Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

All this week, CJR is running a series of pieces, on our website and in this newsletter, on the fog of news and propaganda that has marked the first hundred days of Donald Trump’s second term as president. Yesterday, Kyle Paoletta reported on the legal battle for transparency around Elon Musk’s so-called Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE; today, Aida Alami spoke with White House correspondents about how Karoline Leavitt, the press secretary, has made the briefing room a surreal place. You can read the piece here.

In May 2020—with the COVID-19 pandemic ravaging the US, and shortly after a white police officer murdered George Floyd, a Black man in Minneapolis, sparking mass protests that would spread nationwide—Karen Attiah, a columnist at the Washington Post, wrote a widely shared satirical dispatch imagining how the media would cover the events if they were happening in a foreign country. (“In recent years, the international community has sounded the alarm on the deteriorating political and human rights situation in the United States under the regime of Donald Trump,” it began. “The former British colony finds itself in a downward spiral of ethnic violence. The fatigue and paralysis of the international community are evident in its silence, America experts say.”) This was one of a number of pieces from the time that cast an outsider’s eye—imagined or real—over a frightening period in American history. In a newsletter in October 2020, I quoted from a piece in GEN by Indi Samarajiva, who had lived through a civil war in Sri Lanka and made the case that the US was already in a state of collapse. Many Americans were “waiting to get personally punched in the face while ash falls from the sky,” but that’s not what collapse looks like, he wrote. It is, rather, “just a series of ordinary days in between extraordinary bullshit, most of it happening to someone else.”

A lot has changed since then. (GEN, which was hosted on Medium, isn’t publishing anymore, for starters.) But Trump is back and the US is living through another frightening period, albeit with different specifics. (Attiah wrote recently that Columbia University had canceled a course she was teaching—covering, among other things, “how mass media has historically shaped our understanding of race and the global order”—as part of a broader caving to the new Trump administration; she decided to make a version of the course publicly available instead, since “this is not the time for media literacy or historical knowledge to be held hostage by institutions bending the knee to authoritarianism and fear,” and signed up five hundred students in forty-eight hours.) And cultivating an outsider perspective remains a useful lens. After Trump won in November, Joel Simon—who worked at the beginning of his career as a freelance journalist in Mexico and Central America, and went on to monitor global press-freedom issues as head of the Committee to Protect Journalists—made the case in CJR that newsrooms should learn to approach the US with the humility of a good international reporter, and that the latter’s experience would also be instructive in navigating a climate of heightened press threats.

Meanwhile, journalists watching on from abroad have shared useful insights, not only as to how their US counterparts might understand what’s going on as their country slides further toward authoritarianism, but also as to how that state of affairs might rebound overseas. On the eve of Trump’s inauguration in January, The Guardian—which, as Simon noted, has itself leveraged the fact that it is a foreign newspaper with a strong US presence to report with a perspective that differs from that of other US outlets—asked political journalists at five news organizations around the world to give their view. Fernando Peinado, a journalist at the Spanish paper El País who has written a book about Trump voters, noted the connection between Trump’s breaking of taboos and the fracturing consensus, fifty years on from his death, that the Franco dictatorship in Spain was bad, actually. Carlos Dada, of El Faro in El Salvador, said that Trump would likely give Nayib Bukele, that country’s authoritarian leader, carte blanche to continue dismantling its democracy in exchange for cooperation on migration—a prediction that has proven shockingly correct, shockingly quickly. “We look at America now and joke: Should we do workshops for our [journalism] colleagues?” Glenda Gloria, of Rappler in the Philippines, said. “It’s utterly sad.”

(András Pethő—a journalist in Hungary, where Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has ruthlessly consolidated power, including via cronies taking over independent news outlets—told The Guardian that “Americans should stop telling themselves ‘this can never happen here.’” Yesterday, on Trump’s ninety-ninth day back in office, The New Yorker published an essay by Andrew Marantz—reported, in large part, from Hungary—whose headline asked, of the US, “Is it happening here?” “In a Hollywood disaster movie, when the big one arrives, the characters don’t have to waste time debating whether it’s happening. There is an abrupt, cataclysmic tremor, a deafening roar; the survivors, suddenly transformed, stagger through a charred, unrecognizable landscape,” Marantz wrote. “In the real world, though, the cataclysm can come in on little cat feet. The tremors can be so muffled and distant that people continually adapt, explaining away the anomalies. You can live through the big one, it turns out, and still go on acting as if—still go on feeling as if—the big one is not yet here.”)

