During his time as president in the 1930s, Franklin Delano Roosevelt used a revolutionary new medium called radio to talk directly to the American people. For John F. Kennedy in the 1960s, the new medium was television. For Donald J. Trump in this decade, the new medium is Twitter, which—less than a year in—has already remade his presidency.

Depending on the hour of the day (or the minute, or the second), it can serve as a tool, a crutch, or a cudgel. He has used it to praise his supporters, to promote his administration’s agenda, and to attack those he sees as being against him—whether it’s onetime allies like Megyn Kelly, formerly of Fox News, or the head of the steelworkers’ union. It’s how he kills time in the morning while watching TV, and it’s how he gets the news cycle spinning and wages war on what he calls the “lying media.”

ICYMI: “She identified herself as a reporter. He then walked behind her and punched her”

The president’s use of a public platform like Twitter to talk directly with the American people is unprecedented for the presidency, and it raises legal, ethical, and cultural issues that have never been tackled in American politics.

The more outrageous Trump’s online comments have become, the more coverage they’ve received, creating a symbiotic relationship that has come to define Trump’s relationship with the media that covers him. But it has also boxed in a press corps that has come to simultaneously depend on and benefit from Trump’s Twitter torrent. Just because it’s being tweeted by the president, is it news? Is there a point at which the Twitter coverage gets to be too much? And is there a risk that the press corps is being distracted from more important topics?

“I think journalists have tended to over-respond to every tweet, in some ways treating them as five-alarm fires when few of them deserve to be that,” says Margaret Sullivan, media columnist for The Washington Post and former New York Times public editor. “We don’t seem to be able to show much restraint in terms of which [tweets] deserve to be ignored.”

New York University journalism professor Jay Rosen says part of the difficulty for reporters when it comes to dealing with Trump’s tweets is that the president’s use of Twitter breaks with previously accepted norms. “Political journalism is built on assumptions about how candidates will behave, like ‘all candidates are risk averse,’ so the whole idea of a campaign built on being risk-friendly is unfamiliar,” says Rosen. “But that’s what you need to start with if you have a hope of understanding Trump as president. Journalists haven’t been able to assimilate the fact that not only have trolls emerged as genuine political actors, but that the president of the United States is a troll.”

ICYMI: What we miss when we obsess over Trump’s tweets

Brian Stelter, CNN’s senior media correspondent, says that even after covering Trump for months, he is still surprised by how the president uses Twitter. “When I’ve gone on vacation and reinstalled my account and seen the president’s Twitter feed, I can’t help but be shocked by some of the things he shares,” Stelter says. “There’s a numbness when his tweets come up in your feed day after day. I find it really useful to try and step away from it, to try to remember how extremely unusual this is.”

Before he became president, reporters questioned whether Trump would continue tweeting after taking office—or whether he would be allowed to do so, because of the potential security risks (among them: his use of what appears to be an unsecured Android phone). His Twitter dependency has hardly faded since he moved into the White House, becoming an integral part of Trump’s public persona.

Just hours after his inauguration, Trump provided a hint of what was to come when he called the head of the National Park Service and ordered him to take down a tweet that a staffer had posted comparing the size of his inauguration crowd with that of former President Barack Obama (you can guess whose was smaller). “It’s a constant source of wonder,” says Sullivan. “I keep thinking he’s going to stop, that someone will get to him and say this isn’t wise, and he’ll stop, but so far that hasn’t happened.”

ICYMI: Behind the story BuzzFeed, Daily Beast, NYTimes and more didn’t want to publish

In the early days of his presidency, Trump’s Twitter use seemed almost harmless. But as the subjects of his ire have grown to include the former director of the FBI (who was heading up an investigation into his administration’s ties to Russia) and the president of North Korea (who is threatening to strike US targets), it has become a much more daunting issue. “In other circumstances, the transparency of a president who personally tweets might have been a revelation,” wrote Navneet Alang in an essay for the New Republic. But instead of relief from empty campaign statements, “we got a president who uses social media to enact revenge, spout conspiracy theories, and self-aggrandize.”

