In the imaginations of her detractors, Carole Cadwalladr’s apartment, in North London, should be empty, except maybe for a wall outfitted with corkboard and covered in news clippings about Mark Zuckerberg and Alexander Nix, the CEO of the now-defunct targeted-advertising firm Cambridge Analytica. But Cadwalladr, I was happy to discover, lives in an elevated row house set in a charming brick complex. On the April afternoon I was there, I saw a small balcony brimming with untamed plants, a bright yellow Smeg refrigerator in the kitchen, and a vintage poster advertising Lucky Strike hanging on a wall. Still, there was evidence of the indefatigable reporting life behind her work for The Observer, the Sunday edition of The Guardian: on a table was a copy of How to Lose a Country: The 7 Steps from Democracy to Dictatorship, a new book by a Turkish journalist named Ece Temelkuran.

Cadwalladr is forty-nine and tall, with wispy blond hair, her style a mixture of femininity and rebelliousness; she often wears a black leather jacket over a flowy top. When I entered her home, she offered me tea. Then she begged my pardon; her throat was sore and her voice was nearly gone. She’d delivered a speech the night before at the National Press Awards, where she’d accepted the title of Technology Journalist of the Year. “I do a lot of events,” Cadwalladr said. “This is the only time I’ve ever been jeered.”

Given the opportunity to address her peers, most of whom were working for pro-Brexit papers, she’d been seized by a desire to provoke them. The previous week had been Britain’s deadline, foreseeably missed, to leave the European Union; thanks in part to Cadwalladr’s reporting, the official Vote Leave campaign had agreed to pay a fine in response to charges that it had broken election law in its pro-Brexit spending. From the podium, Cadwalladr told her colleagues that they now knew the Brexit vote had not been free or fair. “And they were like, ‘Yes, it was!’ ” Cadwalladr mock-shouted. She laughed, sounding hoarse.

To some, Cadwalladr’s stubborn idea of justice makes her grating. To others, she’s frustrating because she’s right.

Cadwalladr’s journalism, her combination of assiduous investigation and prolific output, has earned her a reputation as something of an instigator, a role she publicly embraces. In conversation she is chatty, personable, and kind; her online persona, however, is more combative. On Twitter, she slings fireballs at her critics, who include powerful figures in politics, business, and Silicon Valley. She has a stubborn idea of justice, and will frequently reach out to writers, editors, or anyone else she believes has engaged with her or her work unfairly or used a sexist trope. To some, that makes her grating, though it is difficult to imagine a male journalist eliciting the same reaction. To others, she’s frustrating simply because she’s right.

