Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

It’s “chilly” out. Let’s make “chili,” with “chiles” or “chilies.” Or maybe “chili oil.”

Okay, the first means “cold,” and the second obviously refers to the stew-like dish. But how come we have two words (at least) for hot peppers or products of hot peppers?

ICYMI: Merriam-Webster reveals its word of 2017

It’s a mystery. To be historically accurate, we would all call the peppers “chile,” since that’s how it is spelled in Spanish. Then again, the Spanish took it from the language of the Aztec (also known as Nahuatl), which used it to describe a local plant that produced hot peppers. But a Nahuatl dictionary (in French!) wrote it as “chilli.”

Let’s get one thing out of the way first: The peppers have no relationship with the South American country Chile, whose name may come from words for the ends of the earth, or from the name of a tribal chief, a neighboring valley, or a bird. But even that nation was called “Chili” until the early part of the 20th century.

The Associated Press Stylebook entry is mild: “chili, chilies Refers generally to spicy peppers, as well as the meat- or sometimes bean-based dish. Exception is the Hatch chile produced in Hatch, New Mexico.” The AP’s section on food guidelines reinforces that usage with an entry for “Thai chilies, Thai chili sauce.”

The New York Times Manual of Style and Usage gets a little stronger: “chile(s) for a pepper or peppers (chile pepper is redundant). But the hearty and usually meaty dish flavored with chiles is chili con carne, or simply chili.”

Then came this mind-blower from Sam Sifton in the Times:

Confusingly, chile powder and chili powder are two different things. (More confusingly, The Times has conflated them for years.) Chile powder is just dried, pulverized chiles. Chili powder, on the other hand, is a mixture of dried, ground chiles with other spices, and it helps bring a distinctive flavor to the dish that bears its name. (Emphasis in the original.)

It’s enough to give you heartburn. So let’s go to the dictionary! Not because it provides “the” answer, but it can at least offer some guidance. And since most publications use a specific dictionary as part of their style guidelines, it can help you sift through the heat of the argument.

ICYMI: Notable changes in AP style

Webster’s New World College Dictionary, the one used by the AP and the Times, sides with the AP on this one, preferring “chili” for the peppers and calling “chile” an alternate spelling. But it also lists “chile relleno” as the preferred form over “chili relleno,” because that’s the way Mexican Spanish spells it.

Merriam-Webster is on the “chili” wagon, too, listing as alternative spellings “chile” and “chilli,” though that last one is chiefly British. So British, in fact, that there is no separate entry for “chili” in the Oxford English Dictionary: It’s included as part of the “chilli/chilly” entry.

So unless you work for the Times, use its stylebook, or follow a specialized stylebook with its own ideas, go ahead and use “chili” all around.

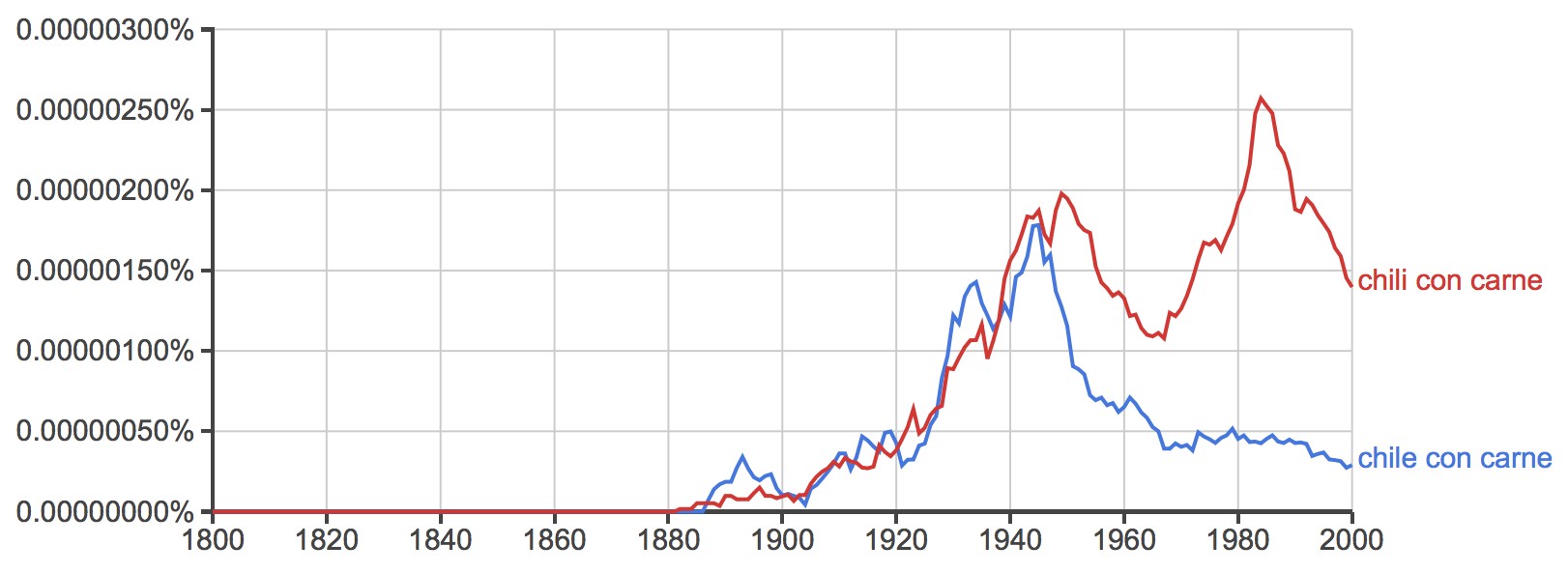

But here’s hot news: The stew-like dish entered English in 1857 as “chile con carne,” the OED says. Here’s a great visualization of how “chile con carne” and “chili con carne” were neck and neck in books until the 1940s, when “chili” took off.

And “chili” is still winning. Go into a store, and you’ll generally find “chili powder,” sometimes even when it’s made out of only one pepper. Many manufacturers and marketers seem to care little how it’s spelled: An Amazon.com search for “chile powder” yields a selection of single-“chile” powders, single-“chili” powders, and blends of both “chili” and “chile,” sometimes in the same description.

Put the spicy little devils in oil, though, and it’s almost universally spelled “chili oil.”

The word “chill” that gives us “chilly” derives, not surprisingly, from words for “cold.”

But here’s one last kick. The hot, desert wind called “sirocco” in many places has an alternate name in Tunisia, the OED says. They call the wind “chili.”

ICYMI: A bombshell scoop that started with an 11-word, late-night text

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.