Twitter has given Trump the illusion of transparency and accessibility without his having to actually provide them.

Stelter isn’t among the journalists who consider the tweets a sideshow. “We learn an enormous amount about his mindset from his tweets,” Stelter says. “It’s a raw, shocking use of media by a president, like he’s hosting a late-night talk show—picking fights, getting even with enemies.”

Zeke Miller, Time’s White House correspondent, says there are advantages to having a president who tweets as incessantly as Trump. “The obvious one is we have a fairly clear sense of what the president is thinking,” Miller says. “The downside is that my phone is blowing up at all hours of the night. But from a professional perspective in terms of doing my job and serving my readers, it’s a net positive.”

Jack Shafer, Politico’s senior media writer, says, “This is the first time we’ve had this type of open access to the subconscious of the president.”

But there’s a paradox at play here: The steady drip of the president’s Twitter id has been accompanied by a concerted attempt to end-run the mainstream press. Trump has held dramatically fewer press conferences than any recent president—just a single solo conference as of mid-September. His administration has also shown a distinct preference for off-the-record briefings that can’t be recorded and aren’t public. And all of this has come amid ongoing complaints about “fake news” and the press, which have contributed to a far more dangerous environment for reporters in America. The U.S. Press Freedom Tracker, a consortium of media organizations including CJR, reports more than 50 press-freedom violations in the US through the end of August.

Trump’s strategy seems obvious: Discredit the mainstream media, restrict their access, then replace their reports with tweets directly from the president or interviews with friendly outlets like Fox News and Breitbart. In effect, Twitter has given Trump the illusion of transparency and accessibility without his having to actually provide them—or the accountability that usually comes with a two-way conversation with the press. It allows him to state untruths with impunity, knowing that his tweets will be widely redistributed by his followers and the media, and to dodge follow-up questions or criticism. “It’s become a partial replacement for a more traditional press corps that’s able to ask tough questions and press him with follow-ups—but it is in no way an adequate substitution,” Sullivan says.

So is everything Trump publishes on Twitter a news story, simply because he is the president? As the Times put it in a story earlier this year: “Trump expertly exploits journalists’ unwavering attention to their Twitter feeds, their competitive spirit and ingrained journalistic conventions—chiefly, that what the president says is inherently newsworthy.” Former White House press secretary Sean Spicer highlighted this problem in June when he said that Trump’s tweets should be considered official statements.

“To some degree, everything about Twitter is overplayed by the media,” Stelter says. “Twitter is not a mainstream product, most Americans are not on Twitter, and the president’s tweets are not that popular in the grand scheme of things. But that doesn’t mean what he’s saying isn’t newsworthy.”

Shafer says there should be a middle ground for journalists. “In the past, we didn’t think every presidential speech was newsworthy—when he was speaking to the Boy Scouts or to a sewing circle. It was news, but it was ‘small n’ news,” Shafer says. “I think we have to deal with every Trump tweet on its merits. There’s no obligation to cover them all, and no obligation to ignore them either . . . . I would say reporters need to go find news where it is, and sometimes it’s Twitter, sometimes it’s not.” In the larger sense, Shafer says Trump’s Twitter account “is part of the president’s publicity apparatus, and it should be considered that way, just like press releases and public appearances and photo ops.”

Miller says, “I think we all struggle with that—how much weight do you give to individual tweets. Does this tweet, and the four others before it, and this other presidential statement, and the fact that this meeting got cancelled, make it important?”

Given the kind of negative reaction his tweets often receive—from critics as well as members of his own party and even his administration—why does the president persist with this most public of mediums? People who followed Trump during his career as a New York City real-estate developer say the courting of publicity by any means is classic Trump behavior—to the point where he called tabloid reporters under an assumed name to leak stories about himself (and not always flattering ones). Trump watchers say this approach was further refined during his time as a reality TV host on The Apprentice.

