Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

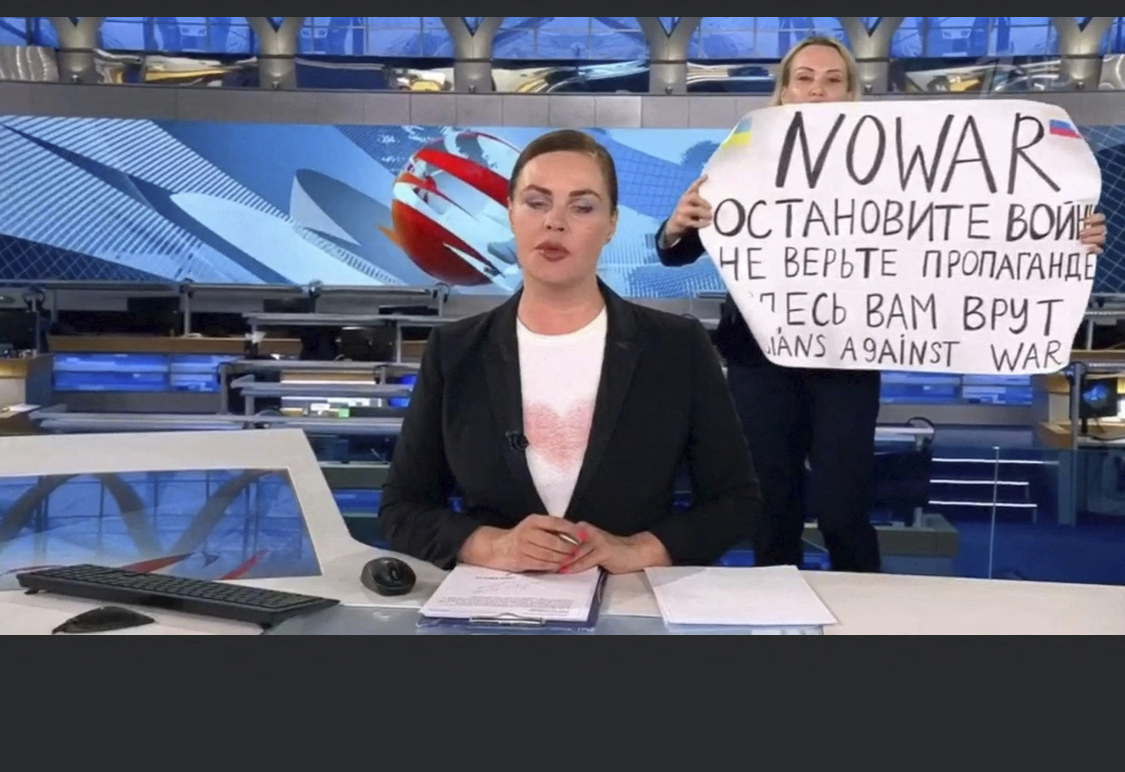

One week ago, Marina Ovsyannikova—a producer at Channel One, part of the Russian state-TV apparatus that has been a key vector of Vladimir Putin’s lies about his invasion of Ukraine—burst onto the set of an evening news show and held a sign over the anchor’s shoulder. It was topped by the English words no war, scratched between drawings of the Ukrainian and Russian flags, and continued, in Russian, “Don’t believe the propaganda, they are lying to you here”; Ovsyannikova also tried to talk over the anchor before the shot quickly cut away. Before making her stand, Ovsyannikova recorded a video message that was later made public. “I am ashamed that I let the Russian people be zombified,” she said in the video, before calling on her fellow Russians to join her in protest. “They can’t jail us all,” she said.

