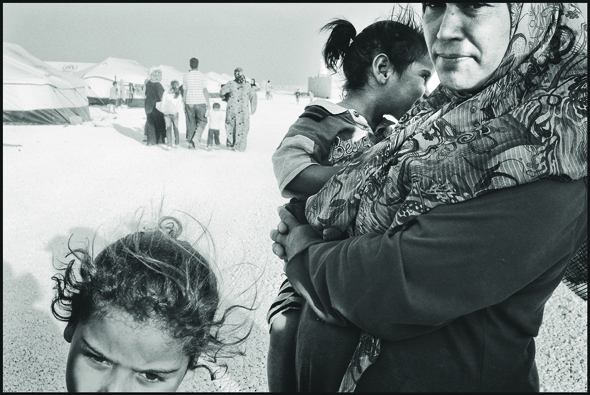

Adrift Mostly women and children occupy the Zaatari refugee camp, which sits close to the Syrian border. (Moises Saman via Magnum Photos)

When Hazm al-Mazouni shows his press pass at the entrance to the sprawling Zaatari refugee camp in the Jordanian desert, the guards don’t let him in. A 42-year-old native of Hama, Syria, Al-Mazouni’s status in Jordan is clear: refugee. But the guards are wary of his Radio al-Balad badge. “This is proof that we did something,” Al-Mazouni says, smiling. “A good thing.”

Al-Mazouni has been a refugee for 11 months and a journalist for seven. He wears brown, horn-rimmed glasses and walks briskly, a laptop bag hanging from his shoulder and two cell phones in hand, one for personal calls, the other for work. Zaatari administrators are well aware of his reporting for Syrians Among Us, a radio news program and online bulletin produced by Syrian refugees.

The program began as pilot project in October 2012 by the Community Media Network (CMN), a Jordanian nonprofit that supports independent media in the Arab world. CMN’s funding comes largely from Western foundations, notably the Open Society Foundations, UNESCO, and the National Endowment for Democracy. A US State Department grant of $77,000 paid for the first phase of Syrians Among Us.

The program is the brainchild of CMN director general Daoud Kuttab, a Palestinian-American journalist and media activist who has been working to expand press freedom in the Middle East for more than a decade. “Our goal is to give people their own voice, outside of the mainstream powers that be that control our voices,” Kuttab says.

In 2000, he started an internet radio operation called AmmanNet. From the beginning, Kuttab preferred to hire independent-minded amateurs rather than conventionally trained professionals. “I didn’t want reporters with bad habits like self-censorship,” he says. “I trained young people, critical-thinking people, who were never journalists.”

The six-month Syrians Among Us pilot project trained refugees to cover their own communities and use journalism to improve refugees’ day-to-day lives. CMN selected 33 Syrian men and women for training, with the sole criteria being prior experience in media activism. Most were revolutionaries who had been fighting against Bashar al-Assad’s regime. All were unemployed.

The trainees attended two sessions in basic journalism tactics and ethics. Hamza al-Soud, CMN’s project development manager who led some of the training, says objectivity was the hardest concept to teach. “Many of the trainees’ first stories referred to Bashar al-Assad as ‘the evil dictator’ and ‘the criminal,'” he says. They adopted more neutral language only after “some very hard discussions.”

The pilot produced 120 news broadcasts. Meanwhile, the number of Syrian refugees in Jordan increased from about 87,000 when the program began to some 520,000 in September of this year.

Western media coverage of the refugees tends to ignore the more mundane struggles of daily life. “The only news they write is numbers,” Al-Mazouni says. “How many people are killed, how many houses destroyed. They don’t talk about the refugees’ lives, their situation, their needs.” Jordanian media, not surprisingly, dwell on how Syrian refugees affect Jordan.

By early September, unemployment, rising prices, and a water shortage inside Jordan were causing tension between Jordanians and the refugees. Etaf Roudan, a co-producer of Syrians Among Us, suggested that Jordanian frustration is actually with their government’s mishandling of the situation, not with the refugees themselves. “They take money from the UN and Arab world, but they didn’t make good conditions for the Jordanians or the Syrians,” says Roudan, a native of Mafraq, which is only a few miles from the Zaatari tent city. “In Mafraq we had 47,000 Jordanians and problems with water, pollution, and employment. When Zaatari comes with 122,000 refugees, there are no jobs, no water, just disaster.”

