Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

This summer, more than 500 journalists, many of whom are people of color, signed an open letter calling for changes to US media coverage of Palestine. The letter faulted news outlets for hewing to an objectivity standard that masked the systemic oppression of Palestinians by occupying Israeli military forces. “Finding truth and holding the powerful to account are core principles of journalism,” it read, concluding: “We are calling on journalists to tell the full, contextualized truth without fear or favor, to recognize that obfuscating Israel’s oppression of Palestinians fails this industry’s own objectivity standards.”

Not long after, Mohammed El-Kurd—a Palestinian journalist who grew up in Sheikh Jarrah, an occupied East Jerusalem neighborhood whose Palestinian residents have faced threat of forcible displacement—spoke with The Nation about creating a Palestine Department at the magazine, something he said “all US outlets should do.” In response, The Nation invited El-Kurd to join the magazine as its first dedicated Palestine Correspondent.

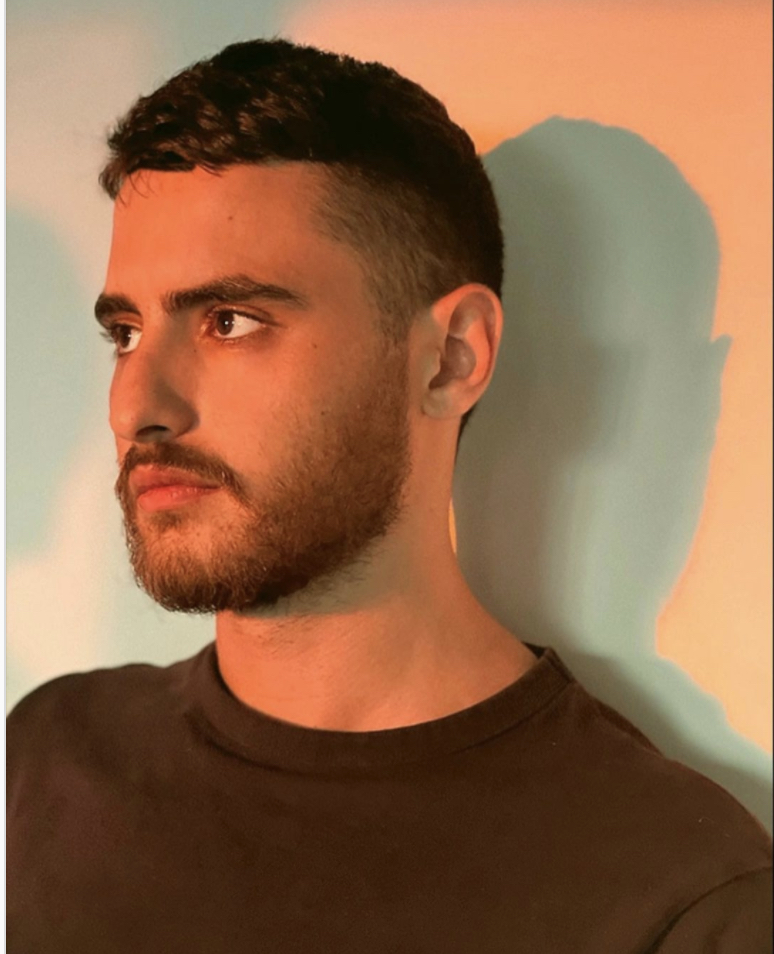

El-Kurd is 23 years old, and splits his time between New York and Sheikh Jarrah. When he was 11, he was the subject of My Neighborhood, a documentary that detailed the forced displacement of Palestinian families in Sheikh Jarrah. (In the film’s opening minutes, a young El-Kurd says he’s “planning to be either a journalist or a lawyer and help people.”) He studied poetry writing at the Savannah College of Art and Design, in Georgia, and is pursuing a graduate degree in poetry at Brooklyn College. Earlier this year, El-Kurd appeared on CNN, where he challenged an anchor’s framing of the violence in occupied East Jerusalem; the clip quickly went viral. Last month, El-Kurd and his sister, Muna, were named to the Time 100 List for “helping to prompt an international shift in rhetoric in regard to Israel and Palestine.” His poetry collection Rifqa, named for his late grandmother—“an icon of Palestinian resistance,” as he describes her in The Nation—was published this month.