Ovsyannikova’s bilingual protest, aimed explicitly at both domestic and Western audiences, quickly succeeded in making headlines around the world. Concern spread, too, for her well-being—reports circulated that she had been detained and faced prosecution under a new law that harshly criminalizes antiwar speech (including the word “war”)—but by Tuesday night, she was freed, having only been fined around three hundred US dollars for calling for protests in her video, with no extra punishment for the TV stunt itself. Ovsyannikova told reporters outside court that she had been interrogated for more than fourteen hours and denied a lawyer. She has since sat for interviews with a range of major international news outlets. On Wednesday, she told Reuters that she remained “extremely concerned” for her safety; on Thursday, she told France 24 that her young son has accused her of “destroying” the family’s life together, but that she thinks he will come to understand in time. Yesterday, she appeared on ABC’s This Week, where she started speaking in English before switching to Russian because it is “a great language of Pushkin and Tolstoy.” She continued, via a translator, that her “dissatisfaction with the current situation has been accumulating for many years.”

ICYMI: The Future of Local News Innovation Is Noncommercial

Ovsyannikova has tendered her resignation from Channel One. While her protest was uniquely visible, she’s not alone—as the BBC put it last week, state-aligned Russian TV channels have recently been hit by “a quiet but steady stream of resignations.” Zhanna Agalakova, an anchor for whom Ovsyannikova once worked as a writer, reportedly also quit Channel One; Lilia Gildeyeva and Vadim Glusker reportedly left NTV, while Maria Baronova, a former top editor at RT, resigned in the days after the invasion and has herself since spoken out about her departure in international media. VGTRK, the state-TV holding company, is rumored to have lost staffers, too, with Denis Kataev, of the banned independent network TV Rain, reporting in The Guardian that many more are considering their futures amid a “nasty” internal atmosphere. “This is a new feeling for people who work in these strict, pro-government places,” Kataev wrote last week. Ovsyannikova’s protest, he added, will likely “go down in the history books,” as both a radical act of dissent and “a revolutionary development for TV in Russia.”

Gildeyeva, of NTV, didn’t only quit her state-TV job, but fled Russia altogether. She, too, is not alone. Even prior to the war, independent reporters had been forced to leave Russia as Putin intensified a clampdown on press freedom; since the invasion, the clampdown has intensified—not least via the new speech law—and so, too, has the journalistic exodus. According to Agentstvo—an investigative site that was born from the ashes of Proekt, which Putin outlawed last year, and itself now operates out of neighboring Georgia—at least a hundred and fifty journalists have left Russia since the invasion, with many heading to Georgia, Armenia, Serbia, or Turkey given those countries’ relative openness to Russian nationals. Last week, The Guardian’s Pjotr Sauer and Ruth Michaelson met with reporters exiled in Istanbul. Sonia Groysman, of TV Rain, said that she and her colleagues wanted to continue working after Putin blocked their network, only to learn of an impending raid on their offices. At that point, she says, “it was game over.”

The post-invasion exodus has been much broader than just journalists, with Russians from across civil society choosing to get out. Writing for the New York Times last week, Sophie Pinkham compared the flight of Russia’s modern liberal intelligentsia to the departure of dissident émigrés in the Soviet period, noting that while the West (not to mention Western media) was often keen to welcome the latter and help spread their ideas, the former are running into the effects of visa restrictions, financial sanctions, and generalized anti-Russian sentiment. Yesterday, The New Yorker published a big piece, headlined “The Scattering,” by Masha Gessen, who relocated from Moscow to New York eight years ago amid official threats to her family. Gessen writes that it is now impossible to imagine returning to Moscow—“my city”—and that even “if I did about four out of every five people I knew, well or at all, would be missing.” Gessen, too, observes a difference from the Soviet era. “The old Russian émigrés were moving toward a vision of a better life; the new ones were running from a crushing darkness.”

