Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

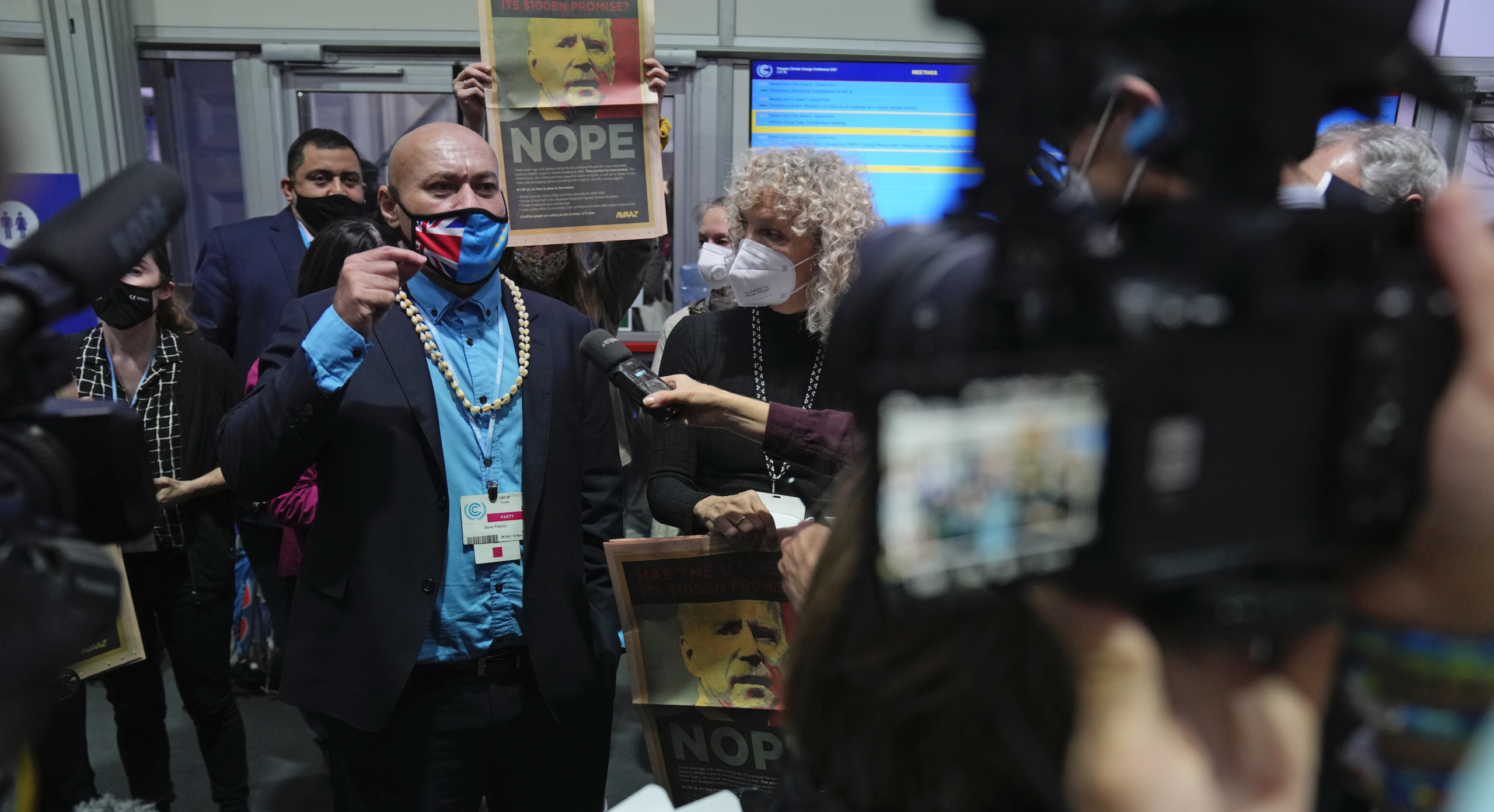

GLASGOW — Yesterday, I was leaving the media center at the COP26 climate conference when I found the exit obstructed by a media scrum. A small group of people were holding what looked like an impromptu press conference; several of them were brandishing a newspaper ad (from the Financial Times, I think) asking whether the US had kept its climate-finance promises to poorer nations and answering “NOPE,” in the style of Shepard Fairey’s Obama “HOPE” poster. So many journalists were crowded around the group that it was hard for me to hear what was being said. A Spanish journalist asked me what was going on, and I said I had no idea. He took out his phone, hit record, and thrust it over the heads of the reporters in front of us. Soon after that, a cameraman politely said “excuse me” and nudged past me without waiting for me to excuse him. He gently knocked the Spanish journalist on the head with his camera; thirty seconds later, he walked off. Eventually, the scrum atomized into separate mini-scrums as the speakers took individual questions from reporters. Security staffers seemed annoyed that we were blocking the door.

This morning, I returned to the media center before 8am, Glasgow time, and it was very quiet. Downstairs, a journalist unwittingly flirted with putting butter in his tea but was advised not to; upstairs, a handful of reporters were already perched at long rows of desks. As I took a seat, rain began to sweep over the River Clyde, which was visible through a long glass wall to my right, and patter on the flared tents that make up the ceiling. The media center is as far from the entrance to the conference venue as you can physically get (if the floor plan looks a bit like a gravy boat, security is the handle and the media center is the spout); it has a small cafe, outdoor seating, various studios and broadcast facilities, and individual toilet cubicles that are vigorously disinfected by a small army of attendants every time someone uses one. Most of the time, the media center isn’t too noisy, but it’s usually just noisy enough to make recording audio difficult. Yesterday, I tried to join a remote podcast taping in a downstairs room that shook every time someone walked over the top of it. (I was sick and tired of everything when I called in last night from Glasgow. I wasn’t actually, but I did promise to make this joke and this is my last chance.)

Previously at COP26: The People’s Summit, Extinction Rebellion, and the press

