Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Neil E. Goldschmidt led a charmed life before a single news story destroyed him.

He was among the most dynamic and accomplished political leaders in the state of Oregon, with a blend of progressive and pro-development policies that, when he was governor, turned the state into a vibrant eco-center of the Pacific Northwest.

As mayor of Portland in the 1970s, he led a political revolution. He redirected funds toward a light rail system that helped revitalize the city. He gave community activists more input on local planning decisions, and he named the first African American to the city council. When he became governor in 1987, his name would become synonymous with “The Oregon Comeback” through reforms that freed the state from an eight-year recession. The Washington Post once called him one of “the best of the breed” of the country’s governors.

But Neil Goldschmidt had a secret all that time, and keeping it from the people of Oregon consumed most of his personal life.

For years he had a private detective watch over the woman with whom he shared an unspeakable past, and in all of that time she never went public with the abuse. When she did threaten to sue, he paid her $350,000 to keep silent.

She stayed quiet for nearly 30 years, until long after Goldschmidt left politics and became a powerbroker in other realms. Tall with a round face and wide smile, he remained a popular man in Democratic circles, with a flair and charisma that kept him circulating at the city’s center.

But it was Goldschmidt’s influence that led Willamette Week, an alternative weekly in Portland with a circulation of about 70,000, to look into his business dealings and discover one of the most explosive political stories in Oregon’s modern history.

The reporter, Nigel Jaquiss, found that Goldschmidt had sexually abused his teenage babysitter from 1975 through 1978 while he was serving as mayor of Portland.

For years, the rumor that Goldschmidt abused a teenage girl circulated among a few, but it was often dismissed as gossip.

Willamette Week Editor Mark Zusman, left, shakes Nigel Jaquiss’s hand after learning Jaquiss had won a Pulitzer Prize for his exposé on former Oregon Governor Neil E. Goldschmidt. (Rick Bowmer / Associated Press)

A staunch critic of Goldschmidt changed that. She provided Jaquiss the name of the victim, spurring a three-month investigation by Willamette Week in early 2004. Jaquiss spent weeks combing through public records—police reports, court documents, property records. He knocked on doors and made endless phone calls in hopes of piecing together the truth of Goldschmidt’s past.

That May, Willamette Week published what no other news outlet could prove: Beginning when he was mayor of Portland, Goldschmidt had sex with his 14-year-old babysitter on a regular basis over a three-year period.

Goldschmidt confessed to the crime immediately but never faced criminal charges because the statute of limitation had expired.

But the secret was out. It changed Oregon’s memory of a beloved governor and managed to shake up the state’s largest newspaper in the process.

Jaquiss took home the 2005 Pulitzer Prize for investigative reporting. It was the first time in Willamette Week’s 30-year history and a rare occasion for any alternative weekly to take journalism’s top prize.

After the story, Goldschmidt resigned as chairman of the State Board of Higher Education and from the Oregon State Bar. He closed his consulting practice and often retreated to his family home in France. He went from being the man everybody wanted to be seen with to the man nobody wanted anything to do with.

After decades of battling substance abuse, Elizabeth Lynn Dunham, the woman Goldschmidt had sexually abused, spent the last days of her life at a hospice. She died on January 16, 2011, at the age of 49.

More than 10 years after the Willamette Week investigation, the impact of its journalism can be felt in two ways. First, it stands as a model of blunt-force investigative might, through documents, door-knocking, and editorial courage. Second, it exposes the dangers of a monopoly paper that seemed too tied to the civic establishment it was meant to watch over. The little Willamette Week showed both the shortcomings and redemptive qualities of local newsrooms. And it surfaced the powerful place alternative weeklies still hold amid shrinking community and regional dailies.

Nigel Jaquiss, tall, thin, and soft-spoken, had an unusual résumé for a reporter. The second of four boys, Jaquiss was raised by British parents in New Harmony, Indiana. His mother had a law degree and his father was a research scientist.

After graduating from Dartmouth with a degree in English, Jaquiss traded oil in New York and Singapore for Cargill, Morgan Stanley, and Goldman Sachs. His time on Wall Street exposed him to well-connected and powerful businesspeople.

