The public editor is no more at The New York Times. For 14 years, following the Jayson Blair scandal, a succession of public editors read thousands of reader complaints, investigated claims of journalistic malpractices, and published their findings unfiltered, naming names and calling foul when they saw fit. It’s a job few envied but most people in journalism circles paid close attention to. The editors often found themselves in disagreement with colleagues, and even with direct access to the publisher at all times, the job was never easy. But all agreed the job was a testament to the integrity of the Times. Over the last six months I’ve photographed and interviewed all six who served as public editors of the most influential newsroom in the world.

Here’s the story of the Times public editor, as told by the six men and women who held one of the most challenging jobs in American journalism:

“PICKING THE WINGS OFF FLIES” is how one former New York Times editor described the job of public editor. The painstaking dissecting and reinvestigating of the work of reporters and editors, making ethical calls on potential conflicts of interest from a reporter’s tweets to the executive editor holding a story at the request of the president of the United States is not a job for the faint of heart.

Barney Calame, the second public editor, took on the role after almost 40 years at The Wall Street Journal. He described one especially tight spot during his tenure while addressing the ethical issues raised by the reporting of a story about child pornography during the rise of webcam technology. It was a tremendous undertaking by the reporter, Kurt Eichenwald, a seasoned journalist. It focused on Justin Berry, 18-years-old at the time of the 2005 article, who had entered a dark pocket of the internet as a webcam porn star and promoter. Eichenwald documented the young man’s journey out of that world.

ICYMI: Two dozen freelance journalists told CJR the best outlets to pitch

The public editor is charged with reviewing the work of the Times’ staff, so Calame’s mission in this case was to revisit how Eichenwald reported the piece after his methods were questioned. Eichenwald misrepresented himself when he first met Berry by not revealing that he was a reporter. Later he paid him $2,000 dollars for an in-person interview.

Eichenwald said he had been acting as a private citizen to help the young man, but then would put on his journalism hat when appropriate to cover the story. The question Calame had to answer was whether that approach was ethically sound.

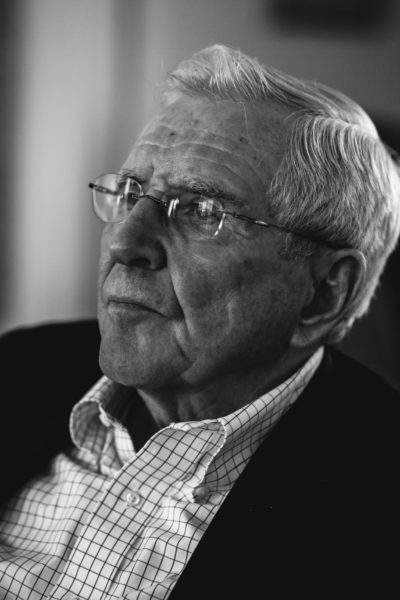

Barney Calame

Barney Calame: “You just can’t say well, ‘I’m doing this as a private citizen and then I’m going to turn and change and be a journalist.’ In that case he had contaminated the well…[You say], ‘Listen boss. I’ve been trying to help this kid and it turns out he’s a really interesting case. And I mean, I’ve gotten involved helping him and so obviously it can’t be me. But somebody should go after this story.’ And you have somebody else do it.”

Calame was getting lunch one afternoon following the publication of his first column critiquing Eichenwald, when he heard the voice of Bill Keller, then the executive editor of the Times. According to Calame, Keller walked up to him in the cafeteria and said, “Well, Calame, what are you doing this week to ream us a new asshole?” (When I asked Keller about this incident he said, “I have no memory. It doesn’t sound like something I’d have said.”)

Startled by the very public scene, Calame said he stammered and responded, “I’m just trying to do my job.”

Journalists will often tell you they went into the profession to hold the powerful accountable. But according to a recent Gallup poll, trust in the news media has fallen to a new low, with about 32 percent of Americans saying they have a great deal or fair amount of trust. President Trump, of course, has ridden and fanned the wave of anti-media sentiment.

The public editor role was created to help make the Times accountable. Some who held the position likened it to being an “internal affairs cop.” The job involved pulling back the curtain on the reporting and editing process, serving as the representative of Times’ readers. They wrote on issues readers wrote in about in letters, emails, phone calls, and tweets. It was often a contentious process between public editor and the editors and reporters. Calame faced major pushback when investigating Eichenwald’s blockbuster story, which at the time was garnering Pulitzer buzz.

Calame: “I never won a Pulitzer. I’ve been involved with stories that won, but it’s a big deal and I began to say to myself, do I really want to take this story, try to take this story down? And maybe the Pulitzer board’s not going to be affected by that, but it’s a good chance that they would be. And do I want that on my conscience? That really affected me but it was Keller’s zeroing in on me in that week [in emails to Calame and an interview with a media pundit at another paper] that caused me to pull back and say, ‘Okay, I can tolerate this.'”

