Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

News organizations have spent the past few years strategizing around climate change, the story of our time. Those conversations have resulted in an uptick of coverage—from major investigations to explainers to conferences such as the one CJR will host on April 30. It is clear that, as an industry, we are trying to do our part in informing the public about the trouble that awaits.

But when it comes to writing about the harm humans do to the environment, our conversations have rarely turned inward. Last year, Low-tech Magazine, a tech skeptical outlet run by Kris De Decker, took the plunge, paring down its web presence with the environment in mind. Low-tech’s ethos discourages belief in the theory that all technological advances are positive ones. A few months ago, the outlet published a story about how to heat a home with a mechanical windmill; a feature that ran in February 2017 focuses on Vietnam’s decentralized, low-energy food system, which produces little waste. The magazine publishes infrequently; in 2018, nine stories were published. So far this year, just two have been posted.

De Decker, who previously worked as a technology reporter, started the magazine in 2007. Electric Eel, a newsletter about storytelling, recently wrote about the outlet.

“For 10 years I interviewed engineers and scientists about new technologies and renewable energies. And I kind of learned during that period that, well, it doesn’t really work,” De Decker tells CJR from his home in Barcelona. Around the same time, De Decker stopped flying, opting instead to travel by train, boat, or bike. Readers would sometimes remark that while the magazine preached an ethos of low-tech, it still relied on the most prominent of high tech inventions: the internet.

“Of course, that’s the only option I have because that’s where readers are. But at the same time they had a point. And when, two years ago, I got an offer from two interns from the United States to redesign the website, I thought this is a moment to try to practice what I preach in the medium itself,” De Decker says.

RELATED: A new digital magazine forces you to unplug from the internet

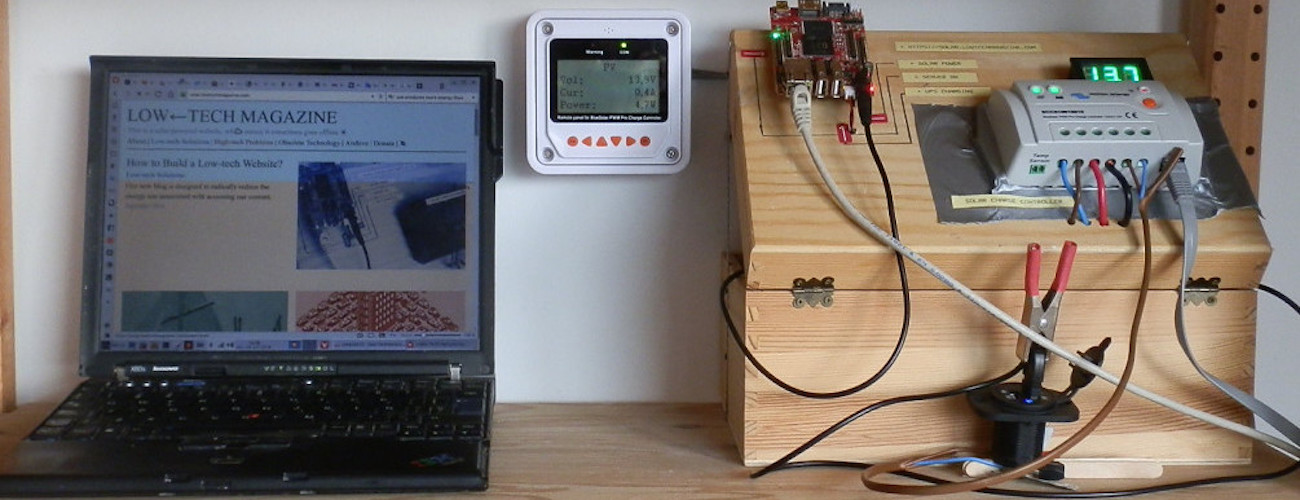

Last year, De Decker launched a self-hosted, solar-powered version of the magazine’s website in an attempt to reduce the amount of energy needed to run it. This version of Low-tech Magazine is static—every visitor sees the same thing. Most modern websites are dynamic, meaning they are constantly changing and in constant need of energy. To help reduce the amount of energy needed to keep the website running, De Decker opted for basic typefaces and “dithered” photos. This also makes the site easier to access on old computers or slower internet speeds.