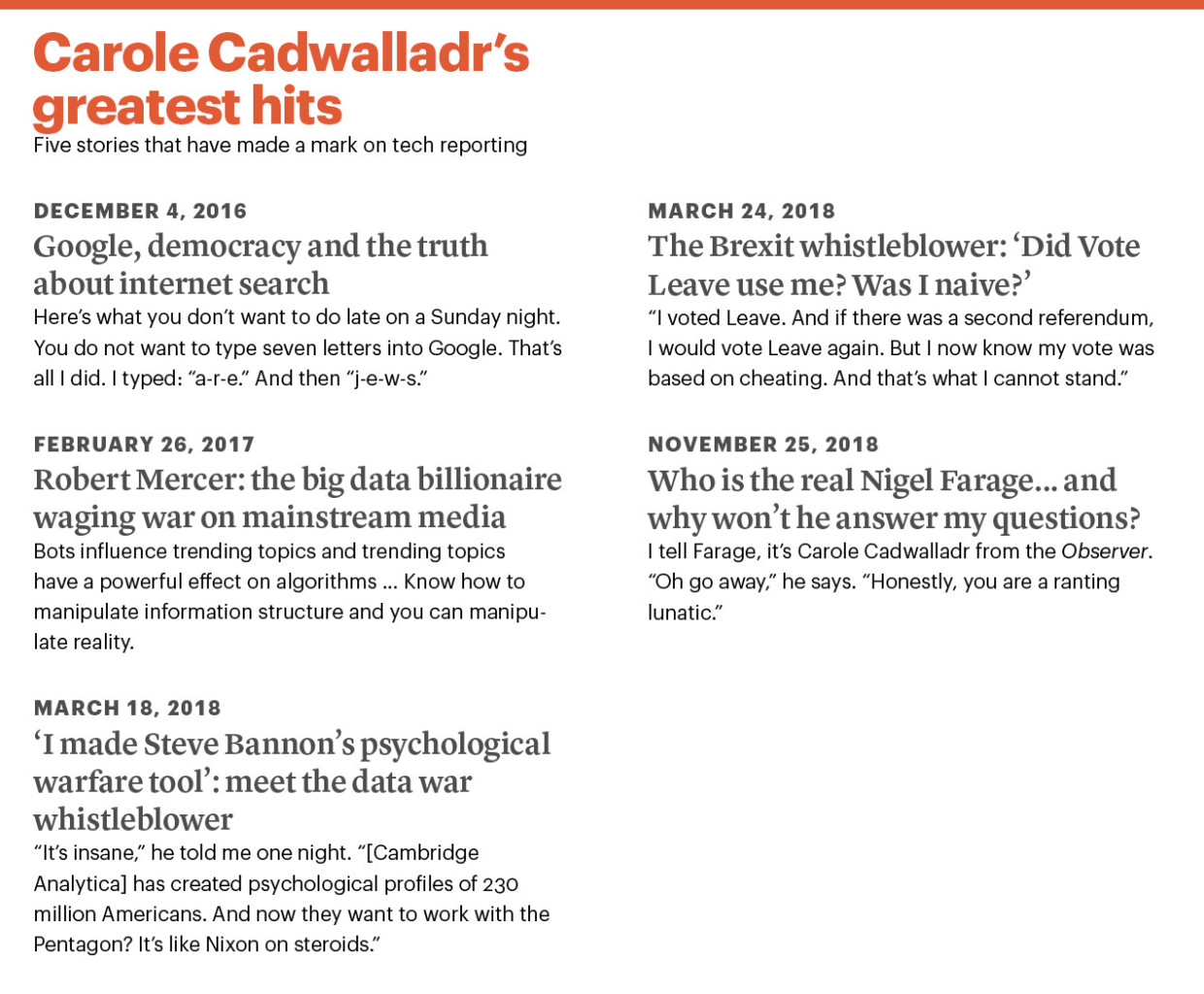

Cadwalladr has written for The Observer since 2005, tackling everything from food waste to the effects of “smart drugs” to Adele and Marilyn Manson. She has always had a particular curiosity about the promises of new technologies, as well as their off-label potential. And then, at the end of a long 2016, she began devoting the weekly space allotted to her to a series exploring how social media platforms, especially Facebook and Google, had been negligent bordering on malicious with regard to their amassed power and resulting democratic responsibilities.

She writes—as Sarah Donaldson, her editor at The Observer, remarked to me—as she speaks, in chatty, playful prose replete with rhetorical questions and personal reflections, in a way that feels intimate: a reader of Cadwalladr’s may feel that she’s joining a quest inside the author’s mind. Her background is in feature writing, rather than investigative reporting, which means that her dissections of tech platforms make use not of the seemingly neutral and omniscient style that often characterizes tech journalism, but rather her singular voice. “We are the bounty,” she wrote in 2017. “Our social media feeds; our conversations; our hearts and minds. Our votes.”

Cadwalladr’s recent work has traced the arc of popular understanding about interference in British and American electoral processes by foreign actors. Before Brexit, there had been two articles about Cambridge Analytica’s use of breached Facebook data that received little attention; Cadwalladr first mentioned it in a piece about Robert Mercer, the hedge fund tycoon, in February 2017, and was followed about a month later by Jane Mayer, who published an investigation of Mercer in The New Yorker. Up to that point, these stories represented the most extensive coverage of the subject, detailing Mercer’s substantial donations to Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign and noting that he had invested millions in Cambridge Analytica—a firm that had worked on campaigns supporting Trump and Brexit by using data to wage “political and psychological warfare.”

An acquaintance of mine who holds a high-level position at Facebook in Europe said that she had remained unfamiliar with the name Cambridge Analytica until the spring of 2018, when Cadwalladr broke the story that the firm had used data from fifty million breached Facebook profiles. The news was published as an interview with Christopher Wylie, a data consultant for Cambridge Analytica whom Cadwalladr had spent a year persuading to become a whistle-blower. The Observer ran the interview in consortium with the New York Times (where Cadwalladr’s byline appeared along with Matthew Rosenberg’s and Nicholas Confessore’s) and the British television station Channel 4, in order to garner international attention. The story unleashed a resounding international response and incontestably altered public perception of Facebook across Europe and the United States.