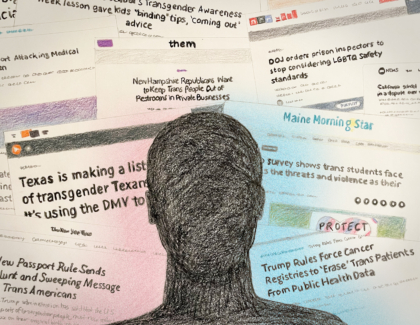

Ahead of Trump’s hundredth day in office today, I asked a number of astute journalists from all over the world to answer a slightly more media-focused question: What’s their outsider’s impression of Trump’s relationship with the press so far in his second term, and how well do they think the US media is covering his new administration? Five of them got back to me ahead of my deadline: one is a press freedom worker in DC who comes from outside the US and did not want to be identified for fear of reprisal; the others are based in countries in Africa, South America, and Europe. They shared concern about the extent of Trump’s threats to press freedom, fears about how it might ricochet to their regions, and a sense that while American journalists are doing their best, it might be insufficient in the face of bigger structural challenges to their work—a view rooted in a keen understanding of how autocrats can hit news owners’ pockets. I’ve reproduced their answers below, with light edits.

A source from outside the US who works on press-freedom issues in Washington and did not want to be identified:

As a freedom of expression defender, asking you to quote me anonymously is heartbreaking. I am a green card holder who advocates for a free press. Rumors of taking away 501(c)(3) status from civil society organizations and limiting the possibility of sending donations abroad, as well as the fear of deportation without due process, are the expected chilling effect and should by themselves already blow everybody’s mind about how far the loss of liberties has already weakened the US.

In Washington, I work with a large community of journalists from all over the world who, in past years, have found tranquility in the US, escaping from the repression of authoritarian regimes in their home countries. Many of them still have pending asylum cases. Others turned to Temporary Protected Status to bring their family members or accelerate their immigration processes. Several found a working opportunity at Voice of America [the US-funded international broadcaster that Trump is trying to gut]. For all of them, uncertainty is now the only certainty. In almost all of the cases, the media organizations or projects that supported their investigative reporting, for which they were targeted in their countries, cannot continue, as US funds to support democracy and human rights have been completely cut.

For foreign journalists in the US—regardless of legal status, whether asylum, working visa, or green card—covering the government and reporting on facts is now a dangerous task. It can mean being sent back to countries where they can be imprisoned. Therefore, many of them have decided to lower their profile, clean houses, drive Uber, or wash dishes for others.

Trump’s first hundred days in office have been devastating for the freedoms of thought and expression in the US and for press freedom worldwide.

Moussa Ngom, head of La Maison des Reporters, an investigative outlet in Senegal:

The relationship between Trump and the press seems chaotic, viewed from here. One could say that it was a foreseeable situation in light of his very negative past rhetoric about the press, but nothing could have predicted his current excesses in his crusade against the press (the refusal of accreditation, discrimination between favorable media and those he judges to be opposed to his politics, the reprisals against the Associated Press). None of this augurs well and also serves up a spectacle that could be used by undemocratic presidents in Senegal and other countries in the region—like Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, where the repression of the media is very active at the moment—who might give the example of restrictions imposed on the American media to reinforce their own repression.

The media’s coverage of Trump seems correct, as I see it. It just isn’t what a leader who is resistant to criticism desires in terms of positive representation.

Branko Brkic, leader of Project Kontinuum and founding editor in chief of Daily Maverick in South Africa:

Most editorial rooms have covered the excesses of Trump’s first hundred days well and have adequately responded to the torrent of muzzle-velocity action. Together with the judiciary, the Fourth Estate stands tall when other estates have failed or parts have been incapacitated.

It is striking, however, how much the Second Age of Trump has almost made the quality of covering his presidency irrelevant—reporters’ work is playing second fiddle to the relationship between Trump and the owners of media corporations.

Once the history of this weird period we’re navigating gets to be written, Jeff Bezos’s decision, as owner of the Washington Post, to stop the newspaper’s editorial pages from endorsing Kamala Harris will be seen as the move that changed everything. It was a first moment of palpable fear being expressed by a true leader from the business elite. (I would not count the LA Times owner Patrick Soon-Shiong at the same level of consequence.)

We as the media have only soft power to wield, and fear is the most potent venom that dissolves it. Trump smelled that tear in our continuum and went straight through it—and many corporate owners surrendered. Not only have ABC—and now likely CBS, too—created terrible precedent [by settling defensible lawsuits brought by Trump or, in the latter case, reportedly moving in that direction], they have also weakened the entire structure of the media’s edifice. (We are also witnessing Trump’s demolition of the White House Correspondents’ Association and the introduction into presidential coverage of an entire cohort of pretend-reporters from the right-wing media.)

Will the remaining giants’ resilience be enough to hold the media’s structural integrity? Only one way to find out, but they have their job cut out. What is truly frustrating is that most of that combat may have to happen outside newsrooms, in corporate offices and courts. If there’s one thing I’m certain of, it’s that journalists will keep doing an excellent reporting job—and it may not be enough. Just ask Bill Owens from 60 Minutes.

