Tuck Woodstock wanted to help. It was late spring in Portland, Oregon, where Black Lives Matter demonstrations were growing by the night. Woodstock, who is twenty-eight, is a freelance reporter and the host of Gender Reveal (“A podcast about what the heck gender is”). At home, they were scrolling through a nonstop feed of tweets from local journalists who were covering the scene downtown. It seemed intense. “I was worried about them and wanted them to sleep,” Woodstock said. So they sent a message to a couple of reporters from the Portland Mercury, an alt-weekly: “Can I tweet for you for a night, and you can take the night off?”

The Mercury jumped on the offer—the newsroom was short on staff, having temporarily laid off half of its employees at the outset of the pandemic. Woodstock, who has written for Portland Monthly, Bitch, and the Washington Post, was hired to live-tweet from the streets for “five-ish” days. What Woodstock saw was largely peaceful, if at times chaotic; the protests had drawn the attention of the Trump administration, which deemed the city an “anarchist jurisdiction” and sent in federal officers. “I wanted to be out there every night,” Woodstock told me. The Mercury couldn’t make the gig permanent, but Woodstock kept showing up anyway, posting updates on Twitter. They sought compensation via Venmo, Cash App, and PayPal donations. And if followers didn’t use those apps? “Buy me Taco Bell,” Woodstock would say.

One night became ten, then twenty, forty. Federal officers were grabbing protesters off the streets and throwing them in unmarked vans. More people poured in to join the uprising; national reporters helicoptered from all over the country. In late August, when a drive-by rally of Trump supporters faced off against anti-racist protesters, a self-professed antifascist shot and killed a man (the shooter was later killed by federal authorities). Ted Wheeler, Portland’s mayor, traded barbs with Trump via press conference and, of course, Twitter. All the while, people like Woodstock chronicled the events, as members of an emerging alternative, independent media almost exclusively serving social platforms. Some of these protest reporters were laid-off journalists who had lost jobs in Portland’s shrinking newsrooms. There were a number of freelance podcasters and documentarians. Others were simply people who’d picked up a camera and found themselves in the right place at the right time. None earned a regular paycheck or benefits. Several were arrested or beaten by police.