He eventually left oil trading to write a book about the subject and applied to the Columbia Journalism School, figuring it would be a good way to improve his writing.

“I wasn’t aiming to become a reporter,” Jaquiss says. “I was a big consumer of journalism but hadn’t thought much about it as a craft.”

But Jaquiss’s appreciation for journalism grew as he learned more about public records, the process of obtaining them, and the power of a well-structured story. He graduated from Columbia in 1997 and began working at Willamette Week the following year.

Jaquiss’s experience in dealing with large amounts of money, powerful people, and high-pressure situations gave him an edge over other reporters in the newsroom. He also had an editor who believed in the value of investigative reporting, and that suited Jaquiss’s new interests.

“I think investigative reporting and public interest reporting is what the guys who own the paper live for,” Jaquiss says. “That’s why they bought it, and that’s what they care about.”

In 2001, three years into his career, Jaquiss wrote an investigative story on Whitaker Middle School in Portland. The school, the worst in the state, contained high levels of radon, a colorless, odorless radioactive gas that’s known to be the second-leading cause of lung cancer deaths. There was also toxic mold.

Using inspection records and memos, Jaquiss found that the school district knew about the radioactive gas for more than a decade but never informed the faculty, students, or the students’ parents. The middle school was closed down and demolished after the article ran.

It wasn’t much later that Goldschmidt, now a prominent businessman, announced plans to lead an effort to purchase Portland General Electric, the state’s largest public utility, with backing from a private investment firm.

Jaquiss’s editors thought it might be wise to have their dogged and financially savvy reporter look into Goldschmidt’s business dealings. Jaquiss’s approach to the assignment offers lessons for any reporter trying to develop investigative chops.

In early 2004, Jaquiss picked up the phone and called then-State Senator Vicki Walker, a Democrat in Oregon known for being an outspoken critic of Goldschmidt. She had tried unsuccessfully to prevent him from being appointed to the Oregon State Board of Education in January of that year, and she seemed like a good person to ask about him.

“If anyone knows anything Goldschmidt didn’t want widely known, they would have shared it with this person,” Jaquiss says.

But Walker didn’t know of any secret business dealings involving Goldschmidt. What she did know was that the former governor had been involved in some type of affair when he was serving as Portland’s mayor in the ’70s.

Jaquiss wasn’t interested. It had long been rumored that Goldschmidt had a reputation as a womanizer, and Jaquiss wasn’t going to spend time chasing down a rumor.

The little Willamette Week surfaced the powerful place alternative weeklies still hold amid shrinking community and regional dailies.

The senator told him it wasn’t just any rumor. This one involved an underage girl, perhaps Goldschmidt’s babysitter. The senator also had documents with the name of the woman. Jaquiss asked her to send him the documents, and she did, by fax.

The six pages were for a conservatorship that had been filed in Washington County in the mid-’90s. They listed the name of a woman, Elizabeth Dunham, who appeared to have suffered from an injury. The documents didn’t have specifics about the injury, how it occurred, when it occurred, or who caused it. Still, it was a start.

Jaquiss took what he had to his editor, Mark Zusman. Like the publisher, Zusman knew Goldschmidt, and the story could have ended there. Instead, Jaquiss got the green light.

“I’m lucky,” Jaquiss says. “The guy who has been the editor of the paper is a skeptic, and fearless.”

Jaquiss began searching for every public record he could turn up with Dunham’s name on it.

“I wanted to find out everything I could about her without tipping off Goldschmidt,” Jaquiss says.

He also worried about the competition. Jaquiss had heard that a veteran reporter at the Portland Tribune, a newspaper with a circulation of 120,000 that publishes twice a week, had been tracking the same rumor, but for some reason his investigation stalled. Then there was The Oregonian, a daily newspaper with a circulation of more than 300,000 that could devote significant resources to the investigation.

“One had a mass of resources and another was ahead of me,” Jaquiss says. “I was way behind.”

He would later learn that The Oregonian had the story in its lap. It was the second time it had been given a tip about Goldschmidt and dropped the ball.

But Jaquiss, not realizing what The Oregonian knew, focused mostly on documents.

“Pretty quickly I started to figure out [Dunham] had been in Goldschmidt’s orbit and something bad had happened to her,” he says.

