Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Last weekend, Salena Zito became the first journalist to interview Donald Trump after a gunman tried to assassinate him at a rally in Pennsylvania, a conversation published in the Washington Examiner under the headline: “Trump rewrites Republican convention speech to focus on unity not Biden.” Trump told Zito that he had been preparing a “humdinger” of a speech, but that he’d ripped it up. “It is a chance to bring the country together,” he said. “I was given that chance.” As the Republican National Convention proceeded in Milwaukee, Trump’s team continued to push the unity theme and members of the media echoed it, with varying degrees of skepticism. In a piece quoting allies as saying that Trump had become “serene” and “emotional” in the wake of the shooting, Politico noted that, while he had since posted some unstatesmanlike things online, he had also “leaned into the notion of faith and divine providence, lending credence to allies’ private claims that he is engaging in deep reflection.” Last night, before Trump took the stage for his speech, Scott Jennings, a right-wing pundit on CNN, said that he’d already seen a chunk of it. “Buckle up,” Jennings advised, “because he’s about to blow the doors off and rise to the occasion.”

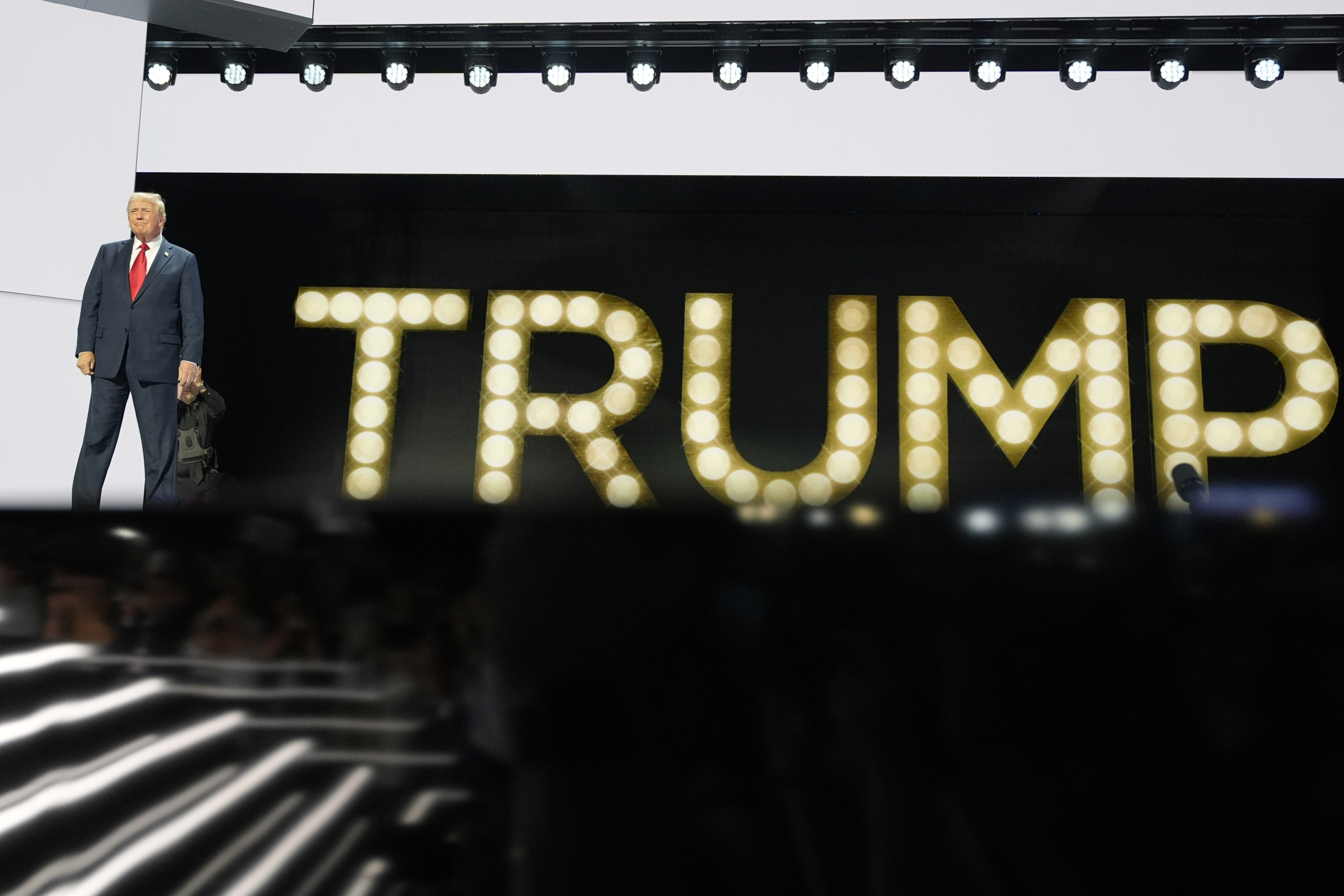

Finally, Trump appeared, framed by a giant sign spelling his name out in lights. (When the New York Post splashed the headline “Everything’s coming up TRUMP” on Tuesday, it surely didn’t imagine that the reference to Gypsy would soon be quite so visual.) As he spoke, he only mentioned Biden’s name once. (Well, technically twice, but the second time was to underline that he would only be saying it once.) “Typically Fiery Trump Calls for Unity at Republican Convention,” one headline read in the aftermath; “Trump urges unity at final night of the RNC,” read another. A news analysis in the New York Times noted that Trump had “attempted a politically cunning transformation.” Sure, he had proved unable to resist “a handful of exaggerations and personal attacks on Democrats”—claiming that Democrats cheated in 2020; calling Nancy Pelosi “crazy”; repeatedly referring to an “invasion” of immigrants and comparing them to “Hannibal Lecter.” But “open threats and nakedly vicious imagery were largely absent from his address,” as he exhibited both a “newfound temperance” resulting from his near-death experience and a “new approach” that “poses fresh challenges for Democrats.”

Even that article, though, seemed to be arguing with itself. (Headline: “Trump Struggles to Turn the Page on ‘American Carnage’”; subheading: “Trump promised to bridge political divides, and then returned to delighting in deepening them.”) And other major outlets seemed unconvinced by the whole unity thing. The Washington Post reported that Trump “wrapped a fresh gesture toward unity around his usual dark view of American decline and loathing for political opponents and immigrants”; other headlines read “Trump Calls for Unity but Shifts to Familiar Attacks,” and “Donald Trump called for unity at the top of his speech. Then he went after Democrats.” When Trump finally stopped talking—after an hour and thirty-two minutes—CNN’s Jake Tapper said that he had “started off with what we were told was the new tone of unity,” but then, “and I hope this doesn’t sound harsh, it pretty much became the kind of speech we generally hear from Donald Trump at rallies.” Chris Wallace added that he’d thought “we’re off to the races here, this is really gonna be a different Donald Trump,” only to come away disappointed. In between, they paused to take in what Trump claimed was “the biggest balloon drop in the history of balloons.”