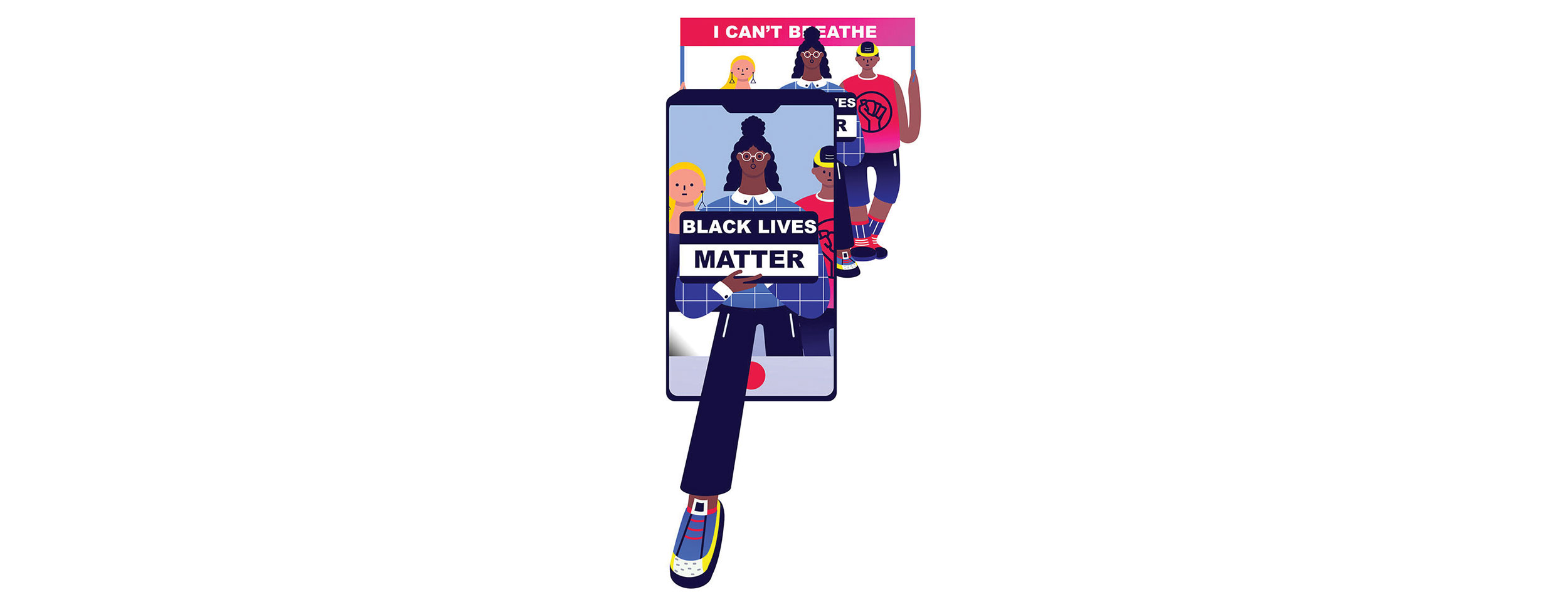

It wasn’t citizen journalism, exactly. The coverage was nonstop, attentive. Few of the reporters posting directly to social media delved deeper than what was happening on the streets, however; they seemed to be conscious that their audience didn’t require that of them. Their followers checked in to receive bits of information and short videos directly from accounts they trusted; the trust was earned through consistent presence. Allissa Richardson—the author of a recent book, Bearing Witness While Black, about activists whose journalism careers were kick-started by witnessing police brutality and providing accounts using smartphones and social networks—calls these livestreamers the “first responders” of media. “A first responder stabilizes the patient, gets the patient to the hospital, and a doctor would say, ‘I’ll take it from here,’ ” she told me. “That’s the way we have to look at journalism.”

Richardson, an assistant professor at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, first came to appreciate the power of this work in 2014, after a white police officer named Darren Wilson shot a Black teenager named Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. “It was the first time I got news from a nontraditional source,” she said. This year, as the demonstrations in Portland attracted national attention and stretched on for months, she found herself drawn to social media accounts like Woodstock’s. “I’m not learning from the highly paid reporters,” she said. Still, Richardson understood that her preferred form of coverage involved great personal risk: “People who do this kind of witnessing are putting their bodies in harm’s way. They’re opening themselves up to state violence or harassment.”

As the summer wore on, Portland became a test case for how sustainable first-responder journalism could be. By July, Woodstock was growing weary of covering a story that demanded constant focus in exchange for little money. Even more, they were starting to question what long-term personal effects their labor might have. “I’m not getting a paycheck from this. I’m not getting healthcare from this,” Woodstock said. “I’m not getting bylines. I’m just out on Twitter dot com. No one has my back for my personal safety.” At one point, they saw a federal officer fire a sponge-tipped bullet directly at the head of a protester. Woodstock was horrified. “This stuff is extremely bad for my mental health.”

Mengxin Li

As a freelance journalist who calls Portland home and often covers protests, I was enthralled by the ongoing demonstrations and found myself equally intrigued by the first-responder reporters at the scene. Encountering people like Woodstock, I found that those consistently putting themselves in danger to provide the best accounts of the scene were, by and large, the same people whose identity made them most vulnerable to violence at the hands of the state and society. They were also people who, because of their age, race, education, or identity, tended to face barriers to jobs at legacy media outlets. “I left the newsroom because I was the only person who was trans, and I was one of the only people there that wasn’t white—I couldn’t tolerate that environment anymore,” Woodstock told me. But the first-responder crowd was more inclusive. “Of the freelancers out there covering the protests on a nightly basis,” Woodstock said, “there are a number of folks of color; there is a disproportionately high number of trans people, women, and queer people.”

Woodstock was one of the few first-responder journalists in Portland whose coverage made national news: they sold a story to Bon Appétit, on a mutual-aid barbecue kitchen called Riot Ribs that became a fixture of the protests; they appeared on radio programs. Another person who broke through was Sergio Olmos, a thirty-year-old freelancer; all summer, I woke up and went to sleep to his Twitter feed. Olmos was unflinching—he captured nearly every night of the demonstrations, shooting videos of officers delivering bar-brawl punches and jump-kicking karate-style into a line of protesters with shields; he filmed clashes in which far-right groups pulled guns on leftists. The New York Times picked up Olmos as a stringer. He was thrilled by the chance—but still, he felt like an outsider. “My parents are immigrants—they came here with no guarantees of anything,” Olmos told me. “We understand that in this country, there is a need for people who are willing to do jobs and not get health insurance, but they’ll pay you because it needs to be done. We’ll take those jobs.” In August, a group of some twenty local journalists began chatting in a group-text thread, which they called the Portland Press Corps. Collectively, they agreed not to sell stories to any outlet below a certain rate. Financing their presence in the streets was paramount. “We don’t eat clout,” Olmos said, “and none of us give a shit about clout.”