Calame continued to write about Eichenwald’s reporting in a follow-up column as new information came out. He contends that he went a little soft on the handling of the story the first time around. But once the news of the $2,000 broke, Calame reported the entire controversy in great detail, as a part of his nitty gritty approach to the job.

Everyday complaints would pour in, and it was the public editor’s job, with the help of an assistant, to sift through them, investigate claims, and respond in some manner; be it in a personal reply or addressing the issue in their column or blog posts. Margaret Sullivan, who effectively transitioned the role into the digital age in 2012 by blogging and considering perspectives from Twitter, estimated about 500 responses would pour in a week.

TRENDING: ‘Thank God the brain cancer waited for the Pulitzer’

Responding to the end of the public editor era

Liz Spayd: “When I first read about the Reader Center, I wondered if that might lead into ultimately killing the public editor role. Just because it sounded as if, you know, when I looked at that language when it came out, I thought, ‘Huh, that’s interesting.’ Sounds like whoever’s doing that is certainly not doing the same role. I want to be clear about that. But they were in the space of interacting with readers, and since the public editor is pretty much defined as the reader’s representative, a little bell went off in my head. No one said anything to me. When I asked about it, I got, at that time, sort of somewhat vague answers about what it was going to be.”

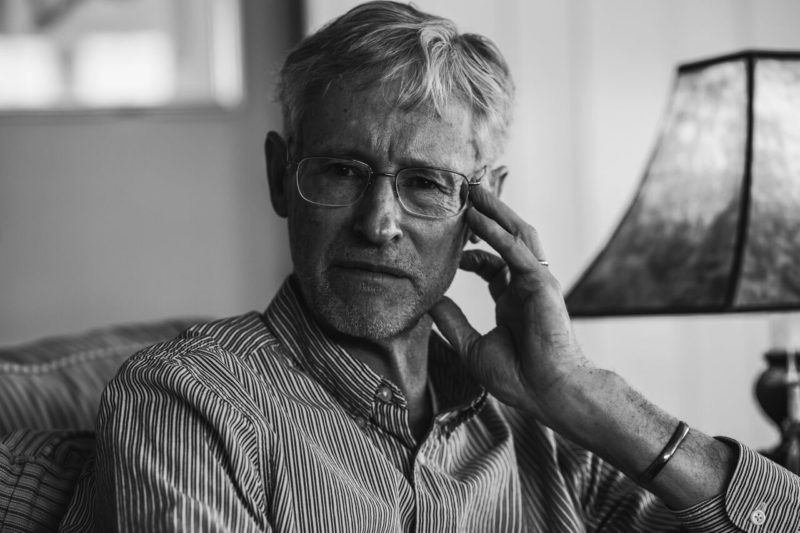

Daniel Okrent, the first public editor from 2003 to 2005, had been thinking for a while that the end might be near for the post.

Daniel Okrent

Daniel Okrent: “I’ve followed this pretty closely with various inside sources that I have … the editors wanted to get rid of it. And the publisher, Arthur [Sulzberger Jr.] said ‘No, absolutely not, we cannot get rid of this, this is important, this is necessary.’ Well, as belts tighten, you know, things change. I mean, they were saying at the time, do we want an Albany Bureau Chief or do we want a public editor? We can’t afford both. Albany Bureau Chief is an arbitrary choice. The most recent fight has been in the other direction, that Arthur wants to get rid of it, and the editors feel that they can’t. I was told this on pretty good authority at the time that they were hiring Liz Spayd.”

Calame, who was public editor from 2005 to 2007, had his doubts upon arrival. In his previous role, he had even investigated the need for a public editor at The Wall Street Journal.

Calame: “I looked into it, spent some time thinking about it, talked to people. I said I don’t think the Journal needs a public editor. So then there were people at the Journal who were throwing that at me when I took the Times job. ‘What’s this? You’re not in favor of a public editor, so now how can you be a public editor?’…I told Keller one reason I would take it is because there was one internal person, the standards editor (Al Siegal), who’s the person in the news meetings to raise questions and raising ethical questions. The public editor should be a luxury that comes after that internal person.”

The role was unique in its mandated access to Times staff. Sure, commentators can write day and night about mistakes in any particular newsroom, but they don’t have an office in the building. The public editor could tap anyone among the reporters, editors, and even the publisher. No concerned reader has that. Also to the benefit of the public editor is access to the Times platform and audience.

“A pair of professional eyes”

This role wasn’t a new one in journalism, but it was new for the Times in 2003. Jayson Blair, a once rising star reporter, had been caught making up details in several articles, including front-page stories. The Times published a 7,000 word investigation into Blair’s career in their newsroom. Howell Raines, the executive editor, and Gerald M. Boyd, managing editor, resigned. Three committees were formed to investigate the weaknesses of the newsroom.

