Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Over the course of eight days in 1978, a 15-year-old terror named Willie Bosket managed to satisfy his curiosity about what it felt like to kill someone. He did this by purchasing a .22 handgun from his mother’s boyfriend, paid for with funds obtained from robbing sleeping passengers in New York City’s subway system, and shooting his next two robbery victims in the head.

Bosket considered the experience to be nothing special, according to Fox Butterfield’s 1996 study, All God’s Children: The Bosket Family and the American Tradition of Violence. But his case soon became a focus of public outrage. At the time, New York prosecutors had no mechanism for trying such a young defendant as an adult; Bosket was facing a maximum of five years in the state’s juvenile system. The furor over the light sentence prompted a new state law that allowed offenders as young as 13 to be tried in adult court for violent crimes. “The New York law marked a break from the Progressive tradition, which since the turn of the century had maintained that children were different from adults and capable of rehabilitation,” notes Jeff Kunerth in his book Trout: A True Story of Murder, Teens, and the Death Penalty.

Over the next 15 years—in a tough-on-crime frenzy that extended throughout the Reagan revolution and well into the Clinton era—lawmakers in other states had their own Bosket moments, granting prosecutors the authority to “direct file” adult charges against juveniles without first requiring a transfer proceeding before a juvenile court judge. They also increased drug penalties; cut prison programs that were supposed to provide skills and education to help offenders return to society; slowed or abolished early release and parole processes; and embarked on a prison-building boom that seemed to be driven not by rational policy, but by lurid press accounts of remorseless, baby-faced killers and predictions about a coming wave of adolescent “superpredators” that never arrived.

The long-term consequences of this rage to punish have been severe. It’s often said that the United States has one of the highest rates of incarceration in the world, but what truly distinguishes the American experiment in mass imprisonment is the length of the sentences involved. We’re good at not just locking up offenders but throwing away the key. As a result, despite declining crime rates, many states are wrestling with budget-devouring prison populations, including a significant number of inmates who were locked up in their late teens or early twenties and have been inside for decades. (Approximately 2,300 of them are serving life without parole for crimes committed as juveniles.) In recent years, fiscal pressures and Supreme Court decisions have prompted a re-evaluation of the reliance on stiff sentences—and have even renewed efforts to implement programs designed to aid parolees in “re-entry,” if not rehabilitation. Two recent books by journalists, reporting on aspects of this shift from opposite coasts, suggest that the pendulum of criminal justice is indeed swinging back toward the possibility of redemption—albeit clumsily and haltingly.

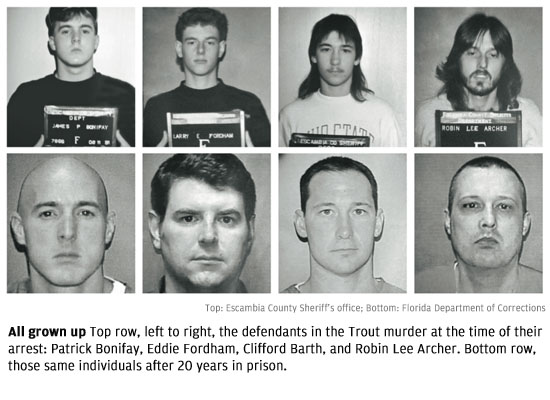

The specter of Willie Bosket looms over Trout, which tracks the downward journey of three adolescents involved in the 1991 robbery of a Trout Auto Parts store in Pensacola, FL, during which a clerk named Billy Wayne Coker was shot and killed. His killer, 17-year-old Patrick Bonifay, didn’t know Coker and may have been hired by his uncle to murder another employee, whom the uncle blamed for getting him fired from the store. The homicide was subject to different interpretations over time, and Bonifay has offered conflicting motives for his actions, but there’s no escaping the essential stupidity and viciousness of the crime. Kunerth describes it as “a premeditated mistaken-identity murder for money inflicted upon an unintended victim who was shot to death while begging for his life.”

