Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

The release of the 2018 Associated Press Stylebook is an appropriate time to look at how these guidebooks have changed over the years, and how they have also stayed the same.

The new AP Stylebook, the largest yet at 638 pages, includes “about 200 new or revised entries, with chapters covering business, fashion, food, religion and sports terms, as well as media law, news values, punctuation, social media use and a new polls and surveys chapter,” the website says.

RELATED: New AP Stylebook guidelines, influenced by #MeToo, hurricanes, and online polls

The AP Stylebook is a Web-based subscription service that’s updated frequently and has a useful Ask the Editor feature. We’ve already discussed a few of the changes, including those spurred by recent events and at least one spurred by users’ complaints.

But some journalists still prefer the paper version: For many, having the AP Stylebook near to hand feels imperative.

That was true for this columnist, whose first copy, the 1970 edition, is dog-eared and coffee-stained, with exceptions rubber-cemented or penciled in through three college addresses and two professional ones. It is 52 pages long, organized by topics like capitalization, spelling, markets, and sports.

Nine pages of the 1970 edition are taken up with requirements for “Teletypesetter Copy” (“All material must be transmitted in justified lines”) and “Filing Practices” (“Pre-punching in tape either a flash or a bulletin in anticipation of a major story is strictly forbidden”).

In fact, most stylebooks began as typesetting or technical manuals, attempts to assure consistency in print or, in the AP’s case, transmission. The AP Corporate Archives, which documents the organization from its origin in 1846, includes a treasure trove of stylebooks and related guides dating to 1900, and the archives staff has shared them with us. These guidelines were not even called a “stylebook” until 1953.

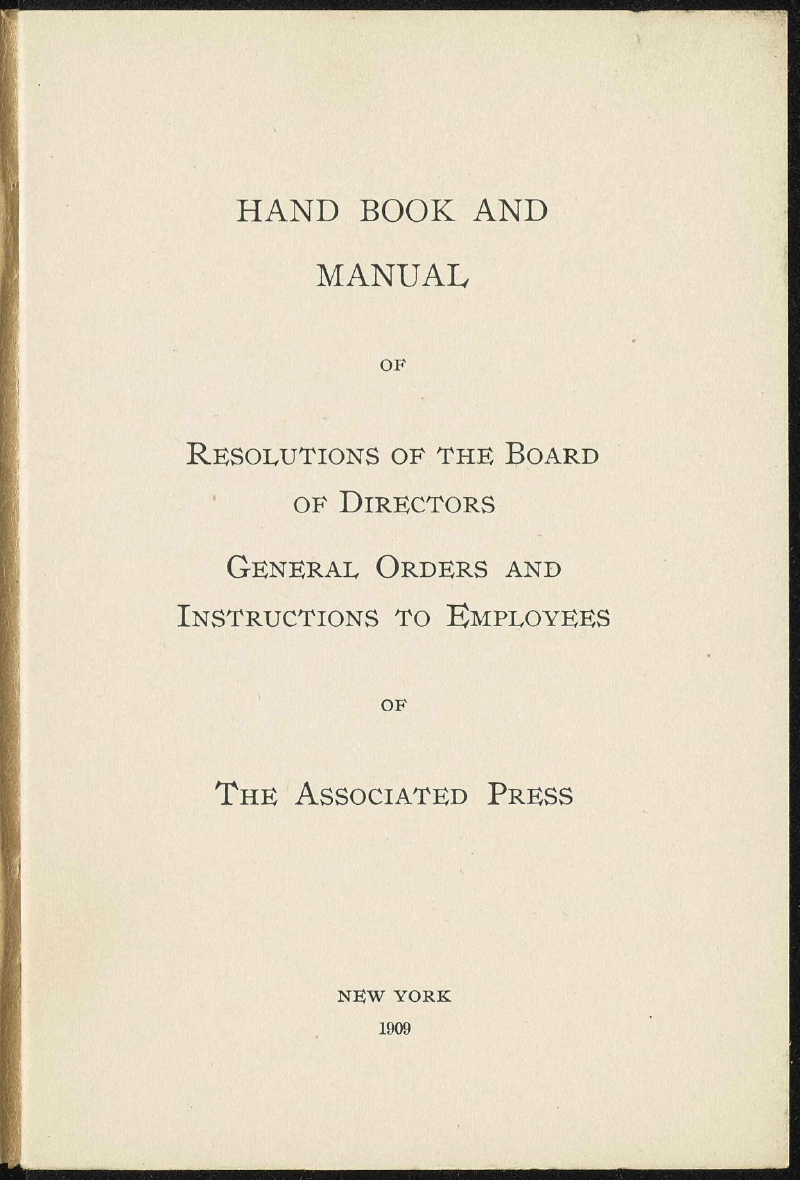

The first one dealing with words to any extent was in 1909, with a mouthful title: Hand Book and Manual of Resolutions of the Board of Directors/General Orders and Instructions to Employees of The Associated Press.

That 1909 manual has “rules” in no particular order. Some sound familiar, like No. 204: “Correspondents should at all times be diligent in getting news on the wires at the earliest possible moment,” though that one was because, with so many morning and afternoon papers in the US, “it is always likely to be available for immediate publication at some point.” Some are quaint, as in No. 307: “The use of the word ‘phone’ for telephone, or ‘phoned’ for telephoned and similar abbreviations, are prohibited in The Associated Press.”

There’s even some basic journalism: “The first paragraph of every story should contain the gist of the news. This rule is imperative.” The reason is not just to deliver quick comprehension; it “insures the transmission of the facts in case the wires are interrupted after a story has been started.” And thus we have the inverted pyramid form of writing.

