Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

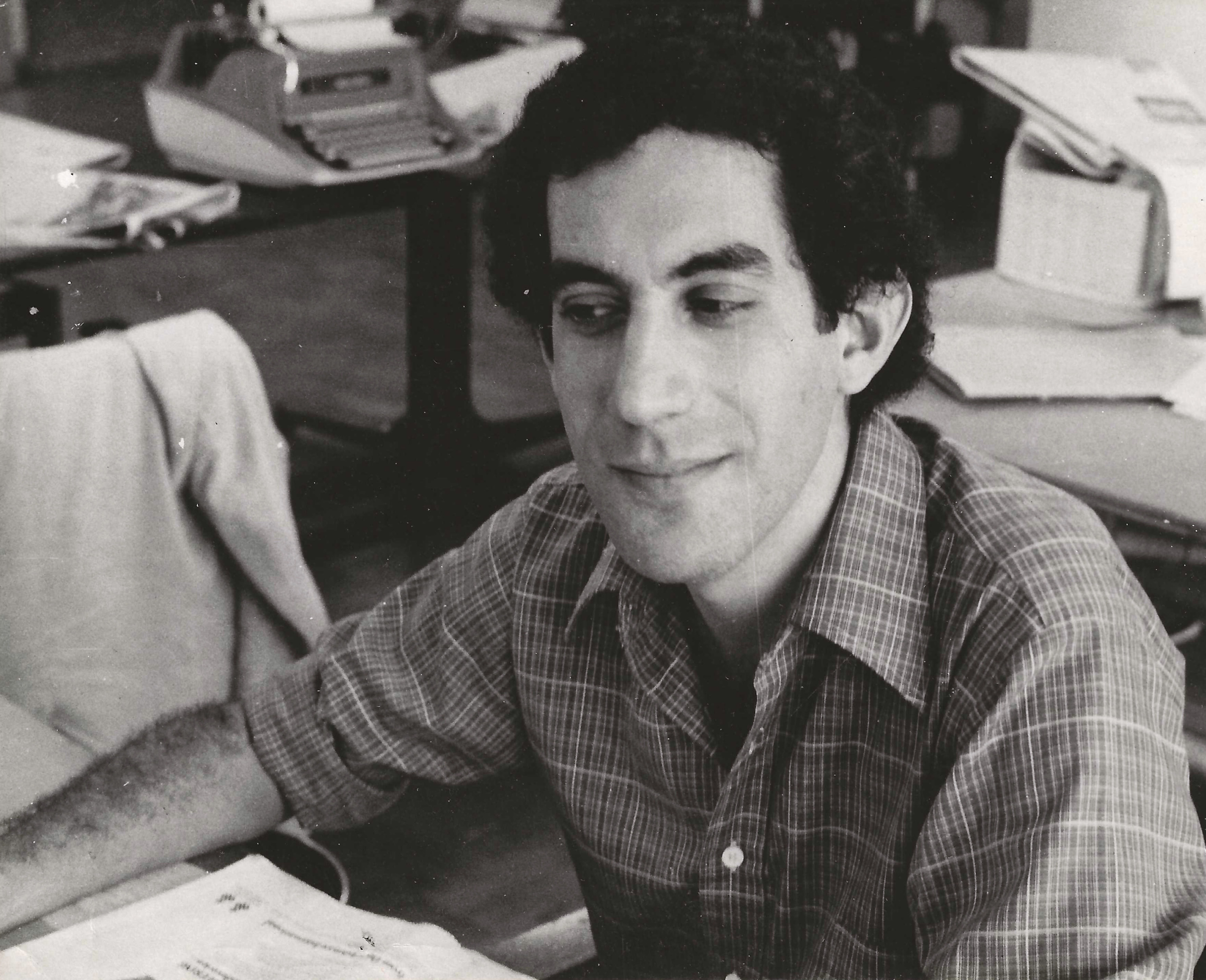

In 1979, at the age of twenty-eight, Stephen G. Bloom set out to Rio de Janeiro to work as a foreign correspondent for the Latin America Daily Post, one of several English-language newspapers in Brazil. The country was a destination for many expat reporters looking to jump-start writing careers. It was a moment when US interest in Brazil was high: in 1964, there was a coup, supported by the American government; countries around the world took an interest in Brazil for its agricultural production. For journalists, it offered a chance to be in the front row for global affairs—even as the papers where they worked were also, as Bloom describes, places for “deadbeats, ne’er-do-wells, grifters, drug runners, CIA agents, and pornographers.” All this, he says, created an environment like no other, where stories abounded and the opportunity to make the front page was endless.