The poorest Syrians stay in the camps because they have no choice. A recently created “bailout” system requires a Jordanian citizen’s guarantee for any refugee to legally leave Zaatari for anywhere else in the country. Without that guarantee, refugees who leave Zaatari are ineligible for Jordanian public services or UN aid. As a result, a black market in exit services has emerged, leaving those without money or connections trapped inside the camps. Official Jordanian statistics report that nearly 60,000 refugees returned to Syria from Zaatari in just one year. They’d rather grapple with Assad than remain in the camps here.

In Jordan’s urban areas, where more than 70 percent of Syrian refugees live, daily expenses are high, aid is scarce, and official work permits are even harder to find. “They give you 24 dinars [$34] for one person’s food per month,” Al-Mazouni says. “But the coupons come every two weeks. So you go twice to get them and spend at least three dinars just on transportation. Can you imagine the situation?”

Syrians Among Us tries to mitigate hostility toward Syrians. The program covers topics ranging from anti-refugee hate speech to discrimination against Syrian children in Jordanian schools. The reporters decide what topics are most pressing based on firsthand experience. Al-Mazouni, for example, visits Zaatari two or three times a week–slipping in without showing his press badge. The stories are not hard to find. “I see reports everywhere, in every face, in every corner, in every side,” Al-Mazouni says. “There are only problems there.”

One of his stories was about the hammams (bathrooms) inside the three-square-mile Zaatari camp. “There is no security inside the camp, and at night there is no light,” Al-Mazouni says. “So people are scared of going to the hammam at night.” Many refugees must walk long distances just to reach the bathroom, anyway, he says, and in the pitch black of night they are afraid of assault.

Another story he did addressed the UN’s administrative shortcomings at the Syrian-Jordanian border. The typical Syrian at the border will meet a UN worker who asks for his name and takes his documents, Al-Mazouni explained. Then he’s left without direction save for advice from other refugees. “No one tells you where to find food or water or medicine.”

A thousand people line up at the UN Refugee Agency in Amman at five o’clock every morning, Al-Mazouni says, waiting for guidance. “Everything is slow. The employees fight with the refugees. There are only six or seven workers for a thousand people. What can they do?”

Syrians Among Us works to fill this information void. Local stations in Irbid, Zarqa, Mafraq, Karak, and Ma’an rebroadcast the program, and in the next phase of the project cmn plans to distribute small radios to camp refugees so they can listen.

So far, the results of the coverage have been mixed. After his report about the bathroom situation, Al-Mazouni says, security patrols began to organize within the camp–but staffed by refugees themselves, not by the Jordanian or international administration. “Shbab [young people] from inside the camp began to make security patrols,” he says. “But they are just activists without training. They don’t really know about security. So now there are security people, but there is no security.”

CMN’s final assessment of the pilot program cites some successes. After one report on refugees in Mabrouka village, Jordanian hosts collected donations to assist the 70 Syrians living there. On another occasion, listeners organized to rescue 800 refugees who’d been left destitute in the desert.

Meanwhile, Syrians Among Us acquired $111,000 of funding from the State Department for a second phase, which began October 1 with training sessions. Broadcasts were scheduled to start in November. CMN wants to increase the radio show from thee times a week to daily, expand coverage across the country, and have at least one regular correspondent based inside Zaatari. According to Kuttab, two pillars of CMN training are truth and balance. He doesn’t expect refugees who fled Syria to be “objective” about Bashar al-Assad, but their stories must not exaggerate and must include other points of view. “You can be subjective, but still fair,” Kuttab says.

The program is not about agitation or opinion, Al-Mazouni adds, but about news: “My emotions are my own. When I write something, I must reflect the reality.”

Asked if he’ll continue with journalism if the Syrian war ends, Al-Mazouni interrupts. “Not war, revolution,” he says. “And when it ends, not if. Of course it will end; we will return and we’ll build our country.”

Will he build as a journalist, an activist, or a businessman? “All. Anything. Everything,” Al-Mazouni says. “I’ll do everything for my country.”

Alice Su is a freelance journalist based in Beijing, China, formerly in Amman, Jordan. Follow her on Twitter @aliceysu.