But most of that 1909 guide still focuses on the mechanics of transmitting stories in the age of radio and telegraph.

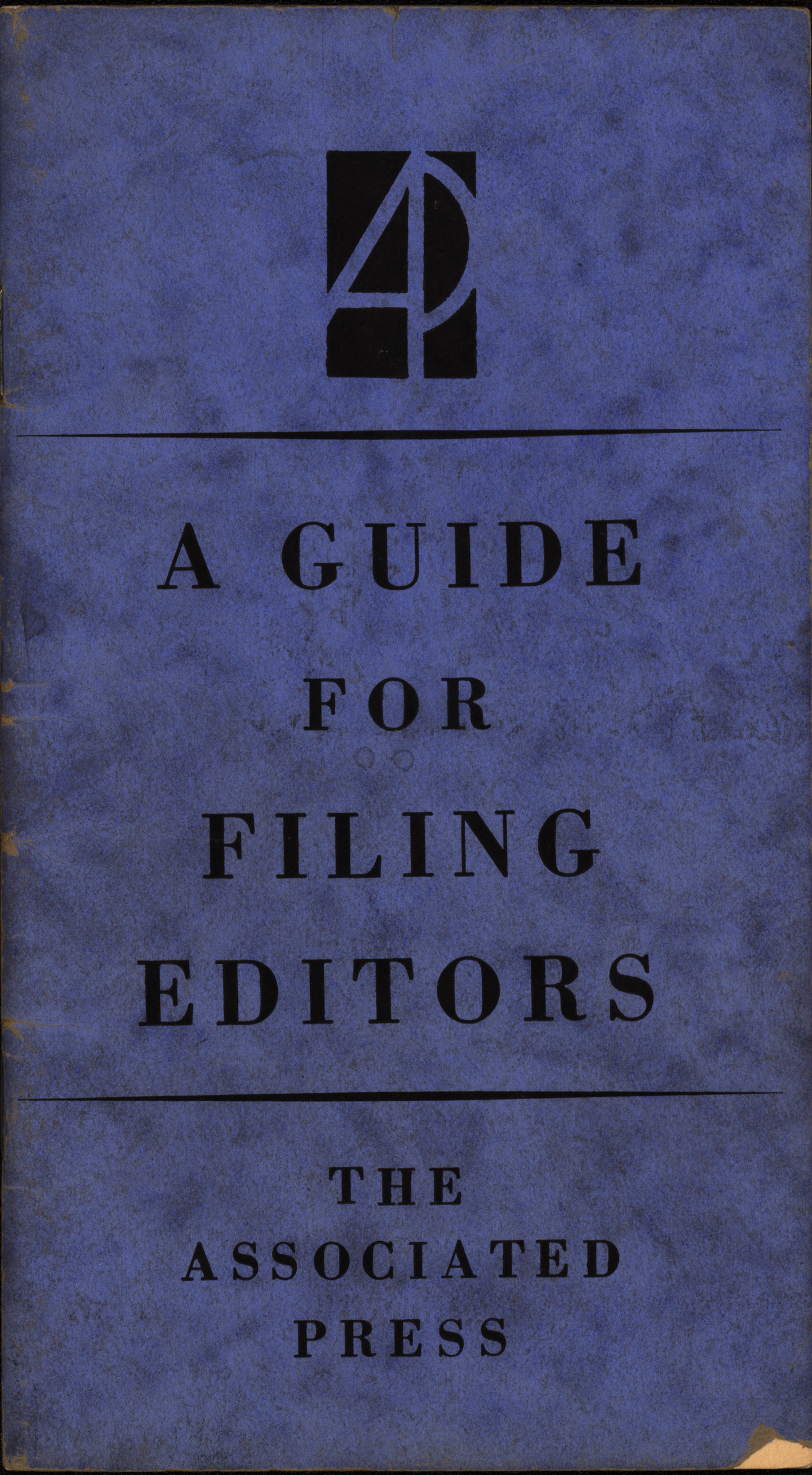

By the 1930s, the AP had three guides: A Guide for Filing Editors, A Guide for Foreign Correspondents, and A Guide for Writers. The foreword to the filing editors’ guide is full of reminders still in force today: “An unbiased and fearless recording of actualities is sought”; “Correctness of statements so far as humanly possible is another fundamental”; “Being reliable is more important than being first.”

Guidelines for filing editors in the “Use of Words” chapter include the current and the dated: “A citizen of Argentina is an ‘Argentine,’ not ‘Argentinian,’” but “A member of the black race is called a ‘Negro,’ not ‘colored.’” Most of that booklet and the one intended for foreign correspondents still concern themselves with the technical aspects of filing stories over physical wires.

The 1931 guide for writers, a 26-page pamphlet, is heavy on advice for sports stories, and often seems reactive to particular incidents, as in this passage, on Page 1, no less: “Where a boy is injured at play, the service does not accept street gossip that a motion picture action was being imitated as a valid basis for so describing the accident.” Was there news of a boy being injured emulating the stunts of Buster Keaton or Charlie Chaplin, both of whose movies were popular at the time?

Then it’s back to the familiar, pertinent in these days of “fake news”: “A statement may be made and turn out to be inaccurate or untrue, but the news would be in the fact that the statement was made. If such a statement is attacked, denied, proven erroneous or false, that makes a new story of itself.”

Next week, we will look at some more changes and similarities through the years, in AP and other stylebooks.

ICYMI: The news has become faster, better, stronger. But how much is too much?

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.