A week later, Cadwalladr published a second whistle-blower article, this time focused on Britain and Brexit, featuring an interview with Shahmir Sanni, a former campaign volunteer for Vote Leave. The Sanni story, which detailed how the Vote Leave campaign intentionally flouted spending limits, and thus broke the law, should have led to swift political and public consequences. But it fell flat, largely because, for more than a year, other British media declined to pick it up (Cadwalladr speculates that papers with a pro-Brexit slant were disinclined to question the outcome of the vote). If the American press is increasingly entrenched on opposite sides of an impassable chasm, the British press, Cadwalladr claims, is worse. Much of the British print media is immovably right-wing because of Rupert Murdoch’s empire, whose holdings in the UK include The Sun, The Times, and the Sunday Times. “One of the biggest failings was the fact that the BBC didn’t report it,” Cadwalladr said. “If it doesn’t happen on the BBC, it doesn’t happen in Britain.”

As we sat in Cadwalladr’s kitchen, Chris Wylie texted her: “we need to fucking stop this bullshit.” He’d just found out that Alexander Nix would be speaking publicly for the first time since the Cambridge Analytica revelations—at the Cannes Lions festival, in the South of France. (He later canceled the appearance.) During the year prior to Wylie going public, Cadwalladr had sometimes spent two hours per day on the phone with him. Now she put her phone away. “Should we go for a walk?”

We headed out with Meg, her aging collie–golden retriever mix. Cadwalladr’s neighborhood is modest in appearance but sits adjacent to the city’s largest private home, a Georgian Revival manor called Witanhurst, which in 2008 was sold to a holding company belonging to a Russian oligarch for fifty million pounds. Highgate, the area around Witanhurst, is flush with Russian money (along with Kate Moss’s and Jude Law’s). Near Cadwalladr’s complex and the oligarch’s sits the cemetery where Karl Marx is buried.

Striding ahead, Cadwalladr took me past Witanhurst, then turned with Meg down a driveway blocked off by a red-and-white striped barrier, the word private painted across the pavement in large white letters, as she detailed the fallout from her reporting on Cambridge Analytica. “The multiplicity of my enemies is quite something to behold,” she called back to me as I straggled behind. Google and Facebook had both threatened to sue The Guardian; Nix had become an adversary, as had Julian Assange.

After twenty minutes of walking, we arrived at our destination: a school-like brick building that, Cadwalladr said, once bore a sign labeling it as the Russian defense attaché’s office. By now, Robert Mueller, the US special counsel, had indicted thirteen Russians for their role in the social-media-catalyzed chaos that seized America. Cadwalladr told me that, since the Skripal poisoning—in 2018, when Sergei Skripal, a former Russian military intelligence officer and double agent, and his daughter Yulia were mysteriously poisoned with nerve gas in a small city in southwestern England—some residents of the building before us had been expelled from the country and the building’s sign had been taken down. Now the only marking on it offered a number to call for deliveries. “It’s basically a nest of spies,” Cadwalladr said.

That, in her view, represented one of the most trying aspects of her reporting—we now know what disinformation schemes happened, who was involved, and how. The facts are out in the open, acknowledged by all, but the British government has been unable to hold digital platforms like Facebook responsible, and the American government seems mostly unserious about doing so. Speaking of Trump’s election and the Brexit debacle, Cadwalladr told me, “We know this is all faked, billionaires using millions to control political systems on both sides of the Atlantic.” She called it “plastic populism”—political figures supported by a minority of constituents and propped up by dark money. “We do have to keep on trying to expose that,” she said. “The vast majority of people who understand it see that, too. It just feels somewhat like we’re running out of time.”

Defamation laws are notoriously more generous to the accuser in the UK than in the US, and it’s a well-tested strategy for US companies to threaten to sue publications in the UK in order to stop publication of a story—which is what had happened to The Observer repeatedly with Cadwalladr’s pieces. When she and the team at the New York Times, for example, reached out to Facebook for comment prior to the publication of the Wylie interview, Facebook responded with an eleventh-hour call to London. “We were very near to publishing, and we got this very threatening letter from Facebook basically trying to stop us and threatening to sue us,” Emma Graham-Harrison, a Guardian and Observer reporter who worked with Cadwalladr, told me. “And we ring up the Times and they’ve not got anything like it. Because they know they can’t shut the New York Times up.” But when I visited The Observer’s office, Cadwalladr and her editors were celebrating some news: Cambridge Analytica had dissolved, and with it, their associated legal angst.