He pulled court records, police reports, and property records from Oregon, Washington, California, and Nevada. He turned to elementary and high-school yearbooks to track down friends of Dunham. The process took several weeks.

At that point, the documents served two purposes: They provided a list of people to interview, and they established a narrative of how Goldschmidt’s and Dunham’s lives crossed.

Property records showed that Dunham and her family lived six doors away from Goldschmidt, who was also a friend of the family.

Dunham’s mother worked for Goldschmidt as an aide when he was serving as the youngest mayor of Portland in the ’70s. Dunham, a high-school student at the time, was a city hall intern who sometimes babysat Goldschmidt’s children. Goldschmidt was married and the father of a boy and a girl. It was 1975. He was in his mid-30s and Dunham was 14.

Somewhere around that time Goldschmidt began to sexually abuse Dunham, a thin girl with wavy, chestnut hair. They would have sex in the basement of her parent’s home, hotels, and other private places. Goldschmidt would end the sexual abuse in 1978, when Dunham was 17.

The next year, President Jimmy Carter named Goldschmidt Secretary of Transportation, and when Carter’s term ended, Goldschmidt returned to Oregon. Five years later, Goldschmidt decided to leave a senior post at the Nike Corp. and run for governor.

As for Dunham, she was 25 and spiraling out of control as she tried to come to terms with what happened between her and Goldschmidt. She was drinking heavily and talking about her sexual abuse with friends. She was arrested for a DUI and scolded the arresting officer, telling him he would pay for his actions because she was friends with Goldschmidt. The arresting officer included her statements in a police report.

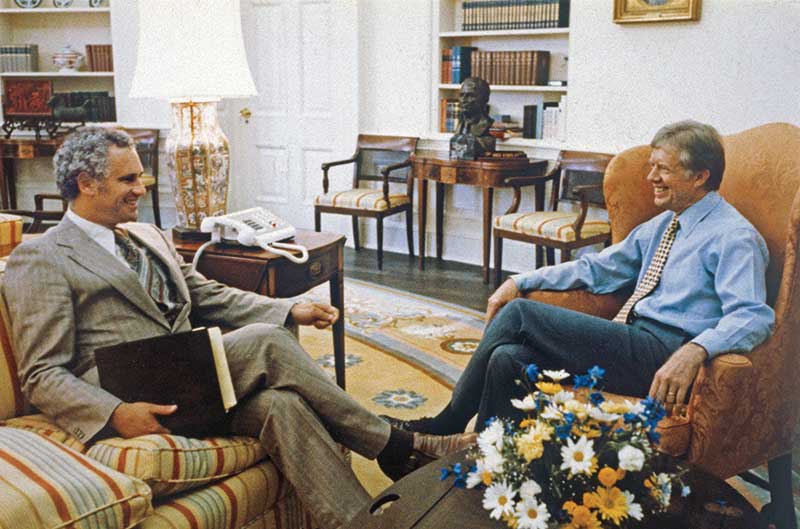

President Jimmy Carter named Goldschmidt as his transportation secretary in 1979, more than two decades before the ex-governor’s misdeeds would come to light. (Bettmann / Getty Images)

“It didn’t prove anything but it was a strange thing to say,” Jaquiss says.

As Dunham’s problems escalated, Goldschmidt sought help from Robert K. Burtchaell, a private investigator, businessman, and alcohol counselor.

Burtchaell’s job was to keep Dunham out of trouble. He tried to help her get sober, and he took care of her legal problems and paid her bills, including charges she made on a credit card she stole from a roommate.

On the surface, Burtchaell’s role was part fixer and part mediator. He scheduled meetings between Dunham and Goldschmidt in what he later said was an attempt to help Dunham gain stability.

In 1988, two years after her DUI arrest, Dunham moved to Seattle for a fresh start. She was 27 by then, and Goldschmidt had found her a job as a clerk at a law firm.

But it was a short stay. In December, she was abducted at knife point and brutally and repeatedly raped. After that, she moved back to Portland and soon was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.

A man named Jeffrey Jacobsen was later arrested for the crime, but Jacobsen’s attorney discovered that prior to the rape Dunham had been the victim of sexual assault, for which she had undergone counseling as a teenager.