In many ways, Trump was primed to take advantage of a self-promotional platform like Twitter long before it arrived on the scene in 2006. “Trump has always been hooked on recognition,” reporter Amanda Hess wrote in an analysis of Trump’s tweeting habits in The New York Times. “He is obsessed with his television ratings. His office is festooned with decades-old magazine covers featuring himself. Even negative attention can be a win; he’s thrilled to be named Time’s ‘Person of the Year’ even if the cover might evoke images of both Hitler and Satan.”

In part because of Trump’s detached approach to even serious political issues, there have been repeated attempts within the White House to curtail the president’s Twitter use. But he has said a number of times that he relishes the directness of the platform—that is, the ability to speak to his supporters without having to go through the mainstream press, and to get the kind of publicity for his ideas that he clearly craves.

“I’m covered so dishonestly by the press . . . that I can put it on Twitter [and] I can go bing bing bing and I just keep going and they put it on as soon as I tweet it out,” he said in an interview with a British MP and the former chief editor of the German newspaper Bild. “If I tell something to the papers and they don’t write it accurately, it’s really bad [but] they can’t do much when you tweet it.”

Rosen doesn’t buy the argument that Trump’s tweets are part of some elaborate media strategy. “He simply doesn’t have a sense of shame or embarrassment that normal people would have, and social media eats that kind of thing up.”

The Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University recently filed a lawsuit arguing that the president should not be allowed to block critics on Twitter from seeing his tweets. The institute argues that by having an official Twitter account, Trump and his administration have essentially created a public forum, and restricting who can participate in that forum is a breach of some Americans’ First Amendment rights.

“Though the architects of the Constitution surely didn’t contemplate presidential Twitter accounts, they understood that the president must not be allowed to banish views from public discourse simply because he finds them objectionable,” says Jameel Jaffer, the institute’s director. “Having opened this forum to all comers, the president can’t exclude people from it merely because he dislikes what they’re saying.”

ICYMI: Trump might be in serious trouble for his NBC tweets

In a similar case, a court in Virginia recently ruled against a city official who blocked constituents on Facebook. “The suppression of critical commentary regarding elected officials is the quintessential form of viewpoint discrimination against which the First Amendment guards,” US District Judge James Cacheris wrote.

Trump may also have breached another federal law by deleting some of his tweets. Caroline Mala Corbin, a constitutional law professor at the University of Miami, told NBC News that the president may have violated the Presidential Records Act, a 1978 law passed after the Watergate scandal that requires that all presidential writings be preserved.

So what is to be done about Trump and his Twitter obsession? Trump’s use of Twitter as a tool with which to attack his enemies has sparked a debate over whether Twitter itself should ban the president from using its platform. According to a number of critics, Trump’s use of Twitter to attack everyone from former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and MSNBC host Mika Brzezinski to miscellaneous followers and journalists is a breach of the service’s standards, which forbid anyone from using their account to harass others.

Venture capitalist and former Reddit CEO Ellen Pao said in an essay published on the Web platform Medium, and directed to Twitter’s management, that Trump was “using his manipulation skills and your platform to bully others, and to incite supporters to harass people—both on Twitter and in real life.” Even Jack Dorsey, the co-founder and CEO of Twitter, acknowledged in an interview that his feelings about the president’s use of the platform are “complicated.”

Minnesota Congressman Keith Ellison has called for banning Trump from Twitter, and more than 70,000 people have signed a petition asking the company to do so.

In many ways, having the president post his thoughts publicly about everything from foreign policy to the weaknesses of his enemies is a gift to journalists and political junkies. His tweets provide a real-time glimpse into the mind and mood of one of the world’s most powerful political leaders. Week-long news cycles have been built around a single update from Trump, with pundits parsing every syllable, and those stories are inevitably a traffic-generating machine for cash-strapped media outlets.

But even some of the journalists filing those stories need to question whether they are serving a larger purpose, or whether their coverage is the equivalent of Nero fiddling while Rome burns.