In his own announcement of his new position with The Nation, El-Kurd wrote about his plan to cover Palestinian resistance “without burrowing in the sand, using a vocabulary that is loyal to the Palestinian street, and challenging the mainstream narrative about our liberation struggle.” He elaborated on those goals and more in an interview with CJR; the conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

You cannot report on the oppressed without advocating for them.

CJR: Tell me about your decision to reach out to The Nation.

The policies, politicians, money, and weaponry of the US influence the lives of Palestinian people on the daily. There should be a Palestine department in all media outlets that situate Palestinians in their headlines but never go out and seek a Palestinian perspective—or, when they do, take a very tokenizing approach. I wanted to start the trend.

In western journalism, oftentimes there is this marketing of unbiased journalism, objective journalism, and I’m very angered by it. I used to say that I would like journalists to be brave—to take the risk of reporting on topics like Palestine. But, honestly, I just want journalists to do their job. If you’re in Jerusalem and you’re witnessing an internationally recognized military occupation, you should report it as such.

My life has been reported on since I was a child. People have always said that I was threatened with “eviction,” which is a huge misconception about what’s actually taking place in our neighborhood, in Sheikh Jarrah, and what’s taking place all over Jerusalem in general. When we flipped the switch and started calling it “forced mass displacement,” you had all of these nations condemning it. You had the United Nations calling it a war crime, and you had people all around the world showing solidarity with us. That’s what I think journalism can do. I’m not asking journalists to be advocates, but by merely reporting the truth, you become an advocate. You cannot report on the oppressed without advocating for them.

How do you envision your new role?

I’ll report on things like resistance in Beita. But I’m also excited about the possibility of writing about Palestine outside of its geography and its urgency. Palestine is constantly a headline, constantly breaking news. I want to write about what’s it like to be a Palestinian and go to the beach: to see the road, how shabby the Palestinian towns are, versus the settler towns.

I want to continue to be authentic to the people in the street. What was refreshing about Sheikh Jarrah’s rise in American media was that it was the exact same material in Arabic and in English. Oftentimes, when Palestinians talk about ourselves in English, we perform for a Western audience; we assume what they want to hear. In Sheikh Jarrah, our community didn’t do this, and I think that was why it was so resonant.

Your work as a journalist makes you a very visible figure. Does that worry you?

In the occupied territories, the Israeli regime will arrest people for Facebook posts, for “incitement.” I think about that material violence. Like, What happens to my family? Is my family going to be used as a bargaining chip? Is my family going to have to deal with the consequences of my audacity?

I think about prison. I’ve been incredibly lucky not to end up in prison, although I have been arrested and detained. But it’s something that I think about all the time.

With Rifqa, you’re publishing a collection of poems. What should your readers expect from that?

I wrote the book, Rifqa, a long time ago, and I’d been writing it for many years. It’s a book of poems about my time in Jerusalem, my time in Atlanta.

I didn’t anticipate the book receiving this much attention, which is good and bad. It’s good because it’s pretty unfiltered. It’s bad because I should have probably censored myself a little bit more, because it’s going to be in a lot of people’s hands. That being said, I’m very excited about it.

While writing the book, I went from doing the typical “trying to humanize Palestinians”—which I think now is a bad approach—to now just merely writing about things as I see them, unabashedly. I [realized] if I keep writing only about the symptom, it’s never going to be relieved. We need to tackle things at the root, like Angela Davis says.

We shouldn’t spend our energy and time painting perfect victims. This is something that I noticed living here in the US, which has made me kind of transform the way I write about the Palestinian people, about my people, in a way that is more humanizing, not just as powerless victims that are striving for perfection. They have every right to be flawed, living under a situation that forces you to acquire all kinds of flaws and all kinds of furies.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.