In 1970, Albert O. Hirschman, an economist, published Exit, Voice, and Loyalty, a book that would become influential in social-scientific circles. Hirschman’s argument is multifaceted and rooted primarily in market dynamics, but its basic concepts, in particular, are more broadly applicable—those who are dissatisfied with a given status quo have two main choices: leave (“exit”) or speak up (“voice”). The situation for journalists in Russia right now shows this choice at work again, as well as the complex interplay between the options. In the face of rising domestic threats, some independent outlets have relocated many of their staffers without knowing what to do next; others—the Latvia-based Meduza, for example—already set up shop outside of Russia, and are using that external base to continue to broadcast uncomfortable truths into the country, at least to those Russians able to circumvent official Web blocks via VPNs and other workarounds. Novaya Gazeta, an independent newspaper that is still based in Russia, recently curtailed its coverage of the invasion to protect its staff, but has continued to cover antiwar dissent. Last week, it ran a front-page image of Ovsyannikova’s protest, but with the word “war” pixelated. The paper, Meduza’s Kevin Rothrock noted, “is shredding Kremlin censorship by obeying it”—an act, he added, known as “malicious compliance.”

Ovsyannikova used the full extent of her voice and does not plan to exit Russia, even though she could yet face harsher punishment for her TV protest; donors have gathered the funds for her to flee, and France has offered her asylum, but she has refused. She sees staying put as a question of loyalty as we would commonly understand that term—even if, in Putin’s Russia, it has come to require the propagandistic whitewashing still practiced by many of Ovsyannikova’s former colleagues. “I am a patriot,” she explained on ABC yesterday. “I want to live in Russia. My children want to live in Russia. We had a very comfortable life in Russia. And I don’t want to immigrate and lose another ten years of my life to assimilate in some other country.

“I believe in the history of my country,” she added. “The times are very dark and very difficult, and every person who has a civil position who wants to make that civil position known must speak up. It’s very important.”

Below, more on Russia and Ukraine:

- A questionable partnership: Sources at Reuters told Politico’s Max Tani that staffers there are “frustrated and embarrassed” by the company’s ongoing partnership with TASS, a Russian state-owned wire service; the relationship largely went unnoticed externally when it was announced in 2020, but Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has meant that “more scrutiny is being placed on the arrangement, including from Reuters’ employees.” Reuters “downplayed its ties” to TASS, Tani reports, noting that while a business-to-business service offered by Reuters still provides TASS content to subscribers, the arrangement is independent of the Reuters newsroom.

- Press freedom in Ukraine: Oleh Baturyn, a journalist based near the Russian-occupied Ukrainian city of Kherson, has reportedly resurfaced after going missing and spending eight days in captivity. In a Facebook message posted via his sister’s account and reported by the Committee to Protect Journalists, Baturyn “did not identify his captors but said that in nearly eight days of captivity he was humiliated and threatened with execution.” The positive news of Baturyn’s release came as concern intensified as to the well-being of Viktoria Roshchina, a Ukrainian journalist who has been missing since last week. On Friday, her employer said that it believes she is in Russian military captivity.

- A new approach: Politico’s Ruby Cramer has a profile of Terrell Jermaine Starr, a US journalist based in Ukraine who is “redefining what it means to be a journalist who is as much a participant as an observer.” Starr “reports by way of highly personal and opinionated accounts on Twitter, in frequent cable news hits and in his podcast, Black Diplomats—first-person dispatches that bleed into humanitarian work, first in Kyiv, now in Lviv,” Cramer writes. “After a Russian missile attack struck nearby, he appeared live on MSNBC to talk through the ‘psychological trauma of what it means to be a refugee.’ He has helped transport three families to the border, tweeting along the way.”

- Meanwhile, in Germany: RTL, a German broadcaster, hired Karolina Ashion, a Ukrainian journalist, to host a ten-minute daily Ukrainian-language news show aimed at Ukrainians who have resettled in Germany since the invasion. “Ashion only made it to Germany about a week ago herself, following an arduous journey from Kyiv via Moldova and Romania,” the AP’s Philipp Reissfelder writes. “Her male colleagues, who aren’t allowed to leave Ukraine if they are between 18 and 60, are still broadcasting out of a bomb shelter in the country’s capital, she said.”