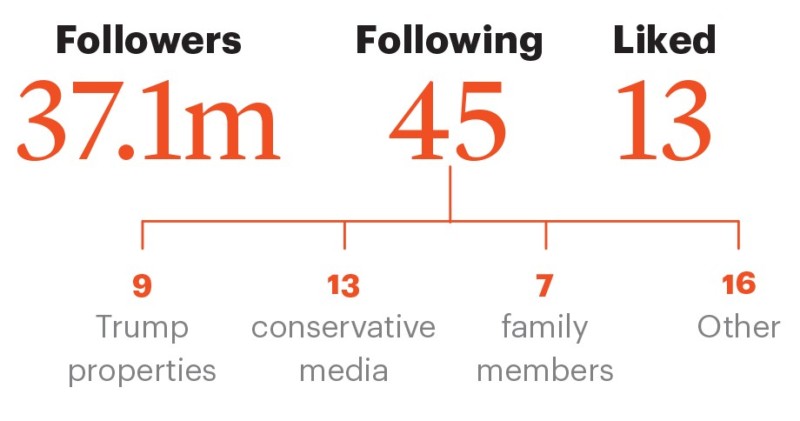

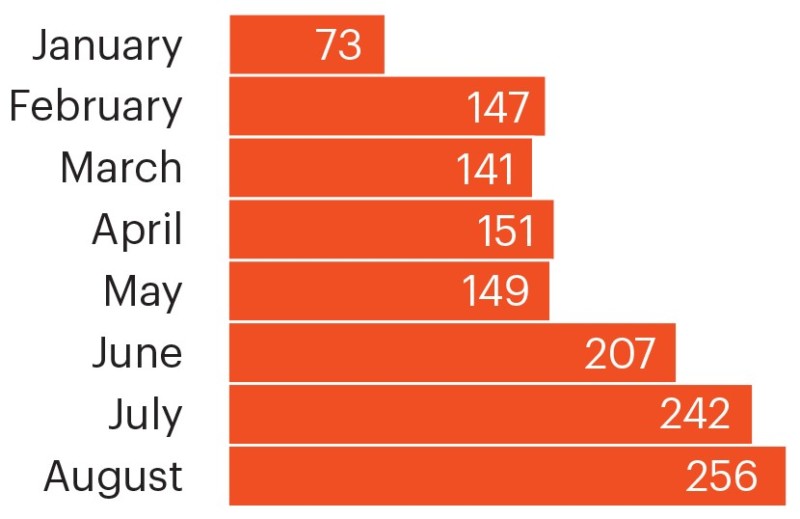

The Trump Twitterverse

Donald Trump is America’s first Twitter president. His 37 million* followers put him clearly in the Twitter elite, and his prolific tweets regularly change the news cycle. Below, a breakdown of our tweeting president.

—Pete Vernon

Most retweeted

CNN wrestling

Five memorable tweets

1. July 2, 6:21am

#FraudNewsCNN #FNN

#FraudNewsCNN #FNN pic.twitter.com/WYUnHjjUjg

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 2, 2017

2. February 17, 1:48pm

The FAKE NEWS media (failing @nytimes, @NBCNews, @ABC, @CBS, @CNN) is not my enemy, it is the enemy of the American People!

The FAKE NEWS media (failing @nytimes, @NBCNews, @ABC, @CBS, @CNN) is not my enemy, it is the enemy of the American People!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 17, 2017

3. November 9, 3:36am

Such a beautiful and important evening! The forgotten man and woman will never be forgotten again. We will all come together as never before

Such a beautiful and important evening! The forgotten man and woman will never be forgotten again. We will all come together as never before

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 9, 2016

4. May 31, 12:26am

Despite the constant negative press covfefe

5. May 12, 5:26am

James Comey better hope that there are no “tapes” of our conversations before he starts leaking to the press!

James Comey better hope that there are no "tapes" of our conversations before he starts leaking to the press!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 12, 2017

From archives: Journalist who broke Trump groping story on why others were slow

Mathew Ingram was CJR’s longtime chief digital writer. Previously, he was a senior writer with Fortune magazine. He has written about the intersection between media and technology since the earliest days of the commercial internet. His writing has been published in the Washington Post and the Financial Times as well as by Reuters and Bloomberg.