Now Bloom, who these days is a journalism professor at the University of Iowa, has written about his experiences in his latest book, The Brazil Chronicles. A memoir woven with history, the book offers an entry into a bygone time for journalism, when newspapers still held immense influence over audiences, but didn’t always use that power for good. Bloom traces the long line of American journalists before him—Hunter S. Thompson not least among them—who worked at expat papers like the Brazil Herald, with which the Daily Post eventually merged, in search of career breaks.

Recently, I talked with Bloom about why young journalists needed to leave the US for their big break, the history of expat papers (and their nefarious side), and how today’s news environment differs greatly from the one in which he worked in Brazil. Our interview has been edited for length and clarity.

FM: Why did you decide to go to Brazil to work as a reporter?

SB: I always wanted to be a newspaper person, and I always enjoyed telling stories. I had my own favorite columnists, mostly from New York, because I grew up in New Jersey: Jimmy Breslin and Pete Hamill; a bunch of interesting writers. It sounds ridiculous, but I wasn’t willing to go to a small newspaper: I wanted to cover the big stories of my generation, but I couldn’t get a job in the US. I read about this newspaper starting up in Brazil. They said, If you can get yourself to Brazil, we’ll hire you. In rapid order, I got a visa, took a crash course in Portuguese at Berkeley—which was five hours a day, five days a week, for ten weeks—and bought a one-way plane ticket. I’ve always thought that the ultimate challenge in times of distress is the creative act. And here was a newspaper—a real newspaper—that was starting up in Brazil, and they were offering me a job. I went down there, and I had two of the most incredible years of my life. I also found that I was [part of] the latest generation of a whole series of American and British journalists like me.

Your book is a detailed look at this whole world of expat English-language papers. Can you describe how this came to be in Brazil, and what community it was serving?

Brazil has always been a place where “first world” countries are trying to extract wealth from the land. This is textbook colonialism. That money originally comes from Europe, but increasingly it comes from the United States. Brazil is an industrializing country. So that means they have to have roads; it has to have airports; it ultimately has to get electrified. And so you have all of these European or American companies sending down people who are minding the money that is being spent in Brazil. English speakers often don’t learn Portuguese, and they want to read about the news. There always have been expatriate papers serving that expatriate community. Starting back in 1825, there were English-language newspapers in Brazil.

One of the founders of the Brazil Herald was sent to Brazil by Ford Motors because the country was industrializing, and Ford wanted to position itself early for when [the creation of] roads led to cars and consumers. These newspapers became popular because they catered to their audience’s interests—reflecting the expats’ political and economic priorities, often skewing to the right, as the audience included bankers and businesspeople. They were the gatekeepers of Brazil’s exploitation, and tied to the patterns of colonialism and international investment.

What are the benefits—and downsides—of papers abroad that have been training grounds for Western journalists?

It was just a tremendously stimulating environment for a young journalist: [there are] lots of stories everywhere you look, and that’s what you want. They provided young reporters with an opportunity to get on the front page and learn how to work in a challenging, international environment. For a young journalist, it was a fast track to a career. Many journalists who worked for these papers, like me, were able to cover real stories and cut through the noise of smaller, less significant beats back in the States.

The downside was that these papers often acted as the gatekeepers of Brazil’s exploitation. The primary audience has always been people whose primary language is English, and so you’re writing for these stewards of Western money that’s being invested in Brazil. That was really very much shown in 1964, before I got there, in coverage of the Brazilian coup, which was totally endorsed and underwritten financially by the Americans. The Brazil Herald absolutely supported the coup. It was a strange kind of situation for those who believe in democracy, because this was a democratically elected government that was overthrown with the help of the Americans. And the newspaper, in many ways, reflected those Americans in Brazil. These papers weren’t necessarily writing for the local Brazilian audience or offering a critical view of the situation. Instead, they reinforced the colonial and exploitative narratives of the time. That’s a side of it that has always stuck with me.

Do you still see similar English-language newspapers abroad these days?

We have to get into the [US] election just for a bit: What’s the relevance of coverage of the owners and editorial policy of the LA Times and the Washington Post? Newspapers are getting more and more tame. That kind of stuff is beginning to happen in a major way with the Trump administration. I think journalists will be censoring themselves: We can’t do that story. In many ways, coverage of America from abroad might be better than it is in America itself.