Bill Keller, on his first day as the new executive editor in 2003, accepted recommendations including one calling for the creation of a public editor. He wrote to the staff, “The Times has traditionally resisted suggestions that we join the few dozen American papers employing ombudsmen.” Although the concept had been tried before elsewhere and there was skepticism about what it would do to staff morale, he concluded, “A pair of professional eyes, familiar with us but independent of the day-to-day production of the paper, can make us more sensitive on matters of fairness and accuracy, and enhance our credibility.”

Many people at the Times have accused me of this, and the accusation is totally fair: Not appreciating the nature of competition between news organizations. And I say you’re right, I don’t appreciate it, and I don’t give a shit.”

Okrent, as the first public editor, faced a lot of scrutiny from the staff. It was new for everyone. And Okrent was not a newspaper man. He had had a long career in publishing and magazine writing with Time.

Okrent: “Many people at the Times have accused me of this, and the accusation is totally fair: Not appreciating the nature of competition between news organizations. And I say you’re right, I don’t appreciate it, and I don’t give a shit. This isn’t about the other news organization. It’s about the reader. And what you’re telling the reader. And if The Washington Post beats you, fine, do a better job the next day. But, this was evidence to many people at Times of how I just don’t understand newspapering, and it’s true. In that sense, I didn’t understand newspapering, but I did understand newspaper reading really, really well.”

Okrent lives on the Upper East Side. The enormous lobby of his building has the feel of an old train station. Inside his apartment, his bookshelf is crammed with hardcover books, and newspapers cover the couch and nearby tables. Much of what he tends to write about are things steeped in history like prohibition in America, and baseball.

Okrent: “I figured that I would be spending the rest of my working life writing books. I wasn’t interested in a job. I was done with jobs. There were two reasons why I was interested in this. It was the Times, and I would be the first one. If it’d been any other paper, I wouldn’t have been interested. I don’t how I would’ve felt to be the second one, but to be the first one was very seductive.”

Calame was the second public editor from 2005 to 2007. He grew up in small towns in Missouri, and became a journalist when his local paper published an article he wrote when he was just 13 years old. After almost 40 years at the Journal, Barney entered the Times with a stigma of being an outsider to the Times culture and a former editor at its main competition. He had been deputy managing editor of the Journal for 12 years before his retirement.

So, you’re here. You must be dumber than you look.”

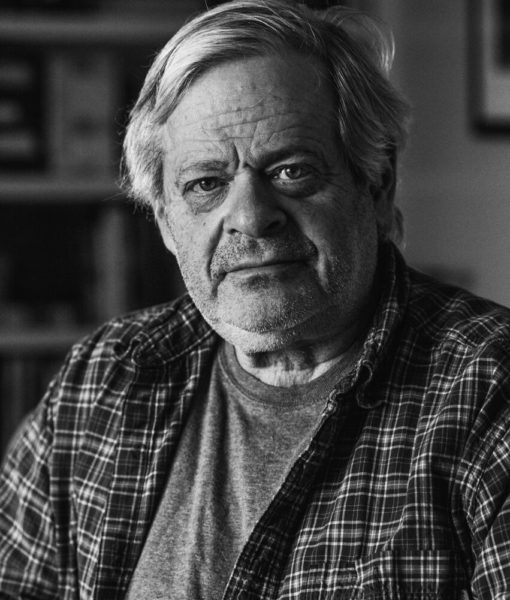

Hoyt, the third public editor from 2007 to 2010, was a long-time Knight Ridder journalist. He held multiple positions there and won a Pulitzer for his coverage of the 1972 election. Hoyt commuted in to New York City from Great Falls, Virginia.

Clark Hoyt

Clark Hoyt: “On my first day, I went in and I went up to the publisher’s office, and Arthur Sulzberger took me into this office right next to his, a little anteroom, and we sat down. I’ll always remember this, he clapped his hands on his knees and he said, ‘So, you’re here. You must be dumber than you look.’ He had a sense of humor.”

Arthur Brisbane started out in the mental health field, toying with the idea of becoming a psychologist. But after about a year treating emotionally disturbed children at Mclean Hospital outside Boston, he saw it wasn’t for him. He started work at small newspaper in Glen Cove, New York, then eventually landed at the Kansas City Times and The Washington Post before joining Knight Ridder as senior vice president. He overlapped with Hoyt, who later recommended him as a successor as public editor.

Margaret Sullivan arrived at the Times in July 2012 as its fifth public editor. Previously she spent her entire career at her hometown newspaper, The Buffalo News. She was executive editor there for 13 years before coming to the Times. I met Sullivan at The Washington Post, where she is now a media columnist.

