Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Back in 1999—simpler times, perhaps—there was a little-noticed brouhaha in federal court over an effort to get several secret US government documents released through official channels. The James Madison Project, a Washington-based nonprofit that champions openness and accountability in government, especially on national security and intelligence matters, was sparring with the Central Intelligence Agency. At issue were what are believed to be the six oldest classified documents held by the National Archives and Records Administration—memoranda created around 1918 describing methods for making and detecting the “secret ink” used by the German imperial government for espionage during the Great War.

The proceedings were respectful, which is typical of most litigation under the Freedom of Information Act, a law passed by Congress in 1966 to promote greater public knowledge of government decisions and actions. The plaintiffs pointed out that the details of America’s first encounter with the use of secret ink as spycraft had been revealed in a book published in 1931 by a disgruntled former State Department official who was a codebreaker during World War I. But the CIA, which did not exist at the time the memoranda were written yet came to control their distribution, was adamant: the documents could not be declassified, eight decades later, because the information would make its current covert communications systems “more vulnerable to detection…by hostile intelligence services or terrorist organizations.” In light of legal precedent requiring deference to the views of government national-security agencies in FOIA lawsuits, the judge in the case declined to order the documents declassified.

Twelve years on, the secret ink documents and others from the era stashed away in the Archives—now more than ninety years old—are still under review for declassification.