A staff writer for the Orlando Sentinel, Kunerth uses this obscure case to demonstrate the disturbing ease with which juveniles are transformed into adults in Florida’s justice system—not just Bonifay but his codefendants, one of whom may not have known that murder was on the menu that night. The police neatly sidestep parental-notification requirements while extracting confessions from two of the teens; the third, already 18, also cooperates and is stunned to learn that he’s being arrested rather than released to his parents. The district attorney plays the naïve crew against each other, persuading one of the group to testify against Bonifay and Bonifay to testify against his uncle, in hope of some leniency—but the state’s felony murder statute makes each defendant liable for the homicide. The defense is perfunctory, the verdicts swift. Bonifay and his uncle get the death penalty, while the other teens end up with life sentences, with the possibility of parole in 25 years.

Bonifay was on death row for only a few weeks, Kunerth observes, before another juvenile joined him there. Florida is one of several states that has no minimum age limit for prosecuting children as adults, and the state has executed inmates as young as 16. But in the late 1990s, emerging brain research, which confirmed longstanding notions about adolescents’ impulse-control issues and thrill-seeking behavior, began to offer a scientific basis for challenging such executions. “Psychopathic behavior in an adult is set in stone,” Kunerth writes, “but the same behavior in a teenager is a common but transitory stage of development that can’t be used to predict who that person will become.” In 2005, the US Supreme Court ruled that the death penalty could no longer be imposed on defendants under the age of 18, citing juveniles’ immaturity, still-developing personalities, and susceptibility to peer pressure.

The decision moved Bonifay from death row to a life sentence. Readers of Kunerth’s brisk, unsentimental treatment of him may wonder if that’s much of a reprieve. Studies show that juveniles tend to have a particularly difficult adjustment to prison life, and the description of Bonifay and his codefendants aging through their long sentences is harrowing. Bonifay, we learn, converted to Islam, recanted his testimony against his uncle, and appears to live largely in a fantasy world of his own devising:

In many ways, Patrick the middle-aged man was still Patrick the teenage boy. Prison doesn’t allow a juvenile to move through the stages and responsibilities of life that produce a mature adult…. Patrick regarded himself as a new man with a new name and a new religion, but in many respects he remained unchanged, a man in age only preserved in prison as a child.

In his loneliest hours, Patrick longed for the certainty of death row.

Whatever new personae they may assume, the convicted teens in Trout remain frozen in time, stuck in a system that’s equally indifferent to expressions of bravado or remorse. The Supreme Court is now considering whether life without parole is cruel and unusual punishment for juveniles, raising the prospect that Bonifay may someday be eligible for release. Nancy Mullane’s Life After Murder: Five Men in Search of Redemption examines the hurdles confronting similarly situated men when the thaw comes. Can convicted murderers lead peaceful and productive lives? Mullane thinks so; she finds hope, at least, in the discovery that most killers, despite their bad press, turn out to be human after all.

In 2007, Mullane, a San Francisco-based reporter and producer for This American Life and other public-radio programs, began an assignment on California’s overcrowded prison system. She quickly became fascinated with the individuals behind the numbers—and with the state’s convoluted and deeply politicized parole process, an obstacle course of hearings and setbacks and reversals that has contributed to the logjam. Over the next four years, she followed the efforts of five San Quentin inmates, all convicted of murder, to obtain release and make a life for themselves on the outside, a project that resulted in her book and a two-hour radio documentary.

Mullane’s killers were young men when they committed their crimes—some not yet out of their teens. Unlike the elaborate and purposeful mayhem depicted in crime dramas, most real-life murders are dumb, impulsive outbursts of violence. Even the minimal planning of the Trout robbery is missing from the accounts of random bloodshed the inmates relate to Mullane, committed by young hotheads they no longer recognize. “Ended up going out one night to do a robbery and ended up shooting a man and killed him,” one says, adding that his arrest was “sort of like a relief”: “I didn’t like the way I was living at all.”

