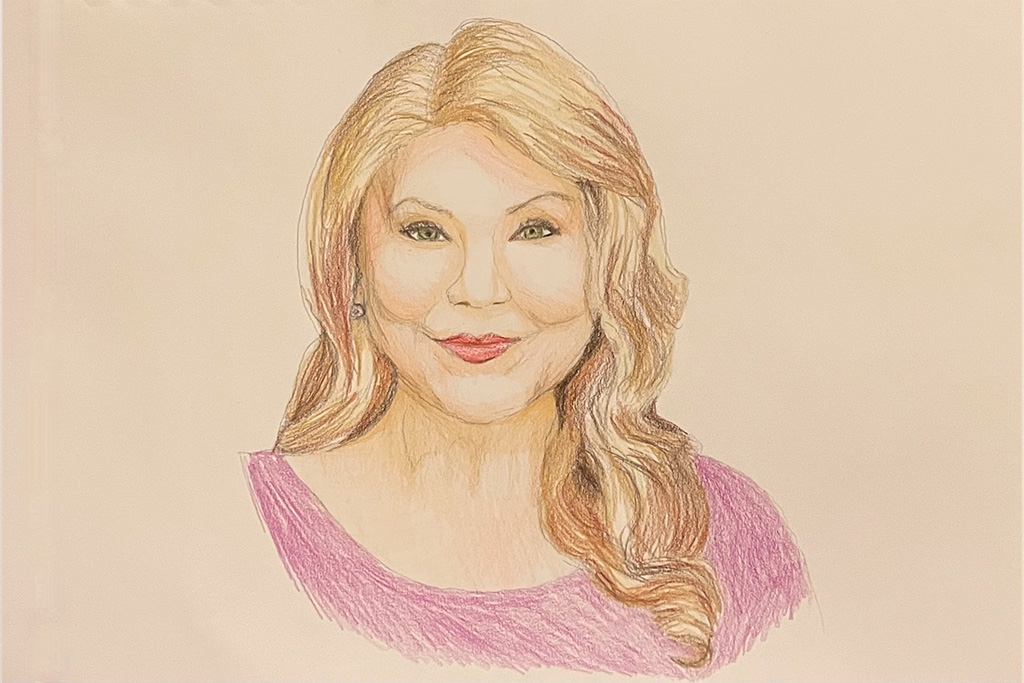

Eden Lane (she/her)

Journalist recognized as the first out transgender reporter in mainstream TV broadcasting in the US, on PBS’s In Focus with Eden LaneBeing a visibly trans TV journalist meant dealing with challenges a lot of reporters face—especially women who think about story safety differently than male colleagues do. Being in the position of having to decide whether to cover certain stories solo or go live from certain locations isn’t unique to trans journalists. But the math changes when you’re visibly trans in communities where that carries risk.

What helped me was working with assignment editors who got that my concerns weren’t complaints—they were part of doing the job safely. Just as important: newsrooms need established protocols for dealing with hostile and threatening messages before anything happens, so people are not left scrambling to figure out how to respond in the moment. That protects everyone.

The trans-specific stuff? Bathroom access during field assignments. Getting tagged as the internal expert on anything trans-related instead of just being allowed to focus on my actual beat—I’m a reporter, not a permanent consultant on transgender issues. It’s important to know your newsroom actually has your back when viewers complain about your existence. The test of real support is whether you can have these conversations honestly without it hurting your career.

Ray Hobbs (he/they)

Freelance journalist in PennsylvaniaWhen I was working in a newsroom in Philly, I worked on a vertical called Intersection where we talked about identity, disability, accessibility, queer issues, etc. The lead editor and I always felt like our section wasn’t treated the same as other sections of the paper. The top editors didn’t give us any resources or as many writers, but also nitpicked everything in our stories that they didn’t know anything about. We should care about queer people, disabled people, people who are at risk of homelessness or who are homeless. Issues affecting them are important, but they just weren’t prioritized. And as far as I know they got rid of the Intersection vertical after we left.

I think often marginalized communities don’t get reported on without Black and trans and disabled journalists, so we gravitate to reporting on our own communities, but then those are the verticals that are cut first when they need to make budget cuts.

Lewis Raven Wallace (they/ze/he)

Independent journalist based in Durham, North CarolinaNavigating public space has always been complicated for me, whether that’s public restrooms, traveling, going through the airport. My identification and my presentation don’t necessarily match, and so I’m somebody who could be arrested in a lot of states for being in the wrong bathroom. I’ve been out since the late nineties, and I don’t generally walk through the world in fear, partially because I’m a person with white privilege and a certain amount of passing privilege. But I never assume that I’m safe, especially in this escalated environment of gender profiling.

I’ve lived my whole life in places that people would consider hostile to trans people. I’m not afraid of those places, so it would be very weird for an editor to worry about me going to South Carolina, where my family is from, for example. So I think the best thing news directors and managers can do is just have really honest and frank conversations with folks about safety and ask people what they need. Sometimes people default in the wrong direction in efforts to be sensitive, either by not checking in or by overly protecting people.

Unfortunately, one of the risks that trans people face that is very complex is job discrimination, and journalism is not immune to that. Managers, editors, anybody working with a trans person needs to really look carefully at their own internalized biases and assumptions. I receive a lot of phone calls from individual trans people who have been fired on some kind of specious accusation of bias or lack of professionalism that actually has to do with their trans identity. And that’s how discrimination actually plays out: you don’t think you’re discriminating when you do that to someone, but you are.