Those putting themselves in danger to report from the scene were, by and large, the same people whose identity made them most vulnerable to violence.

Still, everyone felt captive to social media, especially Twitter. The hope seemed to be what it always is: that a high enough follower count might lead to a big break—maybe a job with health insurance. In the span of a couple of months, Woodstock saw their audience on Twitter grow from four thousand to forty-four thousand. That was nice, but no career-changing offer came. And in the meantime, the setup felt exploitative—Woodstock would tweet, giving away hard work, and make virtually nothing in return, which only kept rich tech people rich; social media engagement is, ultimately, worth more to the bottom lines of Jack Dorsey and Mark Zuckerberg than to any individual reporter. Not all those new followers were fans, either. “Twenty-five percent of my followers are right-wing people who are hate-following me,” Woodstock said. “There’s a really significant percentage of people who hate my work and that’s why they’re following, for some reason.”

Andrew DeVigal, a professor at the University of Oregon’s School of Journalism and Communication, told me that the Portland protests demonstrated the need to build better relationships between newsrooms and independent reporters. Olmos and Woodstock and all the other first-responder journalists were eyes on an essential story. They also had to pay rent. DeVigal pointed out how outlets, too, are at a loss when stories emerge that they’re ill-equipped to cover quickly with the staff resources at hand. Why not formalize mutually beneficial arrangements, then, with these reporters? “These independent journalists need attorneys, insurance, equipment,” DeVigal said. “These struggling newsrooms—which is everyone—can actually get great content and they can work with these on-the-ground observers that have built trust and recognition.”

“A first responder stabilizes the patient, gets the patient to the hospital, and a doctor would say, ‘I’ll take it from here.’ That’s the way we have to look at journalism.”

First-responder journalists have more to worry about than money, of course. Throughout the summer, freelancers covering the demonstrations in Portland, and elsewhere, had to justify their presence at impossible moments. When a reporter from the Portland Tribune and a photographer from The Oregonian were roughed up by police, Mayor Wheeler posted on Twitter that the incidents were “extremely concerning.” But Rachel Alexander, head of the local chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists, was incredulous. There had been numerous cases of officers chasing down and assaulting people who were documenting the protests. “Suddenly the mayor seems really concerned,” she told Oregon Public Broadcasting. “Prior to this, mostly what we documented was happening with freelance reporters.” Attorneys for the federal government said it was all a misunderstanding, since officers couldn’t differentiate who was and wasn’t a journalist. The trouble was that press credentials don’t get issued to people like Woodstock (or me), who operate independently and float around different beats. A federal judge offered a suggestion: What if the American Civil Liberties Union issued vests to journalists signifying that they were press? The idea didn’t pan out. (Instead, it raised more questions: “Why are police beating up anyone?” Miya Williams Fayne, an assistant professor at California State University, Fullerton, wondered aloud to me. “It’s a problem if you’re a journalist or not.”)

By the time fall rolled around, Woodstock was nursing a non-protest-related injury and realized that they had to take a break. The risk of getting hurt at the protests had become too great for a solo documentarian; even colleagues with institutional affiliation were plastering their heads, chests, and backpacks with press in big white letters, for fear of being attacked. “I went out there to fill a void,” Woodstock said. “Now, consistently, the crowd at protests is half demonstrators, half press, medics, and legal observers.”

Sure enough, when Woodstock stopped showing up in the streets, the donations ceased. “I was doing it as a service to people,” they said. “I could have definitely spent way more time pitching to outlets…or chasing the biggest bylines that I could. Or trying to make more money off my videos. I didn’t do that, because I wasn’t there to further my career.”

Fortunately, Woodstock has had other work to fall back on for income—the podcast, as well as a business consulting newsrooms on trans and queer equity. The first-responder journalism work served its purpose, and maybe they’ll return to the scene later, if there’s a need. (It’s a form of journalism that is, by definition, unpredictable.) Woodstock will be around to observe what must be seen, and isn’t widely shown, wherever it comes up. “The reason that I am in journalism,” they said, “is to try to center voices that, thus far, have not been adequately centered.”

Leah Sottile is a freelance journalist who has written for the Washington Post, High Country News, the California Sunday Magazine, the New York Times, and several others. She is the host of the podcast Bundyville, a two-time nominee for the National Magazine Award. She lives in Portland, Oregon.