Cadwalladr’s tech antagonism started out, as with so many people, as tech utopianism. She grew up in Wales, far from the insular private-school milieu that produces much of the political and media establishment she now inhabits. In 1988, she arrived at Oxford, entering the destabilizing world of money, prestige, and social elbowing. In her second year, she took time off from her studies to teach English in Prague. Eventually, she graduated and took a job writing travel guides for countries of the former Soviet Bloc. Then she returned to London. “I was like, ‘Oh, shit, I’d better actually do something,’ ” she said. In her mid-twenties, Cadwalladr took a traineeship—Europe’s version of a paid internship—at the Daily Telegraph, which provided her with funding to complete a journalism school program and then set her up on the travel desk. In 2003 she took a buyout and used the time off to write a novel, The Family Tree, which was published in 2005. The book was a quirky comedy that followed a young academic working on a thesis about pop culture and her husband, a rock-star genetic scientist. They both want to know whether her tragic family history lies in her DNA.

The husband character was loosely modeled on the Harvard cognitive scientist Steven Pinker, with whom Cadwalladr later struck up a correspondence. He invited her to attend one of the first ted conferences, in 2005, before ted went mainstream. “It was still the secret rulers of the universe,” she told me, “a mind-blowing lineup.” Jimmy Wales, the founder of Wikipedia, spoke, as did the quantum theorist David Deutsch. “There was this intensity of all these different ideas,” Cadwalladr said, “and it was exciting at the time how they were exploring all these new ways of global online network collaboration.”

The novel was a critical success, and The Observer offered her a contract as a features writer—a dream job. In 2013, building off the research she did for her novel, she took a genetic sequencing test and wrote a story about it. Shortly after, she did a piece in which she took a job for a week as a temp worker during the Christmas rush at an Amazon warehouse (a “fulfillment” center, she joked, for the “wilder reaches” of consumer desire—items she processed included a dog onesie and a cat scratching post designed to resemble a record player). Her story was scathing.

In a speech streamed more than three million times, Cadwalladr attacked Facebook for “spreading lies in darkness paid for with illegal cash.” Marla Aufmuth/TED

After the Amazon piece was published, Cadwalladr considered what the company could do should it choose to take revenge on her. She did some research and learned that the data from her DNA test was being stored in the Amazon cloud. “I’d heard all about their ruthless business practices, and I was like, ‘How can that information be used?’ ” Cadwalladr told me. A few months later, The Observer hosted a Q&A with Edward Snowden as part of its ideas festival; he video-conferenced in, but there was some kind of interference that prevented him from hearing his interviewer; Cadwalladr, who was offstage, sent him questions via instant message. Thinking about the massive surveillance capabilities of giant platforms, an intense feeling of vulnerability overwhelmed her. She began to rethink her optimistic beliefs about the future of tech. “Suddenly, I was just alive to the authoritarian possibilities of that,” she recalled. “All sorts of weird sci-fi-y things you could do with somebody’s whole genome—you can reverse engineer a kind of organic poison which would only work on them, for example.”

The months after Trump’s election were characterized by heightened feelings of uncertainty. Late one Sunday night, Cadwalladr wanted to test the hypothesis that social media sites were neutral platforms, so she typed into her Google search bar: “a-r-e-j-e-w-s,” until autocomplete kicked in. One of the top suggestions was: “evil?” She clicked. The third link on the results page was a neo-Nazi website, and the sixth was a Yahoo Answers Q&A forum in which people could, presumably, post earnest answers. (One of Cadwalladr’s results proclaimed: “Jews today have taken over marketing, militia, medicinal, technological, media, industrial, cinema challenges etc and continue to face the worlds [sic] envy through unexplained success stories given their inglorious past and vermin like repression all over Europe.”) In a freewheeling piece, published in December 2016, she described how right-wing organizations game internet algorithms with extreme messages, drawing increased engagement, which boosts their search engine optimization.