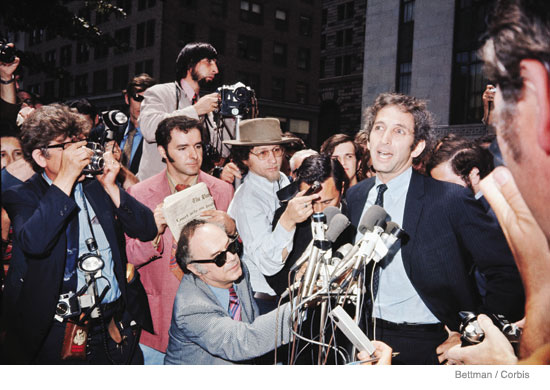

The New York Times, then The Washington Post and elsewhere, revealing a sorry bipartisan history of lies and deception. This resulted in an epic court battle between the government and the press and, beginning a year later, the wild and unpredictable criminal trial—under the Espionage Act, among other statutes—of the main protagonist, former Pentagon official Daniel Ellsberg, who had leaked the Papers. The Nixon administration was caught unawares by the revelations in the Papers, and went on an unseemly chase to figure out what the documents were, where they had come from, and how to control the presumed damage from their release. The panic was particularly poignant at the time because then-Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger was engaged in secret negotiations to open a relationship between the United States and the People’s Republic of China; he feared that Mao Zedong and Chou En-lai would suspend talks with a government that couldn’t keep delicate matters confidential. He persuaded Nixon and his attorney general, John N. Mitchell, to go to court against the newspapers and seek a prior restraint on further publication. Kissinger, incredibly, dubbed Ellsberg “the most dangerous man in America” (the convenient title of a 2010 Oscar-nominated biopic that has been given new relevance, and more widespread screenings, by the WikiLeaks affair). The pretext, of course, was national security—that continued exposure of details from a study officially classified “top secret” would do irreparable harm to the United States and its forces in Southeast Asia. Never mind that the Times had locked up an elite group of reporters and editors in a hotel suite for months to review the documents and compare what was already on the public record, in order to determine what was notable and worthy of public attention without putting the country or its troops at risk. In the context of an increasingly bitter atmosphere between Nixon and his critics—Vice President Spiro Agnew was routinely drawing cheers at the time with his attacks on the “nattering nabobs of negativism,” and reporters were being hauled before grand juries and told to reveal their sources about the Black Panther Party and other controversial topics or risk imprisonment—there were political points to be scored by pursuing the newspapers. The pursuit was intense and, with the benefit of hindsight, sometimes absurd. During one closed hearing in US District Court in Washington, when the late Judge Gerhard Gesell was to determine what in the Papers might be dangerous if revealed, representatives of Nixon’s Justice Department insisted that the courtroom doors be locked and brown paper taped over their small windows, lest the reporters lurking in the hallway be able to learn new secrets by looking in and reading lips. Appellate court deliberations went into the night, and presses were stopped awaiting the outcome. For all its months in court, the government was never able to prove the slightest harm to national security as a result of the Pentagon Papers’ disclosure. On the contrary, it is clear that the publication of the Pentagon Papers was immensely valuable as a contribution to the public dialogue about the Vietnam War. It did not end the conflict overnight, as Ellsberg might have hoped, but it certainly made opposition to it more acceptable and understandable. History, Off Limits It would be encouraging to believe that the government has learned important lessons from the Pentagon Papers case and other, less celebrated ones since then. But in fact the problem of secrecy and the inappropriate classification of information valuable to the public has grown dramatically in recent decades. Although the Archives routinely conducts a review of classified documents to evaluate whether they are eligible for release, its current backlog runs to some 417 million pages, mostly dating from the 1940s through the 1970s. It will only grow, given the natural human tendency for government bureaucrats to believe that if their work is important, it must be confidential (or secret, or top secret, or on up the line into “code-word clearances” whose existence is itself classified). At its best, the declassification process is quite cumbersome, with representatives of various agencies entitled to weigh in and block release of material that may not have caused concern in the agency where it originated. Thus, the gaping holes in some volumes of the official Foreign Relations of the United States issued by the State Department. But it is the influx of new material in electronic form that has officials at the Archives reeling. According to Jason Baron, its director of litigation, there were 32 million e-mails transferred to the Archives from the Clinton administration, and the final number from the presidency of George W. Bush is expected to be about 250 million. “At the present rate of e-mail creation,” says Baron, the Archives “expects to receive over one billion e-mails over the course of the next decade as permanently accessioned records of the government.” If all of those had to be reviewed for potential release under FOIA, he estimates, it would take a hundred people, working ten-hour days 365 days a year, fifty-four years to complete the task. Even the recent creation of a National Declassification Center within the Archives has not inspired optimism about solving the disastrous problem of classification run amok. With one intelligence agency alone creating a petabyte (a million gigabytes, or the equivalent of 49 million cubic feet of paper) of new classified records every eighteen months, the US Public Interest Declassification Board, an obscure panel created under the inspiration of the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, the New York Democrat, to advise the president on these matters (of which the author is a member), has recently been entertaining potential schemes for “mass declassification.” At a public board hearing last September, Jeff Jonas, chief scientist of IBM Entity Analytics based in Las Vegas, asserted that the volume of classified documents may well be “beyond human, brute force review,” and he appealed for the introduction of “some form of machine triage” into the declassification process. Jonas promoted the concept of “context accumulation,” whereby computers would review classified documents and would, over time, gain increasing sophistication—with decreasing amounts of human input—about which truly need to be protected. The threshold challenge would be to persuade federal agencies, especially the many involved in intelligence work, to trust such a bold new process; the hope would be that once it took effect, the pace of classification and the number of classified documents would eventually decrease, and thus potentially compromising leaks would become less likely and, some would argue, less necessary. Informed Consent Meanwhile, until the new era dawns, the WikiLeaks case provides everyone an additional opportunity to live with the old. On the substance of the diplomatic cables that were distributed, it was difficult to claim damage to American national security. It may be awkward, say, for Saudi Arabia and certain other Middle Eastern states to have it known that they are every bit as worried about Iran as are Israel and the United States, if not more so, as revealed through WikiLeaks, but hardly a threat to anyone’s well-being. And for the Chinese to be identified as complaining that North Korea was behaving like a “spoiled child” is not terribly surprising. “The members of the Foreign Service owe a great debt to Julian Assange,” observed Charles Peters in the Washington Monthly. “He got their cables read.” And Fareed Zakaria, writing in Time, said the published cables were “actually quite reassuring about the way Washington—or at least the State Department—works.” Indeed, leaked cables revealing foreign-service officers’ assessment of the precarious hold on power of the corrupt regime in Tunisia, just weeks before it fell, looked positively prescient. In the end, it may have been the unpredictability and loss of control in the WikiLeaks case that most rattled the bureaucracy. Although the government lost both its civil and criminal cases involving the Pentagon Papers, it is remarkable in retrospect to what extent it managed to control the process at the time. In both New York and Washington, federal courts halted publication of the documents for almost two weeks—in effect granting a prior restraint on the free press—while government lawyers attempted to prove that grievous harm to national security was at stake. The US government has seemed bewildered—helpless, really—in the face of the WikiLeaks disclosures. To seek even a temporary halt in publication by The New York Times would have been pointless, since other organizations outside the reach of the US judicial system could easily pick up the slack. Whereas it took a photocopying session followed by a plane trip to keep the Pentagon Papers moving from one newspaper to another, WikiLeaks could stay ahead of the game with just a few keystrokes on a computer. The WikiLeaks disclosures draw attention to an important lesson: the old-fashioned notion that democracy cannot function effectively without the informed consent of the governed, which requires timely access to accurate information across a broad spectrum of official activity. That access is more threatened than ever, as the mountain of needlessly classified government documents grows daily, and the result is to increase public suspicion and weaken government’s credibility. As a commission chaired by Moynihan said in its 1997 report, “[t]he best way to ensure that secrecy is respected, and that the most important secrets remain secret, is for secrecy to be returned to its limited but necessary role. Secrets can be protected more effectively if secrecy is reduced overall.” On the surface, President Obama urged greater transparency in government when he came into office, and at the end of 2009, he issued an Executive Order requiring outside review of agencies’ classification guidelines and forcing those who create classified documents to identify themselves openly. But because the order allows top officials to delegate those decisions to an unlimited number of subordinates, it may make government even more opaque. Ironically, Manning’s alleged massive dump of documents to WikiLeaks seems to have resulted from a post-9/11 “reform” introducing greater sharing of material among agencies in an attempt to prevent terrorism. Good intentions and noble rhetoric notwithstanding, Obama officials have gone after more alleged leakers of government secrets than any other recent administration. Since World War II, there have been only ten criminal indictments brought under the Espionage Act for the unauthorized disclosure of classified information; half of them were initiated during the still-young Obama presidency. The likelihood of success in such cases is low—only one of those indicted has been convicted, so far—but the prospect of intimidation and suppression of public debate is high. Only cynicism can result. Those who would create greater respect for the sanctity of properly classified information would do well to heed the words of the late Erwin N. Griswold, former solicitor general of the United States, in a February 1989 Washington Post op-ed column in which he recanted, nearly eighteen years after he had tried, on Nixon’s behalf, to prevent the continued publication of the Pentagon Papers: It quickly becomes apparent to any person who has considerable experience with classified material that there is massive overclassification and that the principal concern of the classifiers is not with national security, but rather with governmental embarrassment of one sort or another. There may be some basis for short-term classification while plans are being made, or negotiations are going on, but apart from details of weapons systems, there is very rarely any real risk to current national security from the publication of facts relating to transactions in the past, even the fairly recent past.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.