Tat Bellamy-Walker (he/they)

Program coordinator at the International Women’s Media Foundation; on the board of the TJAWhen I was a fellow at Business Insider, I wrote this story about how my gender-affirming surgery was postponed during the COVID-19 pandemic because it was considered elective, even though for me it was lifesaving. It was a beautiful story, but it exposed me to a lot of harassment from all these blogs and online forums. I was aggressively misgendered, there was a lot of misogynoir, and I was attacked for being poor because I was on Medicaid. I wish we had done a risk assessment, because there’s a lot I wouldn’t have put in the story, but my editors were very encouraging of me using my life as a beat.

As my career went on I noticed a pattern at each new job: when I first started reporting the readers respected me and gendered me correctly, but as soon as I wrote something covering LGBTQ people, there was this really big backlash and readers started misgendering me and calling me all sorts of slurs. At one point, I even had to file a police report against someone who harassed me online and in person, because I thought she was stalking me. I got really upset because it felt like no one noticed all that I was going through.

The harassment got so bad and I felt so isolated that I took a break from writing stories to protect my mental health. After that, I had to think about what I was actually doing in this field if I’m constantly being harmed for my identity and my career isn’t moving forward because of it. I couldn’t continue to justify the abuse I was receiving, so I moved away from reporting and started working on journalists’ safety.

All that online abuse, violence, and harassment, and also in-person threats I experienced, are all tactics to self-censor journalists, to push them out of the journalism industry, especially diverse journalists or Black trans journalists like me. And that’s what it did.

I really wish editors had check-ins with me about safety, suggested trainings, or connected me to journalist-safety organizations like the International Women’s Media Foundation, PEN America, the Freedom of the Press Foundation, the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, or the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Gisselle Medina (they/them)

Immigration and religion reporter for FresnolandMy newsroom is very supportive. I’m the only trans or queer person on my team. When I took the job, I was worried about how that would go down. I’ve heard horror stories from fellow queer journalists about being harassed in the newsroom, or not being taken seriously. I had a shield up especially because I’m in Fresno, California, which is the reddest part of the state. There are a lot of progressive people who live here, but there’s still a lot of racism and homophobia.

I’ve been very upfront with both my newsroom and the sources I talk to. My pronouns are in my byline and my bio. But I’m constantly being misgendered and dealing with harassment. I’ve had conversations continually with my newsroom about how I navigate that.

I’m used to getting harassed in person and over the phone—both related to my journalism and not—and my editor has asked me to document that. But I recently had an experience at an event my newsroom was hosting. An intern we hired was talking to my partner, who’s a trans man, and she kept commenting on his appearance. When she realized we were both trans, she started interrogating me about my identity and how I could be a trans person if I never medically transitioned. It escalated to her telling us about how we couldn’t have kids and making assumptions about human anatomy. My partner and I ended up leaving the event, and later my program manager told me she’d tried to fire the intern but she resigned. Now we’re having conversations about how to fix our interview questions to emphasize that we’re a diverse newsroom. I also think we should have more than one person in interviews so there are multiple perspectives on potential hires.

Vivian McCall (she/her)

News editor at The Stranger who reports on Christian nationalism and the far rightI’ve never been targeted, but I always operate with the mindset that I could be any day. There are a lot of people who really do not like who I am and what I’m writing, and if they want to make me have a very bad day, they probably can. So I do everything I can to mitigate dangers by being pretty smart about what I post on social media. I don’t post photographs showing what’s out the window of where I live, or show the outside of my building. I don’t post about my daily schedule. I typically don’t post that I’m going to an event unless it’s my event.

It’s definitely a weird thing to balance because I’m also a professional musician. For a month, I am announcing I’m going to be here at this exact time on a stage. But you have to live, and ultimately I don’t want these people to control my life, because that’s the whole point of writing about this extremism. There’s this undemocratic grab to control the way that people exist in our society, this undemocratic impulse to deprive people of these basic tenets of American life—of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Kae Petrin (they/ze/hir)

John S. Knight Journalism Fellow at Stanford University, data and graphics reporter at Civic News Company, TJA cofounderI stopped putting my pronouns in my signature because when I was reporting in Missouri a politician screenshotted my email—not because I was trans, but just because she wanted people to know that journalists were inquiring about something she’d said—and she tweeted it out to tens of thousands of Missourians, essentially outing me to the state. Somebody probably could have figured out I was trans from Twitter or noticed in my work bio, but that was a level of unexpected scrutiny: a politician trying to make something go viral that has your phone number and pronouns in it. Now I’m pretty careful about what personal information I include in emails, especially considering that if I’m emailing a politician it might end up in a FOIA, and all sorts of people are FOIAing for all sorts of reasons these days.

I’m relatively protected because I’m a data journalist, so I’m not out in the field, but I’ve been told I should die in a fire or an oven and gotten various forms of online harassment and threatening mail.

Before giving the keynote speech at a conference in Florida, I’ve been googling the laws: Florida potentially has prison time if you’re in the bathroom of the opposite sex and you’re asked to leave, because it can be considered criminal trespassing. I’ve been trying to figure out if there will be bathrooms I can use at the university I’m going to. I was just in Malaysia, which is not very friendly to LGBTQ people, and someone led me to the women’s room. And so I went in, and someone at the sink freaked out because she didn’t think I belonged there.

If you’re sending a reporter into any situation where they could be harassed or arrested, you have a duty of care. Anytime you ask a trans person to fly for work, there are potential safety issues. I think there are certain risk factors that are unique to trans journalists or that are at least more common for us, but the bigger picture is that we should be wrapped into a robust duty-of-care policy. A lot of the things that would be written to support or protect us in the course of our job are things you should just have in your policy handbooks in general, because they are relevant to all of your employees and contractors.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.