Margaret Sullivan

Margaret Sullivan: “I had this long career in Buffalo. I did every job, including 13 years as the executive editor. I always thought, when my kids were old enough and I was nimble enough to be able to move, that a job I thought I would be good at would be either the ombudswoman at The Washington Post or the public editor at The New York Times… [The Jayson Blair Scandal] spoke to so many issues that were and still are happening in newsrooms: the effort to diversify the staff, people who find mentors, the pressure that reporters are under, the intense pressure that they’re under at places like The New York Times, the things that can go wrong, the way that in the new age you could simply be talking to your editor on your cell phone, and they wouldn’t know where you were. Which was part of what happened there.”

Okrent: “My dukes were up the minute I walked in. So anybody jabbed, I was gonna counter punch.”

Hoyt: “I think what Dan did was establish the importance of the role. That is not to be underestimated. He comes into this, never had anything like this before. [Times reporters and editors] are hostile in the extreme I think, in many quarters to the idea. They’re embarrassed because of the circumstances under which it was created. The place is in some degree of turmoil, over all this. Here comes this guy from the top and he’s going to tell them what’s what. I think that he faced a lot of hostility. Yet, he managed.”

Arthur Brisbane: “[The public editor] was kind of a mandated statutory position. You know, its origins being in the Jayson Blair scandal and then the creation of this whole new process of accountability which included a number of things, public editor being one of them. So it was kind of a remedy. It felt like a court-ordered remedy.”

How the job worked

All of the public editors were outsiders to the Times by design. Okrent built the framework of the job, including its limited term of service in the role.

Okrent: “I specifically insisted that it was not renewable, because I wanted to be able to say in my first column, as I did, that my last column will be in May 2005, and that was to make it clear that I wasn’t trying to keep my job. That was trying to say to readers that I’m not gonna be nice to the paper so that they might renew my contract. I’m not renewing my contract, I am outta here no matter what. They didn’t fight me on it; they understood what my point was. I was guaranteed independence. Nobody would see my copy other than a designated copy editor that I would approve. Nobody would see my copy until it came off press on Saturday afternoon. I didn’t do a great deal online. I was told I didn’t have to live by the Times’ style rules. I didn’t have to call anybody Mr. and Ms. They had the right to fire me. But, obviously, as I remember in the conversations with Bill, you know, how can you? If we fire the public editor, that’s really gonna be a public relations problem for us, so we really have to be confident that we’re getting the right person, or a person who is not going to do anything that’ll lead to embarrassing or humiliating us.”

Hoyt: “The contract was fascinating. I didn’t report to anybody. I think they’ve changed that since, and the public editor reports to the publisher, but at that time I reported to nobody. I could only be fired for two reasons. One of them was failing to do any work, and the other was failing to observe the written ethics guidelines of The New York Times.”

Brisbane: “I was fresh meat, and I needed to sort of figure out what was going on and how does this work. But for everybody at the Times, I was just the next public editor. So from their point of view it was business as usual: how do we deal with the public better. And what I was to learn was that really the way they deal with the public editor — a good a good sort of metaphor for it is is the legal system, litigation.”

Calame: “My view was they wanted me to come here and critique the journalistic integrity of the paper and the staff. As well as listen for reader complaints, and so I intend to do that and I’m not here to be anybody’s buddy, and I don’t think they’re going to try to snuff me out.”

Sullivan: “My whole approach was to represent the reader, and to do it in a way that was approachable, accessible, sometimes fun, sometimes very serious, but to always keep in mind that I wasn’t trying to write a journalism textbook or do anything except hold the Times to its own standards on behalf of the reader.”

Brisbane: “My workflow was to sift through stuff, and early in the week I identified my issue and then obviously reach out to to the people who were the principals whether they be external or internal, and develop my story — really just the standard reporting kind of exercise. And then begin to write. I would draft my stuff. I’d use Joe [Burgess, assistant public editor] as a sounding board. I would show what I was writing to people who I was writing about. I picked this up from Clark because Clark had done this — let’s not have surprises here.”

Hoyt: “Thursday was usually my writing day, and I would write in my study upstairs [at home], and then on Friday I had a practice that I don’t know if others have followed. I made it a point of sharing the column with everyone who I wrote about and who was quoted in it, before it was published. Then, I would say, ‘This is what I’m planning to say, and I’ll be glad to listen to you if you want to.’ So, Friday was often a day of intense phone calls, shall we say. I never regretted doing that. I always thought it was — it caught, a couple of times, errors that I might have made. I never changed a basic judgment as a result of it, but I sometimes changed wording. Given the intense feelings about something like this, I just thought it was a way that I wanted to operate, and I did.”

