Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Earlier this week, New York magazine unveiled its latest cover, which splashed a close-up illustration of Rupert Murdoch’s face. If this was not Murdoch’s first magazine cover in his long career of media moguldom, the occasion, this time, was the first excerpt from a forthcoming book making the case that his career is ending: The Fall: The End of Fox News and the Murdoch Dynasty, by Michael Wolff (of Trump-book-and-attendant-controversy fame). Salacious tales from the book, several attesting to recent Murdoch misjudgments, have circulated in the press, as have calls to take them with a grain of salt since Wolff may not be the most reliable narrator. Wolff, for his part, has been insistent about his book and its thesis. Asked by Vanity Fair whether “transformational change” was around the bend for Murdoch’s businesses, Wolff countered, “We’re here. This is unfolding now.” On Wednesday, at a tony book party, Wolff mounted a staircase and offered “good news” to those who fear the permanence of Fox: “The one man who holds it all together,” Wolff said, “is ninety-two years old and on a slippery slope.”

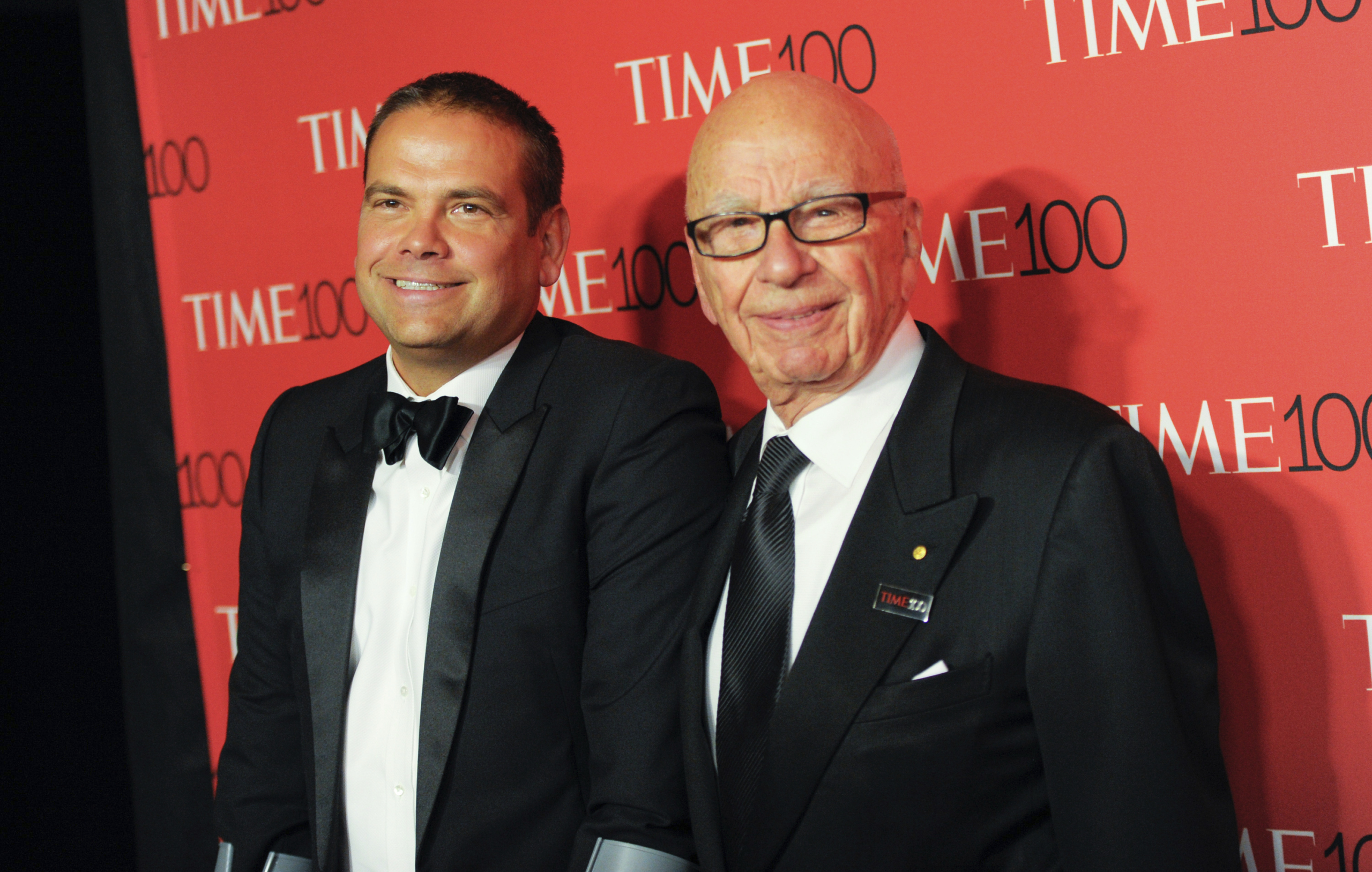

The next day, Murdoch announced that he is stepping down as chair of Fox and News Corp, his media conglomerates. (Wolff’s British publisher wasted no time in branding his latest tome “the book that brought down Rupert Murdoch.”) Some of the internal reaction to the news had an air of finality. (“I congratulate my father on his remarkable seventy-year career,” Murdoch’s son Lachlan, who will now formally take the reins of the family businesses, said.) But in a note of his own, Murdoch, who will transition to become chairman emeritus of both companies, made clear that he is not fully leaving the stage. “I can guarantee you that I will be involved every day in the contest of ideas,” he wrote, after outlining, grandiloquently and with exquisite hypocrisy, how “elites” are conspiring to end freedom of speech. “I will be an active member of our community. I will be watching our broadcasts with a critical eye, reading our newspapers and websites and books with much interest, and reaching out to you with thoughts, ideas, and advice. When I visit your countries and companies, you can expect to see me in the office late on a Friday.”

Coverage of the announcement channeled these competing senses of finality and irresolution. (It also offered no shortage of references to Succession, the HBO comedy-drama about the power struggles of an identifiably Murdochian media dynasty.) Many news stories and columns read almost like obituaries. (Murdoch “seems to have engineered a scenario in which he gets to read his obituaries before he dies,” the Fox critic Matt Gertz wrote.) But they also speculated as to why Murdoch is stepping down now, and what it all means. Is he ailing? (In his note, Murdoch described his health as “robust”; the NPR Murdoch-watcher David Folkenflik said he hasn’t heard “anything about an immediate health crisis or scare but it doesn’t mean that is not front of mind.”) Too old? (Since Fox botched its defamation defense in a case over Trump’s election lies, there have been whispers that Murdoch has lost a step; Brian Stelter, himself the author of a forthcoming book on Fox, wrote yesterday that he was struck, in researching the case, by how “passive” Murdoch seemed.) Another Murdoch expert, Jim Rutenberg of the New York Times, reported that Murdoch may have wanted to step aside before visibly losing a step, as a projection of strength. The most plausible explanation (which doesn’t exclude the others) is that Murdoch is keen to finesse the handover to Lachlan, his chosen heir, while he is still alive.

Indeed, other commentators doubted that the announcement really means much at all. Lachlan was already running many day-to-day operations; the mood music out of Britain and Australia, where Murdoch’s empire is also concentrated, suggests that he is still seen as very much in charge. Per Rutenberg, Fox insiders are talking only of a “semi retirement”; per Stelter, Murdoch himself has said in the past that he planned never to retire and that, if he did, he would “die pretty quickly,” an outcome he surely isn’t trying to hasten. Jack Shafer, of Politico, dismissed “the Rupert Murdoch retirement myth,” arguing that he would never willingly give up his power and that he could easily just unretire in future, performing what one of his British editors might have called a “reverse ferret.” To reach for another animal metaphor that I’ve applied to Murdoch before—this one from Australia by way of the UK—the timing of the announcement could even have been a “dead cat” tactic, designed to distract from Wolff’s book. (Okay, maybe not—but the announcement certainly knocked the book down Google’s search rankings, and the notion is, at least, less of a stretch than claiming that the book brought down Rupert Murdoch.)

To simplify the terms of the debate here: Is Murdoch still firmly in control, or is he losing his grip? In some ways, this mirrors a longer-term debate around Murdoch that I wrote about last year, concerning the extent of his influence: Does he make the political weather, or does he merely react to it? I argued that both things are true in a sort of equilibrium: Murdoch does shape the political landscape, but he also tracks public opinion and adapts his stances accordingly; in other words, he is very powerful, but his power has limits. As I see it, something similar is true of the retirement debate. Murdoch’s power has long been informal—a whisper in a prime minister’s ear, in lieu of ever being elected to anything—so a formal shuffling of titles in his businesses clearly isn’t the whole story. And whatever drove the timing, it wasn’t accidental. At the same time, it’s possible to see—in his businesses’ recent high-profile missteps; in his age; even in Wolff’s anecdotes, if you’re inclined to trust them—that his control is not total.

