Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

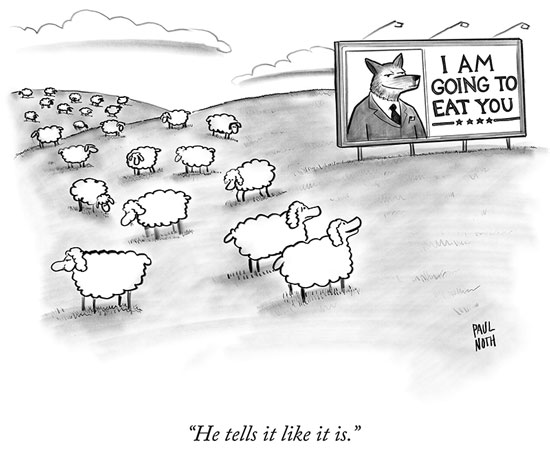

Plenty of Trump-focused political cartoons have circulated the web and social networks since Election Day. But one has drawn particular viral attention: It depicts a wolf in a suit on a campaign billboard with the words, “I am going to eat you,” while onlooking sheep grazing in a field respond, “He tells it like it is.”

Paul Noth, the New Yorker cartoonist who drew it, sold it to the magazine back in January and figured it would never appear. The magazine did run it, in August, but the sketch didn’t go viral until after Trump’s win. The New Yorker added the image to its cartoons Facebook page the day after the election, and that post has been reshared more than 16,000 times. A number of Noth’s single panel one-liners created early in the campaign have garnered newfound attention now that Trump won.

Noth chose to pursue fiction writing after college because he never thought he could make a living as a cartoonist. However, he never lost his love of cartoons and continued to sketch for fun. Noth, 43, spoke with CJR about how he landed his dream job as an artist, some of his other projects, and his political cartoons. The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you become a cartoonist and how did you get your start at The New Yorker?

I’ve always been drawn to cartoons since I was a kid and I always kind of wanted to be a cartoonist. By the time I was in college though, I was more interested in being a writer because it didn’t seem like the cartoon industry was as viable a thing to be a part of.

I’ve always been a big fan of New Yorker cartoons, so I knew how hard it was to break into. So I mainly did cartoons as a hobby and worked towards being a fiction writer. Then one day, I met Matt Diffee, who’s a New Yorker cartoonist, and he and I got to talking. He encouraged me after seeing some of my artwork.

So, it was fall of 2004. I sort of knew the drill at The New Yorker, which was that you’re supposed to submit about 10 per week to give them an idea of what your stuff is like. So Matt helped me, he looked at my stuff, and gave me some notes to help refine it a little bit before showing them to Bob Mankoff, the cartoon editor. Then Bob invited me to come in, and I sold my first batch of cartoons. That was great.

Related: Why the controversy over an Iowa cartoonist is no laughing matter

What cartoons did you enjoy growing up? Who inspires you?

My favorite earliest on and still one of my favorites is Charles Schulz. I just immersed myself in and loved all cartoons from the time I was a kid. My father was a movie critic at the Milwaukee Journal, so he would bring me home reviewer copies of cartoons that came across the features desk. That wasn’t really enough for me, so I would also go to the library and look at them all the time. The first New Yorker cartoonist I really loved was Charles Addams. I used to look through those collections. I was drawn to them and always looking at their work.

What’s your process like to come up with ideas and concepts to submit weekly?

It’s changed a little bit over the years. I think the main thing is having that deadline of 10 a week (recommended submission amount for The New Yorker), that was what really made me learn how to become a cartoonist, because one way or another I have to come up with 10. I’ve tried a variety of things over time. Now I usually start with the writing (the concept) first, then just start jotting down ideas. By the time Sunday or Monday rolls around, I start drawing the ones I think are the funniest. Once I start drawing them, I actually start to see which ones are the best. Sometimes I have to start drawing to actually see which ones work and which ones don’t.

You mentioned that you worked mostly as a fiction writer before becoming a cartoonist. What were some projects that you worked on?

Well I went to college (Emerson College) for writing literature and publishing, hoping to be a writer and that’s what I mainly did after school. Around that same year that I broke into The New Yorker, I started to explore other avenues to make a living. I began doing a little bit of freelance comedy writing for television (Saturday Night Live, Late Night with Conan O’Brien, and Adult Swim). I found that unlike my fiction, people liked it. I would get good feedback on it, but nothing really sold that I could make a living from. I then found with comedies and jokes, that was something I could actually do and get paid for. So that’s what became my main focus in terms of a career. I pitched an animated sketch (Pale Force) to Late Night with Conan O’Brien, that became a recurring thing there.

I’m still writing fiction. I have a series of children’s novels, like middle grade novels, that will be published by Bloomsbury. The first one is going to come out in early 2018. It’s also comedy driven storytelling with cartoons interspersed throughout a series of three books. The first one is called How to Sell your Family to the Aliens. It’s like an absurd funny, sort of like adventure story.

A couple of political cartoons that you created throughout the campaign have recently taken off on social media. What inspired these cartoons and why do you think they are now gaining popularity?

Every week a couple of the cartoons that I do usually turn out to be political. The one with the sheep and the wolf on the billboard, I think that one didn’t run until August, but I sold it as early as January or February. I had a couple of Trump cartoons before that as well so it was a topic on my mind clearly.