Mullane admits to letting her imagination run wild during her first visit to San Quentin: “I survived being in a small room, alone, with half a dozen murderers, and they didn’t try to kill me when they had the chance.” She seems a bit wide-eyed about prison life, dwelling on details, such as the claustrophobic cells, that should already be familiar to any viewer of MSNBC’s Lockup or similar reality shows. She’s amazed that there’s a sweat lodge available to Native Americans and gets chewed out for hugging a downcast prisoner, in violation of no-contact rules. More troubling, though, is her willingness to accept at face value the inmates’ somewhat self-serving accounts of their crimes. She makes use of court documents to flesh out one inmate’s story and visits restorative justice programs, in which prisoners and crime victims interact, but she also declares her lack of interest in interviewing victims’ families; she doesn’t even seek out the niece of one homicide victim who’s actually supporting the killer’s parole. This is a curious omission. The perspective of victims’ families can not only provide a reality check on a convicted felon’s version of his crimes, but also offer insights into the burgeoning power of the victims’ rights lobby, which has had an enormous influence on legislation and sentencing policy.

It’s just such political considerations that have spawned California’s highly dysfunctional parole system. The “lifers” Mullane profiles have indeterminate sentences and a shot, in theory, of being released someday. Regardless of their accomplishments inside—earning college credits, completing substance-abuse programs—they are turned down for years before being granted parole. But that isn’t the end of the process. California’s governor can overrule the parole board’s findings; the aspiring convict must wait another agonizing five months to learn if the board’s grant of release will stand. Often, it doesn’t.

The statistics Mullane compiled are revealing. Of the thousands of lifers in the state eligible for parole in a given year, only a handful are found suitable for release—and most of those have their parole overturned by gubernatorial fiat. Pete Wilson approved only 131 lifer paroles during his eight years in office. Gray Davis let out a total of eight in six years. Arnold Schwarzenegger rejected only about three-fourths of the approved paroles that crossed his desk.

This adamant refusal to parole murderers, even if they’ve become model prisoners and fit all the criteria for release, costs the state hundreds of millions of dollars a year. But it’s hardly surprising; what future presidential candidate wants to have the next Willie Horton dogging his or her campaign trail? Yet all of Mullane’s profile subjects eventually did get out, thanks in part to a 2008 California Supreme Court ruling that parole can’t be denied simply because of the heinous nature of the crime. Although the governors invoked public-safety concerns as the justification for their denials, it’s a feeble argument in the case of long-term prisoners with good records. Lifers can get institutionalized and have problems returning to society, but they are statistically less likely to reoffend than younger felons. Mullane contends that it’s the prisoners released with little assistance after serving determinate sentences who pose the greatest safety risk: “Of the 1,000 prisoners paroled by the State of California in the past 21 years who were serving a sentence of life with the possibility of parole for committing murder, not one has committed murder again.”

Mullane chronicles the lives of the five parolees as they leave prison, reunite with long-suffering families, get overwhelmed ordering from menus, and struggle to find work and forge new relationships. The devastation their crimes left behind, not to mention the void in themselves, can’t be easily remedied. (One of the five is the father of two boys who were two and eight years old when he shot the drug dealer who stole his wife; by the time he gets out, they’re in their twenties—and in prison.) Mullane is there to observe many of the events she recounts, in contrast to Kunerth’s more conventional true-crime technique, which involves dramatizing scenes culled from interviews with the participants—a tricky business when the sources’ stories don’t agree. Mullane’s radio-reporter approach seems more intimate at first, but I soon became too conscious of her as a chatty presence in the story, dropping in on the men in the hope of gaining some revelatory bit of action and even inviting the whole crew to Thanksgiving dinner in order to provide a parting scene. The tightwire that parolees must walk isn’t empty of drama, but a successful re-entry doesn’t have a tidy ending, just a slow settling in to something like normalcy.

Still, it’s encouraging to learn that none of Mullane’s subjects had violated parole by the time she completed her research. Her account manages to put human faces on people who are too often demonized by the media—and then forgotten. As its title suggests, Life After Murder makes a strong argument that a sane sentencing policy should address the reality that, long after even the most terrible sins of youth, people can change.

Sadly, the change isn’t always for the better. Some teen offenders become inured to prison life. Willie Bosket escaped from a youth facility and was sent to an adult prison. He committed other crimes during his brief periods of freedom, was sentenced as a habitual criminal, then was convicted of assaults on staff while housed in a maximum-security prison. He won’t be eligible for parole until 2062, when he’s 99 years old.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.