Patrícia Campos Mello, editor at large at Folha de S.Paulo in Brazil:

Trump has refined his press-bashing skills. The current administration is much more effective in creating a favorable information ecosystem. The White House has normalized hyperpartisan websites, podcasts, and YouTube channels, and gives them friendly access. Simultaneously, it is making it more and more difficult for professional media outlets to do their jobs—excluding the AP, changing the White House pool rules, overpopulating the press briefings with friendly pseudo-journalists. But his most effective weapon is threatening the cash flow of media businesses. With the weaponization of the Federal Communications Commission headed by Brendan Carr, controllers of a few networks and publications are pressuring journalists not to be so hard on Trump. Not to mention the anticipatory obedience of a few other outlets. So yes, press-bashing is back, but in a new and improved version. Name-calling is still part of it, but he is going after the wallets of the controllers of media outlets. And we know that all this is being closely observed by far-right leaders around the world. They will follow the Trump playbook, just like they did in his first administration.

Regarding the coverage: I think the publications learned a lot from the mistakes of the coverage of the first Trump administration. They are being way more careful in contextualizing statements and not amplifying smoke screens. But there is a challenge: manpower. All media have been downsizing, and there aren’t enough journalists to cover the avalanche of executive orders and decisions that Trump makes. The “flood the zone” strategy really does work.

Marco Sifuentes, founder of the Peruvian news site La Encerrona, who is based in Spain:

Trump has a dynamic with the press that we Latin Americans are well aware of. On the one hand, he subdues or discredits the mainstream media. On the other, he champions small populist outlets that make no secret of their sympathy for the regime and serve to steer press conferences toward the government’s interests. This is Latin Caudillo 101.

But Trump has another very distinctive characteristic. He uses the twenty-four-hour news cycle like no one else. It’s a machine gun of controversy. The media hasn’t finished presenting each issue, much less analyzing it, and he’s already moved on to the next. It’s Steve Bannon’s infamous concept of “flood the zone,” applied by someone who has been given the actual power to flood everything. And who enjoys doing it.

I don’t envy the American media. No one is capable of juggling so many little balls in the air. But they’re going to have to come up with an effective solution that allows their audiences to be able to assimilate and process this situation. And be aware of what’s really happening, beyond the sound and fury. Otherwise—and take this from someone recognizing a very familiar pattern—what’s coming is a third term.

Other notable stories:

- Yesterday, The Atlantic published a story based on interviews that it landed with Donald Trump—the result of an on-again, off-again process during which Trump publicly attacked the magazine and the reporters working on the story (and may have pocket-dialed one of them in the early hours of the morning after attending a UFC event in Miami). “In private, Trump often plays against the bombastic persona he projects in larger settings,” The Atlantic reported, adding that he launched “a charm offensive” directed mainly at Jeffrey Goldberg, the magazine’s editor. Among other things, Trump seemed to have media owners on his mind: he praised Bezos as having been “100 percent,” and speculated that Laurene Powell Jobs, The Atlantic’s owner, might give up on the magazine. (“At some point they say, No más, no más.”)

- For Vanity Fair, Rebecca Sananès explores how podcasts are becoming television, thanks mostly to YouTube, where shows that would in the past have been audio-only—including hits hosted by journalists like Ezra Klein, of the New York Times—are finding big viewerships that want to watch along as well. “For years, podcasts spread by word of mouth—one AirPod at a time. Loyal, niche, and hard to scale. But with video in the mix, YouTube’s algorithm kicks things into high gear,” Sananès writes. “The life cycle has completed itself: Video killed the radio star. The radio star became a podcaster, the podcaster launched a YouTube channel, and YouTube became television.”

- New York’s Charlotte Klein profiled Semafor, which launched in 2022 promising to serve the “two hundred million people who are college educated, who read in English, but who no one is really treating like an audience”—but has ended up being “quite different,” with a narrower target audience of “a select group of opinion leaders” and “a bare-bones newsroom” built around high-profile reporting talent. “Semafor today presents an interesting proposition,” Klein concludes, describing it as “a media outlet geared toward the powerful, hosting events with all the traditional trappings of power, minus the people across town who actually wield it.”

- On Sunday, the storied British newspaper The Observer printed its first edition since the digital startup Tortoise Media controversially acquired it from the trust that owns The Guardian; James Harding, the Tortoise founder who is now The Observer’s editor in chief, channeled a predecessor in describing the paper as being “roughly designed as trying to do the opposite of what Hitler would have done” and noted that it has upgraded its quality of newsprint. (Press Gazette has more.) On Friday, the paper launched a dedicated website for the first time. It will eventually be paywalled.

- And Forbidden Stories, a Paris-based group that aims to continue the reporting of journalists who have been murdered or otherwise silenced, is out with the Viktoriia Project, a collaboration, involving outlets including the Post and Le Monde, investigating the case of Viktoriia Roshchyna, a Ukrainian reporter who disappeared into the Russian carceral system and was declared dead last year. In February, her body was repatriated to Ukraine showing signs of torture and with missing organs.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.