Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

This week, countless American journalists have been weighing the costs of joining the Women’s March in Washington, DC, or one of the many sister demonstrations being held on January 21.

Staffers coast to coast, from The San Francisco Chronicle to The New York Times, have received specific edicts against attending. Others likely know the tried-and-true rule, handed down from standard-setting organizations like The Associated Press: Journalists are not allowed to join protests or demonstrations, in order to avoid appearance of bias. According to the AP’s guidelines, staffers “must refrain from declaring their views on contentious public issues in any public forum…and must not take part in demonstrations in support of causes or movements.”

The longstanding and rarely questioned rule was designed to protect the credibility of reporters and their news organizations, and to many, it looks like common sense. But it has arguably become just another barrier to entry in an industry already struggling with a pronounced lack of diversity.

I abided by this rule for as long as I worked in newsrooms that enforced it (and am only able to publicly question it now that I’ve left). I felt I hardly had a choice; it was a matter of working or not. I learned the rule (and many valuable journalism lessons) from a respected elder of my field, who also happened to be a white man. He cut his teeth in New York City tabloid newsrooms, those long-gone, smoke-filled lairs of hard-drinking men where teletypes and ringing phones never stopped their clamor, and women and people of color were few and far between. My educator was very likely taught the rule by another white man. The rule echoed through newsrooms generation after generation until it reached me, an Iranian-American woman.

I will march not just because I understand inequality to be real and would like to live to see its end, but also because I’m deeply grateful for my right as an American to peaceful protest, and I intend to use it to call for a basic tenet of journalism: fairness.

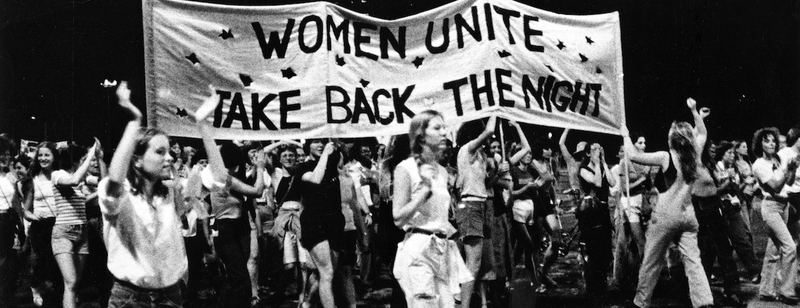

It’s time to recognize the effects of this harmful rule and rewrite it. I don’t know yet if I’ll carry a sign or flowers, but I will travel to Washington to march this weekend in the tradition of every generation of women before me, because we have faced gender inequality for as long as historical record serves. Gender inequality persists today in countless demonstrable ways. I will march not just because I understand inequality to be real and would like to live to see its end, but also because I’m deeply grateful for my right as an American to peaceful protest, and I intend to use it to call for a basic tenet of journalism: fairness.

Demanding equality is a core tenet of journalism, a fundamental belief of many of its practitioners, and should no longer be sidelined. In an era when public trust in the media has hit a historic low and our work and its ethical underpinnings are questioned at every turn, America needs to get to know journalists as I know them: We are not perfect. Sometimes we are too obedient, too slow to query, too easy to distract. But we are by and large ethical and fair-minded people tasked with a job that gets harder all the time. Our identities are not a bias. Women who want equality aren’t biased. They are fair.

This matters to me in part because I was the first Iranian-American to walk into most of the newsrooms where I worked. As the daughter of immigrants, I dreamed of becoming a Tehran correspondent someday. A generation of other Iranian-American journalists, like Maziar Bahari of Newsweek and Jason Rezaian of The Washington Post, achieved that dream, only to land in Iranian prisons.

We must respond by habitually demonstrating that our aims are noble, and operate with a more realistic version of transparency, one that allows diverse journalists to be themselves.

I rededicated myself to American journalism, and now the situation is growing increasingly precarious at home. The Obama administration’s actions against the Times’s James Risen have made our industry more vulnerable to abuses of power. Leaders who vilify journalists, as soon-to-be President Donald Trump habitually does, can mean disastrous things for press freedom. We must respond by habitually demonstrating that our aims are noble, and operate with a more realistic version of transparency, one that allows diverse journalists to be themselves.

My personal reasons may be unique, but I believe plenty of white male journalists’ commitment to equality runs just as deep as that of many reporters, photographers, videographers, and editors who happen to be people of color, women, or queer. This era promises to bring more challenges for diverse journalists, who have been harassed and targeted by Trump himself and by the rabid internet trolls who often back him. It’s our responsibility to support our most vulnerable colleagues.

It is time consider a new slate of rules by which journalists can responsibly engage in civic and civil dialogue in a manner that exemplifies their dedication to service. Newsrooms can come up with fresher rules or counsel discretion on a case-by-case basis for their staff. Bosses can mandate that reporters declare their activism in advance, or ask staffers not to carry signs. Perhaps journalists can develop signs that carry messages based on the tenets of our craft: Support Government Transparency, Equality for All, Let Freedom Ring, or (for the especially brave) Tell Me Your Story, I’m a Reporter and I Care.