Other notable stories:

- For CJR, Andrew McCormick spoke with eight journalists who covered the US war in Afghanistan for an oral history rooted in their experiences. “Together, their input forms a history of sorts about the war’s coverage in Western media. In it, there are lessons for journalists—about whose stories we choose to tell, how the outlets we work for deploy resources, and how our perspectives come to shape the events we cover,” McCormick writes. “But the main point is simpler than that. It is only to ask and understand: What was it like to report on America’s longest war?” Also for CJR, Lynne O’Donnell explores what happened to Afghanistan’s journalists after the Taliban seized power. Just last week, officials detained three staffers at TOLO News. They have since been released.

- On Friday, media Twitter exploded after the Times published an editorial, headlined “America Has a Free Speech Problem,” claiming that Americans are losing “the right to speak their minds and voice their opinions in public without fear of being shamed or shunned.” Per Puck’s Dylan Byers, the editorial was “effectively commissioned by the paper’s publisher A.G. Sulzberger, and had been in the works for several months.” The Philadelphia Inquirer’s Will Bunch was among those to push back, arguing, in a column headlined “America has a New York Times–doesn’t-get-the–First Amendment problem,” that the US free-speech climate has “mostly been better than any time in our history.”

- The Post’s Jacqueline Alemany and Josh Dawsey report that the House committee investigating January 6 is looking to hire “high-profile journalists” to help write its report, part of a bid “to build a narrative thriller that compels audiences and is a departure from government reports of yore.” (If the 9/11 Commission’s report was lauded for its “narrative power,” Robert Mueller’s was not.) The committee is also aiming to put together a multimedia presentation, containing videos and other evidence, that will live online, as well as “blockbuster televised hearings that the public actually tunes into.”

- On Friday, during an NCAA women’s basketball game, Courtney Lyle and Carolyn Peck, the match announcers on ESPN, observed a moment of silence in solidarity with colleagues at Disney (which owns ESPN) who walked off the job in protest of a Florida bill that aims to ban schools from teaching young children about sexual orientation and gender. Announcers Stephanie White and Pam Ward held their own moment of silence during a game on Saturday, before Lyle and Peck did so again yesterday.

- For CJR, Timothy Karr, of Free Press Action, argues that the future of local-news innovation is noncommercial. “Local dailies were shedding jobs long before a few tech platforms reported ad revenues in the tens of billions of dollars,” Karr writes. “It’s a trend that points to a deeper problem with the business of local news—and to the need for solutions that don’t merely make Big Tech subsidize old ways of producing journalism.”

- On Thursday, the Corsican edition of France 3, a French public-TV station, broadcast footage that it had obtained showing a jailhouse attack that left Yvan Colonna, a Corsican nationalist who assassinated a French regional official in the nineties, in a coma. Hours later, bosses ordered the station to remove any reference to its story from its website. The reason is unclear, but the attack had already raised tensions in Corsica.

- Amid deteriorating diplomatic relations with France, the ruling military junta in Mali suspended the French TV channel France 24 and radio station RFI from the country’s airwaves, ostensibly over their coverage of abuse allegations against Malian soldiers. The junta also blocked the two outlets’ websites and banned local media from picking up their journalism. Emmanuel Macron, France’s president, condemned the decision.

- A court in Ethiopia extended the detention of Amir Aman Kiyaro, a freelance journalist for the AP who was arrested in November under a wartime national state of emergency that was lifted last month. Kiyaro has not yet been charged with any crime; the court’s ruling gave police eleven more days to interview witnesses in his case, after which point he must be either charged or freed. The AP’s Andrew Meldrum has more.

- And Sierra Jenkins, a twenty-five-year-old reporter at the Virginian-Pilot and Daily Press, was one of two people killed in a shooting outside a restaurant in Norfolk early on Saturday. (Three other people were injured.) “Sierra was on the way to becoming a rock star,” Brian Root, her editor, said. “It’s all about willingness and work ethic, and good god, she had that. And it hurts to talk about her in the past tense.”

ICYMI: As Britain looks to strengthen its libel laws, the US weighs weakening its own

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.