There was an issue–The New Yorker seldom does this–but turns out they were planning to do an issue where the cartoons would all be Trump cartoons. So when they put out the call for that, I created the cartoon where they are swearing in Trump. That one, I actually happened to be in the office when that issue was being laid out, that would have been in April. They had the cartoon with the sheep with the wolf billboard and ended up swapping it for the one where he was being inaugurated. So I kind of thought, “oh okay that type of thing happens from time to time and things get rejected so often, the wolf one wasn’t that good.”

So I really didn’t have any idea that both these images had a huge viral response, and then after the election an even bigger one. A lot of times, when cartoons get shared a lot on social media, I may not even be aware of it because people won’t necessarily put my name on it. So it wasn’t until people began to comment and tag me in it that I realized they were everywhere. I think it was sort of a bittersweet thing after the election.

Related: 12 images that capture the new reality show at Trump Tower

There are two other cartoons of mine that gained some attention after the election. One is from August 8, and it’s in the Kremlin. It’s Putin and he’s sitting in the center of a table and they are looking at an electoral map. The entire caption is in Russian except for the last words, which are “…Waukesha County.” translated it means, “It’s all going to come down to Waukesha County.”

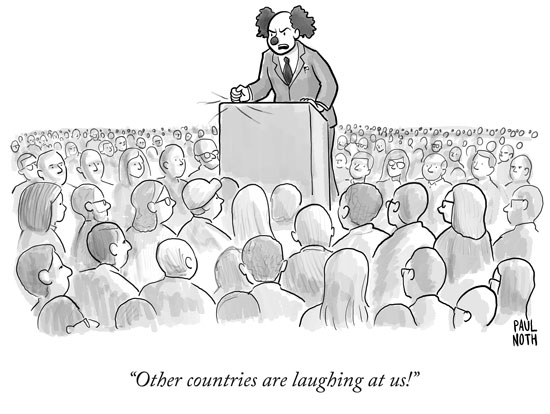

The other one, is a clown at a podium, he looks really angry and he’s slamming his fist down saying, “Other countries are laughing at us.” That one’s had a good response too. The meaning speaks for itself.

Are there any reactions that really stuck out to you?

Well one thing that stuck out is that people began to change the caption. I thought that was kind of funny. Like some post-election thing. For example, the one with the wolf and the sheep someone changed it to something along the lines of “hey let’s give him a chance,” which also works.

Funny enough it begins to morph and change or recontextualize. Sometimes that tweet ends up going viral in different places and not the original cartoon. I’ve made the mistake of scrolling down into the comments of someone’s Facebook post. One time someone texted me and said “Hey Ricky Gervais posted your cartoon,” and I was like “oh that’s cool.” I began reading down the comments and they became calling each other names, you know like how political comments just devolve into chaos.

Over the last couple of years, the industry has seen many cutbacks. How has this impacted cartoonists?

It’s constantly changing, and I think that’s why I felt wanting to be a cartoonist was an unlikely career. You really can’t even plan for it. That would be such a tricky pool shot to bid your life’s hope on. The odds were always stacked against you. It was always hard to get to The New Yorker, but there used to be a lot of other markets. All of the old timers told me to have something else, and pretty much all of us do have something else, with some exceptions. People are genuinely doing it because they really love it, it’s not anyone’s plan to get rich and famous.

Do you think cartoons and cartoonist are still an important part the media ecosystem?

That implies that we ever were. I mean it’s important to me. I love it as an art form, and part of the fun of it is that it’s not, or at least the way I do it, a huge political statement cartoon or heavy duty satire. That’s important, but it’s also hard. I still love cartoons and come up with them all the time and get genuinely happy when I see good work and funny work, and there’s a lot of that both online and in print. So it’s very important to me. It’s always kind of helped keep me sane and I hope that it’s had that kind of role in general.

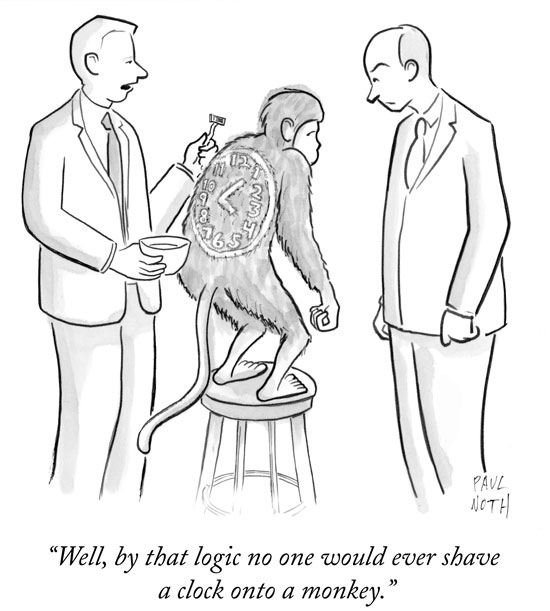

What’s your favorite cartoon that you have created over the years?

Wow, huh. I mean I have this one that baffles people, and I love it. I’ve had a lot of complaints about it. It’s probably my favorite one because I’m defense of it, and it’s had a bad reaction. It’s hard to explain. It’s two guys and they are standing on either side of a monkey standing on a stool, and one of them has a razor in his hand. He’s shaved the face of a clock onto the back of a monkey and the other guy looks like he’s objecting to this. He says, “Well by that logic no one would ever shave a clock onto a monkey.” I get emails about that one from people who are like I went to Stanford and my husband went to Brown and that cartoon makes no sense. I think it’s a pretty straightforward cartoon.

We didn’t get it, either.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.