I think there’s a lot of opportunity worldwide. There are wars going on that need to be covered. I’m not sure if we’re getting the best coverage of Gaza and Israel from US newspapers; I’m not sure if we’re getting the best coverage of the war promulgated by the Russians in American newspapers. I think that with the Internet, there’s tremendous opportunity to break out of the shackles that the American media has created because of the economic model.

You have said that The Brazil Chronicles is a celebration of what newspapers were and will never be again. What do you mean by that?

There’s a new study put out by the Pew Research Center finding that many Americans are getting their news from influencers. People gravitate to people who talk like them. There’s an echo chamber. I was on a commercial TV show recently, and someone asked me, Well, you’re a professor of journalism. What do you think about the future of journalism? And I said, dead. There’s no consensus on what journalists are supposed to be doing. The internet has changed that in many ways—in a negative way, but also there are opportunities now, because what we’re doing is we’re gravitating to our own echo chamber. I don’t know if it’s journalism, but there are opportunities now for different niche audiences.

There’s a lot of fun in being a journalist—it’s the best job in the world for a curious person. It gives you a front-row seat to history, the chance to ask questions that others only wonder about, and the ability to tell stories and have your name on them. That world of journalism, the one I experienced in Brazil, I don’t know if that’s going to continue for other people.

Other notable stories:

- CJR’s Meghnad Bose spoke with an anonymous female journalist in Afghanistan who has “continued to shine a spotlight on the plight of women living under Taliban rule” while taking extraordinary precautions to keep her and her sources safe (and who just won an award for her work from the Foreign Press Association in London). In related news, the United Nations published a report on media freedom in Afghanistan, finding that the Taliban regime has arbitrarily detained journalists more than two hundred and fifty times since coming to power in 2021. And ABC’s Trisha Mukherjee spoke recently with Afghan journalists who fled to neighboring Pakistan to escape the Taliban and applied for humanitarian visas from countries that pledged to help Afghan refugees—but are now living in limbo, unable to work in Pakistan and facing the threat of deportation.

- Senior leaders of Kamala Harris’s failed presidential campaign have spoken on the record for the first time about what went wrong, appearing for a roundtable discussion on Pod Save America, a liberal podcast hosted by former staffers in the Obama administration. Among other things, the senior Harris aides complained about aspects of the way the media talked about their candidate. Jen O’Malley Dillon, who chaired the campaign, said that Harris was hindered by a “bullshit” narrative that she was afraid to do interviews, that Donald Trump wasn’t held to the same standard, and that when Harris did do mainstream interviews, the questions were often “small and processy.” (CNN’s Brian Stelter compiled the media-related portions of the conversation on X.)

- The CEO of publishing company Hearst told Sara Fischer, of Axios, that it expects to earn nearly thirteen billion dollars in topline revenue this year—and that, for the first time in its history, more than half its profits will come from selling business services rather than its news media products. The CEO spoke after Hearst’s magazine division announced layoffs last week. At the time, their extent wasn’t clear, but New York’s Charlotte Klein now reports that nearly two hundred people lost their jobs and that the process was “particularly cruel”: a technical glitch meant that some affected staffers found out not by email but when they were locked out of a company messaging platform.

- In yesterday’s newsletter, we noted that The Onion’s acquisition of the conspiracy empire InfoWars in a court-mandated auction has been delayed while a judge considers whether the process was fair. (The satirical site plans to turn InfoWars into a parody of itself.) 404 Media’s Jason Koebler now notes that Elon Musk’s X has objected to the court-ordered sale of InfoWars’s accounts on that platform, claiming that X owns them; its legal basis for doing so is less interesting than the fact that X decided to get involved at all, Koebler writes, and should remind us all that we don’t own our online profiles.

- And we also wrote in yesterday’s newsletter about the recent presidential election in Romania, where a fringe far-right candidate qualified for a runoff seemingly on the strength of his presence on TikTok and other social platforms, after he was shut out by the mainstream media. Now Romania’s media regulator has asked the European Union to investigate TikTok’s role in the election, while a prominent centrist lawmaker in the European Parliament is demanding that the app’s CEO come in and testify.

Finally, a programming note: we’ll be off tomorrow and Friday for Thanksgiving. As ever, we’re immensely thankful for your continued readership in these turbulent and noisy times. Have a restful holiday, and we’ll see you on Monday.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.