According to Okrent, the written column was the least amount of work. As complaints from readers would come in, his assistant Arthur Bovino would filter to an extent (some correspondence was just received in error). Then they would investigate the most pressing claims.

Okrent: “Sometimes there was one phone call, and it was settled. And it would begin with the reporter who would say, ‘Listen to this tape.’ You respond to the person who makes the most noise. And there would be those complaints coming from big corporations or universities. I mean just powerful, wealthy institutions that could hire crisis management firms, that could send a binder to me of 200 pages about what was wrong with the article. I remember one of those came from Chesapeake & Ohio. ‘Oh god, I gotta go through all this?'”

The job entails questioning the instincts and methods of reporters and editors. This was a process Brisbane once likened to someone being called into the principal’s office. Brisbane recounted a meeting he had with Investigative Reporter Ian Urbina, Deputy National Editor Adam Bryant, and National Editor Rick Berke, about a piece regarding oil companies and natural gas in 2011.

Arthur Brisbane

Brisbane: “I totally understand the reporter going into full 100-percent defense mode arguing every point. That’s what you kind of would expect somebody to do. But I figured that the editor would be, you know, 100-percent adult in the room and acknowledge where there were flaws and try to sort of essentially mediate an understanding that this could have been done differently and better. They relied for their sourcing on people who were in active ongoing disputes with the people they were criticizing. They didn’t mention this kind of stuff. And they also grossly mis-described what was going on and who they were writing about. There were a lot of problems, but I got nothing. I spent hours and hours in that room with these guys, and there were many times when I thought, ‘Why am I in this room talking these people? Why why am I giving them this much’— frankly I don’t want to say respect, they deserve respect, but, ‘Why am I giving them this much of the benefit of the doubt?’ I have zero doubts having talked to a lot of people about this. They have some serious problems —the fact they can’t acknowledge it struck me as neurotic institutionally.”

What sometimes followed a public editor’s conclusion was a rebuttal by those involved. The public editors have published letters from the executive editors, and in the case of Urbina’s story, Brisbane published a response from editors Bryant and Berke. “Everyone is entitled to opinions. But facts are facts. And the public editor’s column about our June 26 story on shale gas economics gets many of them wrong. As a result, the column’s conclusions are, quite simply, misguided and unsupported.” Urbina recalls in an email to me that Brisbane went into the meeting with his mind made up and that, “his meeting us was a pro-forma gesture so that he could the write his column with the veneer of due diligence.”

Is the Times a liberal newspaper?

About six months in, Okrent would pen his most famous column, titled, “Is the Times a Liberal Newspaper?” His opening line: “Of course it is.”

Okrent: “I’m a believer in headlines as being enticements, not summaries, but having spent my career as an editor I wrote a lot of headlines. Did I give this headline more than 60 seconds thought? I doubt it. I hit on it, I said, ‘Oh! I got it, this is perfect.’ And one thing I should mention, I did have an editor, my friend Corby Kummer, who was an editor at The Atlantic, and is still an editor at The Atlantic, he read all my columns before they went into print. So I did have somebody outside the Times. I regret I handed a weapon to people who use it unfairly. I mean, it’s been used over and over and over again without the I believe, if not subtlety, complexity of the point that I was making.”

Brisbane: “It’s a staff of New Yorkers. These are people who mostly live in the New York metropolitan area. They are highly educated, and most of them are eastern seaboard products from a kind of worldview and life experience point-of-view and come from the world Donald Trump just kicked in the butt. And they were not conscious themselves of this fact because people like you don’t get it — how the world sees you. You get what you see and it looks correct to you.”

Okrent: “I began to realize that, you know, this is a cultural issue. What’s normative to a possibly Ivy League educated, New York dwelling, upper middle income journalist? What’s normative to that person is not normative to an air-conditioner repairman in Topeka. It’s a cultural matter more than a political matter. Got an amazing response to that, ferociously negative response, but also very gratifying positive response, from the most gratifying positive response was from people on the left, from Democrats. Including one member of the US Senate, who said if I ever quoted him, he would deny it.”

Calame: “We are human, and we have these views and never mind that I spent all my life registered as an independent so that I wouldn’t be showing my personal preference one way or the other. I mean, I didn’t go as far as Len Downie Jr., who didn’t even vote, the former executive editor of The Washington Post. He was the most pure person I know, and he’s one of my heroes. I love him but I couldn’t go that far. But I think that’s where I recognized objectivity was not realistic, so I began to try to cobble a work-around, find a different philosophy.”

News coverage during an election cycle can inflame partisan groups no matter what the content, and the 2016 election was no exception. Sullivan took notice of a new “Hillary Clinton” beat established in 2013, well before she entered the 2016 fray.