On Christmas Eve, Google hit The Observer with a letter threatening legal action. It reminded Cadwalladr of her post-Amazon-story panic. “Again, I’m thinking about the amount of data that Google has on me,” Cadwalladr said. She wrote an email to her editors in which she noted that The Guardian’s accounts, including hers, were run on Gmail. “You know in your Gmail you can go and see what data they’ve got on you,” she recalled. “And it was just, like, I was so creeped out. Because they have every single Google search for like ten years.” As Cadwalladr’s reporting continued, a member of Google’s communications team regularly rang up her editors, trying to dissuade them from running her work. “They were publicly trying to smear and discredit me, and I was just thinking about what it means when they have so much information on me,” she said.

“The whole thing of reporting this story is that it gives you terrible paranoia, but it’s not actual paranoia when people are out to get you,” she explained, of covering tech platforms. In the months before her Chris Wylie interview was published, threats were made against him, too. “I probably am oversensitive to some things, but my threat level is high,” Cadwalladr told me, “because I am under attack from so many different angles.”

After Cadwalladr’s first Cambridge Analytica story, in 2017, she’d gone through LinkedIn profiles of anyone who’d worked for the firm and sent them messages. No one responded. Finally, a former employee agreed to meet her, and he told her that she needed to find Wylie—he was the guy, the former employee insisted, who knew about the use of Facebook data. After tracking Wylie down, Cadwalladr considered taking the story to The Guardian’s news team, and they tried to figure out how to squeeze everything readers needed to know into a seven-hundred-word news article. But it was too big for that. Cadwalladr had been affected by the words of Adam Curtis, a filmmaker, who once argued that journalism had failed during the financial crisis because “journalism is a trick to find a way of making the boring interesting”—something that financial reporters neglected to do. Cadwalladr realized that she needed the narrative expertise of The Observer. “I went out and walked up to the Observer Sunday review desk—at the time the newsroom was very male and the review desk was very female—and I was like, ‘Right, that’s it. The men aren’t up to it. The women are going to have to do this,’ ” she recalled. The Wylie piece, she said, “had to be a narrative long read, because otherwise you don’t get the sense of the scale and the story.”

After the Wylie interview went viral, Cadwalladr saw the reaction of a former investigations editor of The Guardian, David Leigh, who tweeted: “Scariest investigation I’ve read this year.” Cadwalladr was surprised. “I was like, is it?” Then she thought, “Shit, okay, I’ve got to keep on investigating. But I don’t know what an investigative reporter does.” Later, she reached out to Clare Rewcastle Brown, a journalist in London who ran an independent news website that helped to uncover a money-laundering scheme worth billions of dollars. Rewcastle Brown told Cadwalladr the secret to her work: chatting with people. “She said, ‘Oh, you know these men, they go crazy for these big data dumps.’ And she was like, ‘Every one of my stories has come from a person.’

“Chatting to people was the foundational skill that I had,” Cadwalladr told me. In 2017, she contacted an associate of Arron Banks, an insurance executive who was behind Leave.EU, an unofficial Leave campaign. The man agreed to chat and told her to give him a call. Her modus operandi, however, is to avoid the telephone. She asked to meet in person. He invited her to coffee and, feeling open, ended up showing her photos on his phone from a trip to Washington for Trump’s inauguration, as well as pictures with Nigel Farage, the bumptious leader, at the time, of Britain’s UKIP party, and Donald Trump, in Trump Tower. Then he told her that Cambridge Analytica had worked for the Leave.EU campaign. Afterward, she said, “I rang up the electoral commission and I was like, ‘If you get given a gift of services, is that a donation?’ And they were like, ‘Yes.’ So I was like, ‘You have to declare it?’ And they were like, ‘Yes.’ ” That’s how she learned that Leave.EU had broken the law.

When I asked Cadwalladr if she had any free time in which to do anything besides work, the question seemed to unleash a deluge of nostalgia. She told me that this summer she’d spent a week in Greece, a few days in Sussex after a journalism festival there, and had been invited by friends for a week on Martha’s Vineyard. She’d attended the premiere of The Great Hack, a Netflix documentary about Cambridge Analytica. But most of her friends are not journalists, and so much of her life was spent promoting her work or dealing with its effects; even on trips, she was never without her phone. “It’s so hard to free your brain these days—this thing of us all being online all the time,” she told me. Watching the Netflix documentary had an element of reliving trauma. “I had this revelation,” she said. “From the outside it looks like professional success and great triumph and all that.” But at the London premiere, when the moderator of a panel discussion asked her how the story had changed her life, she became emotional. “I said it has changed my life and not all in good ways.”