In the middle of the morning, I retraced my steps out of the media center to see what was going on in the rest of the venue. The conference is slated to conclude early this evening, but no one, not least the journalists here, expects the finish time to be respected, and the vibe this morning was “calm before the storm,” despite the looming official deadline. I stopped by a convenience store within the venue and noticed that its newspaper rack was empty; when I’d seen it empty in the evening of a previous day, I’d assumed that COP delegates must have voracious reading habits, but a cashier told me today that newspaper suppliers have actually been unable to access the venue. In a nearby auditorium, an anchor for the British network Sky, which is COP’s official media partner, stood in a brightly lit mini-studio and began a broadcast for “Climate Live,” Sky’s special channel dedicated to COP. An enormous globe hanging from the ceiling rotated slowly over her right shoulder; on the outside of the mini-studio, a screen displayed counters for degrees of warming and global CO2 emissions, both of which were ticking up. As I walked back to the media center, reporters for another British network, who had clearly just had a tipoff, planted themselves in the middle of a corridor; sure enough, John Kerry, the American climate envoy, soon strode past with an entourage. He ducked their shouted question about US responsibilities to poorer countries, then slipped into a sealed zone.

It’s no surprise, of course, but it’s struck me this week that the perspective you get covering an event of this magnitude from the inside is very different to the perspective you get observing coverage from thirty thousand feet (which is what I typically do). In some respects, being here feels clarifying, but in many other respects, I’ve found the opposite to be true—whenever I’ve knuckled down to chase a COP media story, the immensity of the rest of the conference has slipped beyond my grasp, physically and conceptually. Early this morning, with the media center still quiet, I checked in on major outlets’ topline coverage going into the final (maybe) day of the conference. I found COP on most of the homepages I checked; the story’s prominence varied, as did the angle, though variations on the “time is running out” theme were common. Being here feels like being at the center of the news universe, especially today. But for many Western news consumers, in particular, COP is just another block on a homepage, another chyron on cable news. Looking from inside here to out there, you sense an urgency gap that yawns wide.