Sullivan: “I did think that it was somewhat inappropriate to have someone reporting on Hillary Clinton as a beat. It was supposed to be about the Clintons, but it really was about Hillary Clinton, well before she had even entered the race. As I think I said in the piece, the word “coronation” starts to come to mind. Not to say that the coverage was all positive, but to some extent, it was giving her tremendous amounts of attention, and it also sent the message that the Times had already decided that she would be the Democratic nominee. Then, when Sanders’ campaign comes along and the Times was, especially at first, not taking it very seriously, and in fact in some cases, writing about it rather disparagingly, that combined with the fact that Hillary Clinton had been getting this coverage all along.”

In March of 2015, the Times broke the now infamous Hillary Clinton email story.

Sullivan: “When you look back on that, it’s rather stunning to think that. Yeah, they broke the story. I think now some people might say, ‘Did you immediately provide enough context about previous secretaries of state and what their email usage had been?’ Would the story have come out if the Times hadn’t written it? Yes, absolutely. Certainly. But the fact that the Times reported it on its front page, and sorry to use the old lingo, but it still matters, above the fold, clearly taking it very seriously, did set the tone. This is why the Times, I always felt, had such a weird and very difficult-to-parse relationship with Clinton. Because over here, they were giving her a ton of attention and covering her very early on. And over here, they were giving great credence to a story that in the end was possibly — probably, her undoing.”

Hoyt: “I think that even for people who love to denigrate the news media and who look upon The New York Times as this sort of bete noire of the liberal, eastern establishment, there is — underneath there somewhere, there’s a recognition of how important it is. There’s a reason why if you pick up a book in a book store it says ‘New York Times Bestseller’ on the cover. I know other news organizations may report something, but it really takes on speed when the Times reports it. It’s simply a fact of life.”

Okrent: “The biggest misconception is the belief that there is an agenda. There isn’t. It’s so hard to have an agenda at a newspaper. A newspaper comes out by accident almost. The belief that there are orders being given, that are being followed, that the editorial position as expressed on the editorial page is determinative for what kind of coverage is in the newspaper — that is all wrong. It’s simply untrue. And I without being there now, I’m sure it is as untrue today as it was then. Having said all that, I wish they didn’t have an editorial page.”

TRENDING: Headlines editors probably wish they could take back

Spayd vs. Fox News’ Carlson

In an effort to step outside the Times echo chamber, Spayd did something few Times staff have done. She entered the belly of the conservative media beast: Fox News.

Tucker Carlson, host of the Fox News prime-time news talk show Tucker Carlson Tonight, typically brings someone on the program that he can clash with. Spayd decided to go on the network, much to the surprise of viewers who later went to Twitter to voice their outrage. Their qualms included questions like, “why would a Times journalist go on Fox News, of all places?” “How could she agree with Tucker Carlson on anything?” In the interview, Carlson raises the issue of Times reporters claiming objectivity in their hard news reporting and then on Twitter making anti-Trump statements. She agreed with Carlson. The Times had sent memos to staff regarding Twitter behavior in the past, saying that, “You are a Times journalist, and your online behavior should be appropriate for a Times journalist.”

Spayd: “I am completely comfortable with my decision to go on Tucker Carlson. I know who Tucker Carlson is. I didn’t just sort of wander out there without knowing. I decided to go on because it does matter to me to get outside the liberal echo chamber. I know who his audience is, and I wanted to speak to that audience about The New York Times. I also wanted them to get a fair view of The New York Times and not a view that they would just get from the likes of Tucker Carlson. I remember saying at one point that the vast majority of journalists who walk through the doors of The New York Times every day have the highest integrity. They’re very good reporters. I didn’t care so much about Tucker Carlson. I cared about that audience that I would have the chance to speak to. I wanted to say, ‘You know what? Yeah, [those Times reporters mentioned] screwed up on one key part of this election, which is that they didn’t listen enough to this audience.’ The interesting thing about that when I got off that — I got flooded with tweets from conservatives who said, ‘You’re so brave to go on that show. I really appreciate that. You seem like you were really being honest and candid. And that was a good conversation.'”

Anonymous sources

Sullivan: “Every public editor gets involved in this whole question of sourcing: anonymous sources. That’s a big public editor subject. That’s more of a systemic issue, because what have you allowed to happen over the years? And are you holding to your own guidelines? I found that the Times had actually quite good guidelines on anonymous sources, but they weren’t always following them. There was a line in the, I guess, in the style book or someplace written down. Maybe it was in some big memo that said that sources should be given anonymity only as a last resort. Then, you’d read the paper or read the Times online, and you’d see anonymous sources in almost every story, it seemed, or in many, many stories every day. You’d say, well, gosh, that’s a lot of last resorts we have here.”