The attorney asked the judge to have the counseling records submitted as evidence. The lawyer argued that Dunham was confusing Jacobsen with the man who had raped her when she was a teen. The twisted case was a turning point for Jaquiss.

“The Washington trial transcript was really strong,” he says. “It identified Goldschmidt, not by name, but it put a time frame and mapped out what I was thinking had happened.”

The year Dunham was raped in Washington, Goldschmidt was finishing his second year* as governor. He reformed the state’s workers’-compensation system and recruited several tech companies to Oregon’s Silicon Forest. The state was emerging from recession. Life was good.

In 1989, attorneys were continuing their fight to introduce Dunham’s counseling records as evidence, which if unsealed, would expose Goldschmidt. A judge allowed some but not all of the records to be unsealed. Jacobsen was convicted of raping Dunham that year.

The attorneys appealed the verdict, arguing that all of Dunham’s records should have been unsealed. With the legal maneuverings ongoing, the 49-year-old governor decided not to seek a second term. His decision shocked Democrats across the state.

As it turned out, the court appeal was denied, allowing Goldschmidt’s secret to remain buried. Though out of office, his influence never waned. He became a powerbroker in Oregon and stayed near its political center.

Meanwhile, unable to work, Dunham received a monthly disability stipend of $400. She turned to alcohol and cocaine. She was arrested nine times between 1991 and 1994.

In 1992, when Dunham was sent to prison for violating her probation after a cocaine bust, several women accused then-State Senator Robert Packwood, who had been narrowly re-elected to office, of unwanted sexual advances. One of the women was a political reporter for The Oregonian, whose editors had been aware of the harassment but failed to report it.

In fact, it was The Washington Post that would break that story and force Packwood to resign. But it wasn’t only Packwood whose reputation had been affected; Oregon’s papers had missed the story. Most of the criticism was aimed at the state’s largest paper—The Oregonian.

Two years after the 1992 Packwood scandal, Dunham finally hired an attorney and threatened to sue Goldschmidt. To head off the lawsuit, Goldschmidt agreed to pay her $350,000. The cash payments, however, were contingent on a confidentiality agreement, preventing Dunham from speaking out about her sexual abuse.

In May 2004 Willamette Week exposed Goldschmidt’s secret and, once again, The Oregonian found itself scooped on a major scandal.

Hours after the alternative weekly ran its story, Goldschmidt gave The Oregonian an exclusive interview and provided his account of the sexual abuse. He told the paper the “affair” had lasted a year. He talked about his health and his worries about how the story would impact his family, friends, and political associates. There was very little mention of the victim.

The next day, The Oregonian’s problems continued. The paper was criticized for the story and its headline, which referred to the sexual abuse as an “affair.”

Staffers at The Oregonian expressed disappointment and concern that the paper didn’t do enough to hold Goldschmidt accountable when he made his confession. The paper would, however, later devote staff to look into the scandal.

Willamette Week devoted some of its coverage, meanwhile, to finding out why The Oregonian had missed the story amid evidence that it knew of the rumors.

“Newspapers exist for a lot of reasons,” Jaquiss says. “One of them is to hold powerful institutions and people accountable, and we felt The Oregonian was a powerful institution.”

Goldschmidt’s behavior, and his 30-year effort to conceal it, are appalling enough, but The Oregonian’s soft-pedaling on the story adds an egregious twist.

Jaquiss learned that The Oregonian had received information about the sexual abuse scandal in the winter of 2003. It wasn’t the first time. He also learned that The Oregonian had first been told about Goldschmidt and Dunham in 1986.

An editorial cartoonist at the paper, a man named Jack Ohman (who, notably, won a 2016 Pulitzer for editorial cartooning), received a tip in the mid-’80s that Goldschmidt had sexually assaulted a young girl. Goldschmidt was running for governor at the time, and Ohman took the news to his editor. His editor interviewed Ohman’s source and then brought the information to other editors at the paper.

The second time The Oregonian received a tip on the abuse was in December 2003, when Goldschmidt’s former speech writer, Fred Leonhardt, provided the paper with the victim’s name, a chronology of what had happened, and the names of other people who could confirm the story.