The same can be said of his succession (small s) planning. If yesterday’s announcement formalized Murdoch’s clear wish that Lachlan inherit the farm, that decision is not his alone to make; for now, Murdoch controls the trust governing his family’s stake in its empire, but upon his death, his four eldest children—Lachlan, but also James, Elisabeth, and Prudence—will have an equal say in determining its future. There has long been speculation that Lachlan’s siblings could unite to oust him; a Wall Street analyst once told Lachlan’s biographer that it’s “fair to assume Lachlan gets fired the day Rupert dies.” Following yesterday’s announcement, several prominent media-watchers predicted that the empire will end up being stripped and sold for parts. As Succession (big S this time) illustrates so deftly, dynasties often center around another great, yet tragically limited, source of power: the dominant, brilliant patriarch who can’t corral his kids or strengthen their shoulders enough to bear his legacy.

For now, we shouldn’t expect to see much change at Murdoch’s businesses; indeed, both sides of the retirement debate preach short-term continuity, either in the form of Murdoch’s continued personal dominance or Lachlan taking meaningful charge but ruling in his father’s image (or worse). For all that pundits cast yesterday’s news as either seismic or insignificant, it wasn’t really either; it should be seen, rather, as one more step down a longer road. (“Today was a season finale of Murdoch’s Succession, not the series finale,” Stelter said yesterday. “In fact, it might have been just a mid-season finale.”) Where that road goes remains an open question—but for now, I probably side with those who foresee the end of Murdoch’s empire as an empire, even if its component parts survive in something like their present form. Death is a significant, if not necessarily total, check on one’s power. But we’re not there yet.

If Wolff might be right that Murdoch is holding Fox together in its current form, I have never seen the network and the harms it has caused as a pure expression of one man’s id; the passions to which it caters—sometimes, apparently, to Murdoch’s personal distaste—will outlast the owner. Wolff’s titular reference to “the end of Fox News” strikes me as questionable, whatever you think of his reporting. His reference to the end of the family dynasty is less so, even if Murdoch’s retirement announcement is not final proof. Kyle Pope, CJR’s editor and publisher, once said, of Wolff’s Trump books, that “every era gets the Boswell it deserves.” Every media mogul, too.

Other notable stories:

- Boston University is conducting an “inquiry” into its Center for Antiracist Research, an institution launched in 2020 and led by the scholar and public intellectual Ibram X. Kendi, following complaints about its workplace culture and management of grant funding. The center recently executed significant layoffs amid a strategic pivot. The Emancipator, a digital outlet launched by the center and hosted by the Boston Globe, is thought to be unaffected by the cuts; the Daily Free Press, a student paper at BU, has more.

- In media-jobs news, Manu Raju will begin hosting the Sunday edition of CNN’s Inside Politics this weekend, taking over from Abby Philip, who moves to a weekday prime-time slot. The Intercept added Adam Gunther and Michael Mann to its newly formed board of directors. And Christopher Beha is stepping down as editor of Harper’s to focus on other writing projects; Christopher Carroll, a senior editor at the magazine, will succeed him.

- Recently, counter-terror police at an airport in the UK detained Matt Broomfield, an independent journalist who has worked in a Kurdish-controlled region of Syria and is now based in Serbia, and questioned him for five hours, including by asking whether he considers his reporting to be “objective.” Broomfield was freed without being arrested, but police confiscated his devices and have yet to return them. The Guardian has more.

- In France, fallout continues after the authorities hauled in Ariane Lavrilleux, an investigative journalist who has reported on classified documents about Egypt’s misuse of French intelligence, for forty hours of questioning this week. Yesterday, officials closed in on a former defense official suspected of leaking to Lavrilleux. And, as press-freedom groups loudly condemned Lavrilleux’s treatment, the French government stayed silent.

- And the Times columnist David Brooks was widely mocked online after tweeting that a meal that cost him seventy-eight dollars at Newark Airport is the reason “why Americans think the economy is terrible.” The restaurant at which Brooks dined pushed back in a Facebook post, claiming that Brooks spent most of that money on drinks. It is now serving the “D Brooks Special”—a burger, fries, and whiskey for under eighteen dollars.

ICYMI: Which way will the Supreme Court lean on the government talking to the platforms?

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.