Okrent: “I’d use anonymous sources, and I came to despise them in my 18 months at the Times, and I do today. I’m not saying that there aren’t moments when anonymous sources are necessary and should be used, but the degree to which they are not necessary and shouldn’t be used, it remains just a horrible, horrible flaw in American journalism generally. It’s repulsive. And I have never thought a minute about that before I started at the Times.”

Spayd: “You know it ought to be for really a very clear reason [to use anonymous sources]. But, probably because I spent so much time in Washington, I know that a lot of very good, very good, the best kind of journalism gets published through the use of anonymous sources.”

Election 2016

Reader responses to the Times coverage spiked in the week after the election. Spayd and her assistant Evan Gershkovich responded to hundreds of readers and even called some to hear what people were feeling.

Spayd: “There was a deluge of email, for sure. Almost universally angry. No one was writing in to say, ‘Great job.’ I think that there may be some who misconstrue that these were conservatives writing and complaining. These were mostly Clinton backers writing in to complain that the Times did not prepare them for the day that they woke up to [Donald Trump as president]. And also a lot of complaints that people felt like they were not really sufficiently shown the world outside the Acela corridor. Which I completely understand. It felt like they are accurate on that.”

What also spiked after the election were subscriptions for the Times. According to an earnings press release, the Times added 276,000 new digital subscriptions in the fourth quarter of 2016, its best quarter since 2011, the year it launched an online pay model.

Spayd: “That [was] a protest vote. No question, against Trump. It’s not ‘Great job, New York Times! Great job in the election! We’re going to subscribe!’ People were unhappy with the coverage of the election. Not just at the Times, in many places. The increase in subscriptions was a response to Trump’s media bashing [and] threats to the First Amendment.”

Calame: “I believe that one of the most important things that can happen, and I believe it is going to happen, is the media will be paying more attention to Logan County, West Virginia. They’ll be paying more attention to Newton, Iowa. They’ll be paying more attention to Plaquemines Parish in Louisiana. The media was simply not informed about this whole layer of people. We’ve been through a golden era when journalists were making more money than I ever imagined when I was coming out of college in 1961. And so it was great, and I said when I retired at the Journal, I said I’m just delighted that everybody here is making so much money. But… I worry that there’s a lot more talk in the newsroom about nannies and second homes than about cooperative daycare and secondhand cars. We’re just not in touch with the whole segment of society. How many of you know somebody who has to wash their hands before they go to the bathroom because their job is such a nasty job? We have to think about it. And these people don’t buy The Wall Street Journal, but they work for people who do.”

The last public editor

Liz Spayd

Spayd arrived in the role after two years as editor and publisher at CJR, which she joined after a 25-year career at The Washington Post, most recently as its managing editor from 2008 to 2013. When I met her only a few months before her abrupt exit, her office, transparent for anyone who walks by to see into, was still pretty bare bones. Papers, pencils, and a variety of glasses were scattered on the table.

Spayd: “Margaret Sullivan gave me a pretty good sense of what to anticipate. I hope I’m not violating any confidences by saying — we had dinner and she said, ‘Well, you’ll hate this job, but you should also do it because it’s a really great job, a really great experience. You’ll be glad by the end that you took the job.’ And I feel like that’s proven fairly true. I don’t hate the job, and I’m sure she was sort of teasing me. But it’s a difficult, difficult job to do.”

At the time of Spayd’s first article on July 7, the FBI had just deemed Hillary Clinton’s email servers “extremely careless” but recommended no charges. Donald Trump was a little more than a week away from becoming the Republican nominee for president. In another week, WikiLeaks released a trove of emails from Democratic National Committee officials.

Okrent: “You know I actually, I wrote to her, and I said if you need a shoulder to cry on, I really feel for you. And this isn’t whether I agree with her positions, just to be doing what she’s doing in this environment — knowing how on edge I was, I can’t imagine. I can’t imagine.”

Attacks on the Times’ credibility came fast and furious during Spayd’s tenure. Even before the peak of the 2016 election cycle, she came with a bite in her first column about the Times’ plan to engage with readers more. She wrote, “I arrived only this past week, but from the conversations I’ve had with the leadership and with the rank and file, it’s clear that there’s a long stretch of highway between the goal and present-day reality.” She wrote about the changing media landscape and how the Times is adapting. She wrote about gender inequality at the Times and its slow pace of change. And between bigger topics, she turned in a handful of columns that landed poorly both in the newsroom and in public including a much-maligned tweet analysis. As much as the job was about the readers of the Times, she reluctantly clarifies that the audience she most wanted to reach was her colleagues.

Dean Baquet was furious. He was like out of control. But I got his attention, and hopefully he’ll think twice about what he knows about a serious investigation into a presidential candidate and not writing about it. You know? Like, what the fuck?”