“If I had known Nigel [Jaquiss], if I had been aware of his background and the kind of person he is, I would have gone to him,” Leonhardt says.

So why did the paper sit on the information? The Oregonian’s explanations over the years ranged from its editors simply not making the story a priority to not sufficiently following up on the tips. There was also uncertainty about the reliability of the information because the victim was wobbly on key facts, according to Oregonian editors at the time.

“We got the tip and we were slow and ineffective in following up on it,” says Sandra Rowe, then-editor of The Oregonian.

Those explanations were published by Willamette Week when it looked into who had knowledge of Goldschmidt’s secret and what actions they took.

“That was difficult, getting people to know or acknowledge that they should have done something, but we felt it was an obvious question that needed to be answered,” Jaquiss says.

As for the 1986 tip, Michael Arrieta-Walden, then-public editor for The Oregonian, wrote in a column that whether the rumor was substantial enough to track down at the time is unknown.

“Given the fragile state of the victim and her changing story . . . it’s impossible to know if the story could have been confirmed and reported decades ago,” he wrote.

It wasn’t the first time a large newspaper had overlooked a blockbuster story on its own turf, only to be outshone by a more modestly resourced competitor. Before The Boston Globe’s Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation of the Catholic Church sexual abuse scandal, a small alternative newspaper, The Boston Phoenix, was digging into the story. Weeklies don’t always have the resources to produce the kind of high-wattage investigations that bigger newsrooms can, but often enough, they manage to deliver the goods.

“The alternative weeklies can be overlooked sometimes,” says Mike Barthel, a research associate for the Pew Research Center. “It’s important to acknowledge their place in the landscape of journalism.”

Tiffany Shackelford, executive director with the Association of Alternative Newsmedia, argues that the alternative press has a more conscious focus on the communities it covers. These publications are not the papers of record, which often affords them the luxury of stepping back and spending more time on a story.

The resulting investigative stories can be as powerful as those of large dailies or regional papers.

Since 1981, The Village Voice in New York, The Boston Phoenix, and L.A. Weekly have received Pulitzer Prizes for outstanding work in criticism, feature writing, editorial cartooning, and international reporting. Willamette Week joined that list, becoming the first alternative paper to win in the investigative category. That’s the part worth celebrating.

The bleaker news is that the same forces squeezing local dailies are also punishing the alternative press. Philadelphia City Paper, San Francisco Bay Guardian, and The Boston Phoenix are no longer in print, joining dailies like the Rocky Mountain News and The Cincinnati Post.

Shackelford says the recent decline of metropolitan dailies is now putting pressure on weeklies to step in, and in many smaller to medium markets, newsweeklies are popping up. “It has been an interesting shift,” Shackelford says.

If Nigel Jaquiss and Willamette Week are a model of what’s possible, the public interest is being carefully guarded.

Ruben Vives and his LA Times colleague Jeff Gottlieb thought they had a blockbuster. For a month, the two reporters had been painstakingly chasing down a story of municipal corruption in a small California town. Now, the motherlode was about to hit.

Vives and reporting partner had surfaced information suggesting that city council members were earning salaries 20 times that of other towns in the state. They asked for city records that could help them prove it. Instead, town officials instructed them to go to Little Bear Park, to the Boy Scout meeting room. It was time to talk.

Vives and Gottlieb arrived to discover the town of Bell’s braintrust seated before them: the mayor, the police chief, the city manager, council members, and lawyers. When the reporters got their chance to speak, they decided to throw a curveball. Looking at the city manager, they asked: How much do you get paid? Apparently fearful that the reporters already knew the answer, he told them: $700,000. Then the next official was asked, and the next, each giving an amount wildly beyond the reporters’ expectations. (The city manager, it turns out, was understating things. His total compensation was a whopping $1.5 million.)

“Our eyes were popping out, like cartoon characters,” says Vives.

If the city officials had a strategy, it clearly backfired. Four of the officials who sat around the table that day ended up facing criminal charges. The two reporters ended up with a Pulitzer.

*This article originally stated that Goldschmidt was finishing his second term as governor in 1988. The author intended to write that Goldschmidt was finishing his second year as governor in 1988–he only served one term as governor. The sentence has been corrected.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.