Whatever ends up happening tonight—or tomorrow, or Sunday—the media response isn’t hard to predict: diligent reporters inside the venue (and out) will cover the agreements diligently, take-mongers will declare it an unqualified success or failure when neither is the case, major Western publications will promote the reporting and takes to the top of the news cycle for a bit, and then something else will happen and COP26 will fade into memory. The diligent reporters won’t forget it, and will doubtless work to hold countries to the pledges they did (or didn’t) make here; when they do, we will all owe them our attention. Exactly how much attention we’ll owe the next COP might still be a matter for the negotiators at this one: while these conferences are annual, governments currently are only expected to concretely improve their pledges every five years (2021 marks one of those intervals, adjusted from 2020 due to the pandemic); many parties (though not the US) think, in light of a lack of progress at this conference, that the timetable should become yearly. Not that the attention we pay the climate story should depend on this happening, of course. COPs and their pledges are good starting points for coverage if you accept our media ecosystem’s reliance on hard “news pegs.” It would be much better to see them as staging posts in a year-round story.

The subjects of yesterday’s scrum in the media center included negotiators from Ghana and Tuvalu as well as representatives from environmental organizations; they’d come to talk to reporters in a bid to pile pressure on American officials to be more ambitious as the talks conclude, including around the payment of reparations to poorer countries that have already sustained huge climate damage. Despite having been a few feet away, there were so many people between me and them that I learned most of this only later, from a report in the Washington Post. I had immediately recognized one of the speakers, though: Saleemul Huq, a long-time fixture of COP negotiations who leads the International Center for Climate Change and Development in Bangladesh. I’d spoken with him about media coverage of COPs before this one began, and incorporated his views into my first dispatch from Glasgow, on Monday.

Yesterday, as other speakers continued to be mobbed by journalists, Huq peeled away and I ended up standing next to him in the drinks line. I remembered something he’d said to me during our first conversation—that COPs as annual events have become “redundant” as news stories, given the increasing regularity of extreme-weather events all over the world—and asked him about it; the focused scrum of media interest that he’d just been a part of, I noted, isn’t really equivalent to the dynamics of the climate story outside the conference’s walls. “The conference has value, I’m not saying it doesn’t,” Huq replied. “Media people, you need a hook to report.” We paid for our drinks and reconvened in a seating area. “The climate change story is not talking about doing something at the COP. The climate change story is tackling climate change on the ground, preventing millions of people dying from climate change,” Huq said. “That’s the reality of climate change and that’s the story of climate change in the rest of the world. It’ll come to you. Because you haven’t prevented it. So get ready for it.” That’s the storm.

Other notable stories, by Mathew Ingram:

- As many news outlets cut back on publishing mugshots, Keri Blakinger writes for the Marshall Project that some states and cities “are grappling with a more fundamental question: Why do police release the images—and should they be allowed to?” The Justice Department has repeatedly refused to release mugshots, Blakinger says, arguing that there’s no public safety interest in releasing pictures that are a “lasting image of what can be one of the most difficult episodes in an individual’s life.” Several states have also stopped releasing them, and some have even banned their release. In San Francisco, the police department “only publishes arrest photos when they serve a clear law enforcement purpose—like finding a suspect or a missing person,” writes Blakinger. Corey Hutchins wrote about the negative effects of publishing mugshots for CJR in 2018.

- Ethan Porter, a researcher with the School of Media and Public Affairs at George Washington University, and Evan J. Wood, a researcher with the Department of Political Science at Ohio State University, write for the Washington Post about a study they published in the September issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences about the effects of fact-checking on misinformation on social networks. Experiments conducted with fact-checking organizations around the world showed that fact-checking does have an impact on stemming the flow of misinformation, their research shows. In four countries—Argentina, Nigeria, South Africa, and Britain—“fact checks made people more accurate, effectively leading them to reject the misinformation.”