Cadwalladr has been on contract with The Observer for fifteen years, but she’s technically a freelancer and mostly works from home. That has given her the freedom to spend three months on a single beat if she wants; it also has given her allowance to let her social media personality publicly intermingle with her work a bit more than if she were in the office every day. When subjects of her stories taunt her, she responds in kind: “You must have found a date tonight on ‘the Losers’ March’ or is it another night in with the cats,” Banks tweeted at her in March. “Darling, don’t worry about me. You’re the one married to a suspected Russian asset,” she tweeted back, appending a red-lips emoji. A gif showing a woman throwing fistfuls of kibble at a herd of cats gets tweeted at Cadwalladr frequently by various Brexiteering trolls; in July, she retweeted one of her followers, who had modified the caption on the gif: “This is the only pussy you get arsehole.”

“I think maybe if Carole was on staff, she would not respond quite as freely and as openly as she does,” Donaldson, Cadwalladr’s editor, told me. “If you’re a staff member, your boss or somebody here might say you shouldn’t be doing that, because, you know, it’s not great for you.”

Cadwalladr’s critics claim that her tendency to push her theories online detracts from her credibility in her reporting. An editor of a conservative paper in London told me recently that she has become an activist, for whom political mission comes first, and accuracy second. To be sure, Cadwalladr has had to make some corrections, for example on a follow-up story about Brexit funding; but small fixes are made on investigative pieces all the time. That’s the necessarily incomplete nature of investigative work. By covering the malicious use of technology behind the Brexit campaign, Cadwalladr became embroiled in a political feud as intransigent and all-consuming as that between pro- and anti-Trumpers. Everything, in this scenario, becomes an attempt to push one’s party line. “That’s where I get tarnished and attacked—it’s because of politics,” she said. “Even when I say that, for me, it’s really not about left or right, it’s bigger than that.” When rivals argue that Cadwalladr fails to provide a balanced picture—that even her important breakthroughs are undermined by partisan zeal—her response is: “The easiest way to attack the story is to attack me.”

Still, her methods do, sometimes, veer into the atypical. For instance: She tried for years to speak with Nigel Farage. When he turned her down, she called in to his radio show to ask a question live on air, several times, under various pseudonyms, before getting kicked off. Finally, she discovered that Farage would be giving a public talk in Australia. So she flew out, bought a ticket to the event using Donaldson’s credit card, and paid an extra $200 for a pass backstage, where she finally introduced herself to Farage, who snapped a photo with her before he realized who she was. I asked Donaldson whether these weren’t kind of unconventional methods. “But they’re unconventional people,” she replied. She might have meant Cadwalladr, too. Then again, this is a trope applied to many of the most successful investigative journalists: that they see connections and seek out hidden explanations that, to the rest of us, seem exaggerated—until it turns out they aren’t.

For all the people Cadwalladr has managed to set against her, she maintains that her real adversaries are the tech platforms. She sometimes adopts the sweeping rhetoric of whistle-blowers, relaying lofty principles of civic virtue and justice, when she makes predictions about how tech will control the future. In the spring, when the British Parliament was stuck in a deadlock, and a bevy of ads appeared on Facebook pushing for a hard Brexit, Cadwalladr wondered: “How is it possible, in 2019, that someone is giving one million pounds to Facebook ads, and no one knows who it is?” Then, referring to the British government’s failure to pass new regulations to keep apace with Facebook’s innovations, she added, “No one gives a shit.”

Cadwalladr’s critique is also a journalistic one. Part of her success in making stories on disinformation campaigns digestible to a broad audience, she argues, is that she’s a generalist, not a tech reporter or “tech bro”; she writes about tech in non-geek terms. Every journalist (and every citizen) now lives with, and therefore should be versed in, the influences and consequences of tech, and she believes that mainstream media outlets have been too slow to bring tech coverage out of its specialty status and turn it into a central element of general political coverage.

The most successful investigative journalists see connections and seek out hidden explanations that seem exaggerated—until it turns out they aren’t.