Spayd: “I’m really writing internally. I mean, I write publicly but this is who I’m actually interested in. I want them to read the stuff and feel like they are convinced this is a problem or this is how ‘white’ you people are and we need to do something about that. I’ve written that strongly enough that I can get the public’s attention to make [Times’ reporters] look bad and they know they look bad [when they make journalistic errors]. I’ve tried to balance my tone. I want to be sharp. Like, with the Russia column, Dean Baquet (the executive editor) was furious. He was like out of control. But I got his attention, and hopefully he’ll think twice about what he knows about a serious investigation into a presidential candidate and not writing about it. You know? Like, what the fuck?”

Baquet fought back against Spayd through another media critic from a rival publication, Erik Wemple at The Washington Post. Baquet called Spayd’s column questioning whether the Times was too timid reporting about Trump-Russia connections, “not journalism. It is typing.” He defends the decisions he made as the story was being investigated in the months leading up to its publication after the election. Still, it’s one of the more public rebuttals of a public editor’s work from Times leadership. Asked for a response to Spayd’s recall of the reaction, Baquet said, “Liz is a fine journalist, but she didn’t understand the story, and unfortunately she still doesn’t. I stand by the comment I made then. The Times does not sit on verified claims. We publish what our reporters are able to confirm, when they confirm it.” Public editors are almost always at odds with the people they put under the microscope. Spayd contends that this was a rare contentious moment, and that her overall relationship with Baquet was good.

On Spayd’s last day, she filed her last column late morning, answered a few reader emails that had come in reacting to the news, and left early. She headed up the to Sag Harbor in the Hamptons with her partner to visit with an old friend from the Post for the weekend.

Spayd: [laughs] “I felt kind of liberated, you know? …I’ve been told by all the previous public editors that it’s a pretty thankless job where you count the days until it’s over.”

Okrent: “It was a running joke among my friends — you could wake me in the middle of the night on any moment that I was in that job and say how much longer? And I’d go ‘Four months and nine days.’ I was like the prisoner marking days off in his jail cell on the wall. It was really really tough. On the other hand, I’m really glad I did it. For a whole bunch of reasons.”

Calame: “It really was stressful to me, and my blood pressure was going out of sight at the end of the two years. My doctor had run out… he couldn’t give me any more medication. We just gotta hang on and wait for this to end.”

Brisbane: “It wasn’t that bad. I suppose the good news was I was 60 years old. I kind of had probably weathered enough things to realize, ‘This too will pass.'”

Hoyt: “I actually enjoyed it. I found it fascinating. I loved doing the reporting, talking to people in my life. Allan Siegal was just such a tremendous editor and having that relationship and bouncing stuff back and forth. I really did like it. I will say that when it was over, it was time for it to be over. I didn’t think oh, God I think I could stay another year. I was done.”

Spayd: “On the one hand I felt like it’s a real shame for the Times readers and for The New York Times itself that they decided to end that job. And for me personally I was also just as happy to move on and figure out the next chapter of my life is. As I said in my last column, I think that this role was a real sign of institutional integrity. And and when you lose that it leaves the reader feeling ambiguous about what that means. But one thing I will say is that I am not sure how much the Times really listened to what most any of its public editors were saying. Of course they read them and thought about them. I think that several of us have made this remark before. It’s hard to know how much impact any of us really had. So in that way I don’t know that [eliminating the public editor] will affect The New York Times, but what it did was give the public at least some different perspectives. When [readers] looked at The New York Times coverage, or their culture, or who makes up their news, it told the public something that they didn’t know even as top editors at The New York Times didn’t make substantive changes based on what they read. To be fair to the Times, I certainly had gotten notes from Dean at various points about a particular column and that that’s a good point. And I’m just saying in terms of like really big change that had resulted as a result of public editors, I’m not sure I can point to that.”

Sullivan: “I don’t know if I lost any sleep about it, but I certainly had times when I was pretty upset. There were also times, absolutely, when I shed tears about it. Not in the newsroom, or not very often. Maybe a couple times in the newsroom. It’s hard to describe. You’re so immersed in this world, and people take themselves pretty seriously, and it’s also a very prominent platform. I was writing on the blog three or four times a week. There would always be some intense reaction to something, and it was constant. I tried very, very hard. It was my guiding principle to try to be fair and to try to, while not going soft or easy on people, but to try to understand how that would feel to have somebody who does seem to speak for the Times in some people’s minds publicly criticizing you. I don’t think I always was perfectly fair about it, but I tried to be.”

Correction: This post has been updated to correctly identify the name of Plaquemines Parish in Louisiana, to clarify that Calame wrote two columns, each of a distinct tone, on the Eichenwald matter, and to correct the source of the “wings off flies” quote.

Andy Robinson is a Boston-based video journalist and photographer. He is currently working towards a master degree in media innovation at Northeastern University.