The website itself runs on an Olimex A20 server, a small computer with just 16GB of storage. The server requires between one and two watts of power depending on the number of people visiting the magazine’s website at any given point; this power is supplied by a Li-po battery that is charged by a 50-watt solar panel De Decker stores on his balcony at home in Barcelona. When the weather is bad, the solar-powered battery doesn’t charge, and the website goes down. This is intentional. (There are two additional lead-acid batteries that will keep the site running for up to 48 hours in case of prolonged periods of dark weather, during which the solar panel won’t charge the Li-po battery. Readers can also buy a book, printed on demand to avoid unnecessary paper usage, featuring all the articles on the website.)

One way De Decker limits the energy output of his magazine is to consider the size of every individual page on his website. On the dynamic version of the website, the page hosting an article about energy security is 2.7 MB. The same story on the solar-powered one is just 329 KB. By comparison, this text heavy New York Times article about the Mueller report is 5.1MB. The page hosting this NYT video about blackouts in Venezuela is 8MB; when fully loaded, this NYT documentary about train delays, just under 11 minutes, is about 185MB. This text-based Washington Post story about Facebook is 14.4MB. A Los Angeles Times story about a mural is 3.8MB.

The internet on which we publish our stories and videos and live-streamed news shows, thought of in our collective consciousness as intangible, is anything but, De Decker emphasizes.

“Until now, we have not really realized that the internet uses energy. We have this idea that it’s all in a cloud, and weightless, and people don’t really think about it when they publish something,” De Decker says. But it comes with a cost: servers that exist in real life require constant cooling to make our jobs possible and the electricity needed to power the devices our readers consume our work on needs consideration, too.

Because the internet evolved—and is evolving—so rapidly, it’s difficult to collect data in the aggregate about its environmental impact—and about the extent to which news organizations in particular contribute to the energy output. In 2009, the Christian Science Monitor reported that 2 percent of human carbon dioxide emissions are produced by the internet’s infrastructure—a level on par with the aviation industry. Tech companies like Facebook, on which we rely to distribute stories and connect with readers, are planning to build their own broadband cables on the floor of the ocean, to enable more people to use the social network, and for cheaper. Google owns 63,605 miles of its own underwater cables. Meanwhile, Amazon, whose founder owns The Washington Post, has plans to shoot satellites into space to better internet connectivity. The NYT is experimenting with 5G technology.

Streaming video services like YouTube and Netflix—both companies news organizations have partnered with—account for the biggest chunk of internet traffic, and a Greenpeace report found that the energy sources these and other video streaming services use are often not renewable. And things like autoplay on videos at news sites are a burden on older computers and slower internet connections, and ought to be scrutinized for their utility, De Decker adds.

A website built in the spirit of the past isn’t just environmentally friendly, De Decker suggests. It’s a good way to compete for readers whose attention spans online are increasingly fickle, a challenge to the idea that attention can only be caught by the shiniest objects.

“Many web managers try to catch the attention [of readers] by using lots of flashy things and streaming stuff, but what we noticed is that by doing the opposite, you get a lot of attention too,” he says. “The site is not just using very little energy but it’s also very comfortable to use. The pages download extremely fast, it’s easy to find things. It’s not just about energy use, you make sites very user-friendly.”

The scale of a news organization like the Post or the Times is, of course, dramatically bigger than Low-tech. De Decker writes every article for the magazine, which feature images but no videos, and he worked with a small team to build the solar-powered website. De Decker acknowledges that a similar effort at a bigger outlet posting upwards of a hundred articles a day would be very complicated, but believes the effort is worth it.

And there’s another hidden upside: slower news would curb disinformation. As Notre Dame burned, on April 15, and the world tuned in, De Decker was reminded of the ease with which misinformation spreads online during breaking news situations.

“What do we lose if we read about it tomorrow morning and we get all the details when all the details of the story are known,” De Decker says, “instead of losing our time listening to, ‘it could be that or it could be this’ and all kind of wild theories that in the end don’t turn out to be correct.”

As journalists continue to push the bounds of storytelling, we have a responsibility to consider the cost at which such innovations come. De Decker says that old technology deserves our consideration, but a less radical approach can help too. De Decker challenges journalists to consider, for example, whether all our videos need to be published at maximum pixel capacity.

“Maybe you can do it with less. If you upload an image, maybe compress it first,” De Decker says. “I think there’s a lot that can happen with small changes.”

ICYMI: A battered New York press and the hope of The City

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.