Europeans tend to be warier of Big Tech than Americans are, and Cadwalladr has found particularly kindred spirits in Germany, where the culture of data privacy and skepticism toward far-reaching power is exponentially more robust. Cadwalladr is frequently interviewed by German reporters and documentary filmmakers and, a few days after I met her at her home, I sat in on an interview at The Guardian’s offices with the German public broadcaster ZDF, about her reporting on the Leave campaign’s illegal spending.

In a top-floor room, Cadwalladr sat facing a camera. The members of the ZDF crew were people she already knew. “It’s been another hell of a week,” Andreas Stamm, a ZDF correspondent based in London, told her. His editor in Germany wanted a constant stream of Brexit coverage. “It doesn’t stop, and the interest doesn’t stop,” he complained.

“Oh, God, you poor thing,” Cadwalladr responded.

Then the camera started rolling, and her interviewer turned into a stern German. “Some people claim that the effect of targeted ads is maybe not that big,” Stamm said. “How much of an effect can it have on people, and especially on those who vote?”

Cadwalladr sometimes speaks in long, labyrinthine spools of thought. Here, she was cool and clear. “I think that people misunderstand the way that political advertising works,” she said, looking solemnly into the camera. “Because they think of it as in the olden days: Political adverts were billboards in the streets and they were adverts on the television. And we all saw them, and it was broadcast to the entire population. These targeted ads are very, very different. They’re targeted to a tiny sliver of people who have been identified, using different techniques. Most of us don’t see them.” She went on: “They found this tiny section of the population who were persuadable. And then it targeted them with a fire hose of disinformation and lies.”

During the Brexit campaign, Vote Leave ran ads claiming that Turkey was about to join the European Union and that if Britain remained, there would be thousands more immigrants—Muslims—en route to the British Isles. It was a lie—a racist, fearmongering one. But most Brits weren’t even aware that those ads existed, because the message had been targeted only to certain demographics. “The key period was just in the very few days before the vote,” Cadwalladr said. “It was the last twenty-four and forty-eight hours which were critical. And that was when this illegal money was used.”

She was exasperated but offered a faint smile. “The idea that that had no impact,” she said, “I find farcical.”

Later that month, Cadwalladr flew to Vancouver to give a ted Talk. This was an opportunity par excellence to provoke: Jack Dorsey, one of Twitter’s founders, was going to be at the conference, and the event was sponsored by Facebook and Google. She expressed to me a mixture of trepidation and relish when she described the chance to address her opponents directly. The talk has now been viewed more than three million times.

Onstage, the mic snaking along her left cheekbone, she lambasted Facebook for its refusal to release information that would help the public understand who had been targeted by what kind of advertising, and why. She addressed the “gods of Silicon Valley” and spoke about Facebook’s legal threat against The Guardian and The Observer. She accused Facebook of “spreading lies in darkness paid for with illegal cash” and wondered whether it was possible to ever have a “free and fair” election again. “As it stands, I don’t think it is,” she said.

After the ted Talk went live, Arron Banks, the Leave campaigner, filed a lawsuit against Cadwalladr for libel because she had mentioned, nonspecifically, the “lies Arron Banks has told about his covert relationship with the Russian government.” Since then, the lawsuit has weighed heavily on her—Banks isn’t going after ted, but her personally, which means that she could lose her home if the court rules against her. “He’s trying to shut down reporting,” Cadwalladr told me. He was under criminal investigation, she went on, “I’m the journalist who has helped get those investigations opened, and he is going after journalists who’ve done that in a way that threatens to put me out of my house. It’s a really vicious assault on the press.” The case could take a year to come to court, and it’s keeping Cadwalladr away from other reporting. The Guardian won’t pay for her legal defense, so she has turned to crowdfunding: so far, eleven thousand people have contributed more than three hundred thousand pounds.

Meanwhile, Banks has a troll army on Twitter set on taunting her about how she’ll lose her apartment and go bankrupt. Cadwalladr seemed dismayed when I spoke with her about it recently. But she was not discouraged. There is an upside, she said, which is that she always finds that “you can use their weapons against them.” The lawsuit would allow her to publicize who Banks is and what nefarious activity he’d been up to. “I want to make Arron Banks famous,” Cadwalladr said. “I want to make people understand.”

Elisabeth Zerofsky is a journalist based in Berlin. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine, and Harper’s. She is currently a fellow with the Robert Bosch Foundation Fellowship Program.