Protest matters because it can push back effectively against a president who is stoking authoritarianism. Trump has repeatedly used his bully pulpit to disparage the press, dubbing entire news organizations “fake news” and painting journalists as elite and out-of-touch. A meek response to Trump’s bullying approach to public relations means he will continue to define the narrative, and the image of journalists everywhere will suffer. We know that his accusations of bias are not based on actual bias, but on the persistence of headlines that don’t serve his interests. It seems like a good time to remind the country about American journalism’s intentions. Dissent and questioning authority should be second nature to any good journalist. We did not sign up to be stenographers for ruling elites, corporate interests, or smug celebrities.

Like many journalists, I have covered countless protests. When civil rights protesters marched deep into a hollow in the West Virginia hills to hold a candlelight vigil for a mentally disabled black woman who had been held captive and abused by six white men and women in 2007, I stood alongside them and took notes by flickering candlelight.

I dodged the eggs hurled at demonstrators from high-rise apartments lining Wilshire Boulevard in Westwood during a march in the wake of the passage of Proposition 8 in California. The 2008 vote had stunned LA’s LGBT community by banning gay marriage, and while marchers flicked bits of eggshell from their clothes, I gathered reactions and called in quotes to the desk. When Occupy encampments at Los Angeles City Hall were dismantled in the middle of the night in 2011, I was there—for a time, obediently cordoned off in a media pen with the other grumpy reporters.

Dissent and questioning authority should be second nature to any good journalist. We did not sign up to be stenographers for ruling elites, corporate interests, or smug celebrities.

I’ve also taken part in many demonstrations, but never while employed as a reporter. When Iranians took to the streets of Washington, DC, to protest American support for the Shah in the summer of 1978, I was there—still in the womb. Growing up in Southern California, I frequently joined protests calling to end wars or to free political prisoners. My first month as a journalism graduate student at New York University, I attended a vigil marking the first anniversary of 9/11, standing wet-faced alongside hundreds of others who remembered that day and prayed for peace together in Union Square. That same year, with the Iraq war looming, I spent several weekends riding the bus to Washington, DC. I feared wars in Iraq and Afghanistan would bring endless chaos to the Middle East and South Asia. At the marches, I took photographs and avoided chanting—obedient to rules that didn’t yet fully apply to me.

It’s worth noting that protests are not riots. They tend to involve speeches, signs, some chanting, and some walking. In the act of protest, there is catharsis and beauty. The swirl of people all around you, all stepping in the same direction: forward, forward, ever forward. Protests around the world are met with police brutality, abductions, and sometimes death, but I’ve never so much as skinned a knee.

Many journalists view their vocations as their identities, deciding that they can apply a lack of bias to all their interactions. They might abstain from registering with a political party, or ever casting a ballot. But there are many others who would join a protest to demonstrate for equality, if only they could.

As a woman of color, I have been told to set aside my identity—no easy task, and patently dishonest—and my desire for equality so that I can report like a robot facsimile of a supposedly pure standard. But any journalist’s excellence depends on much more than that. We are told to speak truth to power, to reveal inequality, to empower the disadvantaged and the poor. But diverse employees are also told to stay silent where they feel their own rights and those of other marginalized communities are threatened. Perhaps that’s part of why, despite decades of efforts, newsroom diversity is actually declining in some sectors.

Looking back, I wonder: What did those white men who wrote the rule against speaking out have to protest, as newsroom leaders in a system set up to perpetuate their advantage? What were they, perhaps unwittingly, asking a more diverse future workforce to give up as a precondition to joining the industry? Newsrooms can’t selectively pretend away the diversity within their ranks when they feel it doesn’t serve them, only clinging to it when it produces better access and more richly reported stories from within minority communities. I fear the message such a rule really sends is: Welcome into our newsrooms, all you wonderfully diverse reporters and editors. Could you please leave your pesky identities and demands for fairness at the door?

That last part is troubling; if media discovered the Trump administration were to systematically pay women or minorities less, it would be front-page news. But that sort of disparity exists in most American newsrooms, even at top publications such as Dow Jones.

On a women’s journalism Facebook group recently, I saw a journalism student’s post asking if participating in the Women’s March might hurt her chances of future employment.

The responses startled me. Some newsroom veterans told her they would never hire a woman who had publicly demonstrated for equal rights. Others considered her student status a loophole, and said she could attend. Yet others suggested well-meant methods of getting around the rule: Write about it for your local publication. Or go, but avoid cameras and social media. I was alarmed that professional journalists would tell a young woman to engage in such subterfuge, just to call for equal rights.

More than ever, we should stand for the basic principles of why we tell stories. We tell stories to preserve the rights and dignity of others. We must stand for something.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.