- For CJR, Maria Bustillos interviewed Brian Bonner, editor-in-chief of the Kyiv Post, an English-language newspaper in Ukraine that was recently shut down by its owner, the Syrian-born construction mogul Adnan Kivan, amid tension with the newsroom over plans to start a new version of the paper. “Tensions came to a head some weeks ago, when Channel 7’s Olena Rotari announced on Facebook that she would be heading a Ukrainian-language version of the Kyiv Post, with its own staff,” Bustillos writes. “Trust appears to have broken down during subsequent discussions regarding the exact parameters of the Kyiv Post’s editorial independence.” Bonner said there is a movement underway to get Kivan to sell the paper to a group of former staffers who want to form an NGO.

- A senior executive at a UK fashion magazine has been suspended by the company after more than a dozen women accused him of sending sexually inappropriate messages, The Guardian reports. Max Clark—the fashion editor at i-D magazine, which is owned by Vice Media—has worked there since 2014, and also worked as a stylist for a number of high-end fashion brands such as Prada and Burberry. “Messages reviewed by The Guardian show women claiming Clark made unwanted advances towards them, with the separate alleged incidents taking place over several years,” The Guardian said. “Their claims were collected semi-anonymously via Instagram before being passed to Vice’s human resources department, prompting the company to launch a formal investigation and suspend Clark last week.”

- A survey conducted by the Reuters Institute at Oxford for its “Changing Newsrooms 2021” report shows that newsrooms are making uneven progress when it comes to returning to the office post-COVID. The report was based on a survey of 132 senior industry leaders from forty-two countries, as well as a series of in-depth interviews, and Reuters said the data “makes clear that ‘hybrid working’ will soon be the norm for the vast majority of journalists in many news organisations—with some people in the office and others working remotely.” The institute said the study also shows that the media industry is “still struggling with attracting talent and addressing lack of diversity.”

- LGBTQ employees are quitting the BBC because of how the state-funded broadcaster handles stories related to LGBTQ people, according to a report from Vice. In a “listening session” held by the network over Zoom on Monday, which the magazine got access to, five former staff members talked about how they felt “hidden” and “ashamed” during their time at the BBC, which eventually led them to quit. The most recent resignation was last week. “Current employees also talked about being ‘disappointed and frustrated’ by recent issues which have come about in the corporation,” Vice reported. The session “was organised following the huge backlash the BBC recently received after publishing an article which claimed some trans women are rapists.”

- Ko Bragg writes for CJR about hurricanes and resisting the “looting” myths that often spring up in the wake of such disasters. “News outlets had sixteen years, to the day, to consider the consequences of sensational coverage that emphasized looting beyond the realities on the ground,” Bragg writes, referring to Hurricane Katrina. “Then Hurricane Ida hit, and news outlets, drawing once more on official sources, pushed ‘looting’ back into their headlines. Two decades of debunking myths post-Katrina was seemingly for naught.” Not enough reporters openly questioned whether anti-looting squads were the best use of resources during a crisis, Bragg says, “or whether they were even effective at stemming robberies. Without those questions, reporters risk telling stories that validate expanded police details and actions.”

- Victor Pickard, a professor of media policy and political economy at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg School for Communication, and Antoine Haywood, a PhD candidate and a fellow at the Annenberg School, wrote in an essay at the Nieman Journalism Lab that public access television channels “are an untapped resource for building local journalism.” Instead of letting such channels gradually decline due to commercial market pressures, the two argued, “we should publicly fund and expand the precious communication infrastructure that access media offers… we should leverage and expand such invaluable community infrastructures before they vanish altogether.”

ICYMI: The Kyiv Post‘s Brian Bonner on why silence is not golden

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.