As the New Republic’s Greg Sargent wrote earlier in the week, following the first credulous coverage of Trump’s unity rhetoric, media predictions of a Trump pivot are “a stock joke at this point.” It should be noted that not every journalist fell for this one, but it’s shocking—or, to Sargent’s point, perhaps not—that any member of the media would do so after eight years of similarly empty promises. Maybe they did so out of amnesia or gullibility. Maybe they really wanted to believe that Trump would play the unifier this time, reflecting, as the historian Rick Perlstein put it to me ahead of the 2020 election, an “ideology of consensus” at the highest levels of the elite media; the idea “that Americans are united and fundamentally at peace with themselves.”

If the credulous coverage and inevitable letdown felt frustratingly repetitive, they were, perhaps, a metaphor for a bigger feeling that has loomed over coverage of this week in particular. When the assassination attempt happened, it felt, rightly, like the press was witness to a truly historic moment: one of national unmooring, after which everything would, somehow, be different. But history is complicated, and not every historic moment marks a decisive turning point. By Monday, the news cycle had moved on—by no means entirely, but to a surprising extent given the gravity of the weekend’s events. By Tuesday, Derek Thompson was arguing, in The Atlantic, that pundits should stop pretending to know the import of the shooting, given that it “might not have any lasting effect on the election or politics in general.” (He spoke with an expert in failed assassination attempts who noted that “would-be assassins are chaos agents more than agents that direct the course of history.”)

It can be disorienting when events that we have been taught to see as turning points turn out to be a lot messier. (Perhaps, to be very charitable, this was another reason why some media observers seemed to believe that this time, Trump might actually pivot.) Maybe this was a turning point and the press just can’t see it yet. Still, at least for now, today’s news cycle does not feel categorically different from that of a week ago. Indeed, the buildup to Trump’s address was overshadowed by coverage of Biden’s future in the race, which was the big story this time last week and has ramped back up after a post-shooting lull, complete with the occasional public call for Biden to quit the race, a flurry of leaked private calls, and, now, an exchange of dizzyingly contradictory reports about Biden’s willingness to entertain the idea. (Gabe Schneider deftly satirized a typical push alert: “President Biden is appearing to accept the idea that he should discuss the concept of negotiating how he might listen to advisors who want him to review polling that says he should absorb the notion of him dropping out of the race.”)

This, of course, is not to say that the news cycle hasn’t changed at all, beyond the assassination attempt being a big story in itself. There has been an attendant debate as to whether it would lead major outlets to soften their scrutiny of Trump’s rhetoric and positions, often linked to the nebulous notion of turning down the temperature. As I wrote on Tuesday, there were some early signs that this might be the case. (This wasn’t just my observation: the same day, Trump’s son Eric remarked that he’d just done interviews with CNN and MSNBC and that he’d “never been treated with such respect.… I felt a different temperature.”) But as we have seen, other possible signs—not least the unity narrative—could just as well have reflected older forms of complacency. And some hard-hitting coverage has continued. The media is a big place; this week, in particular, generalizing about it seems perilous (even if any complacent coverage is too much).

Overall, the shooting and the ongoing Biden drama did seem to overshadow what seemed to be shaping up to be a dominant story out of the RNC: Trump’s hardline agenda for a second term, which, in the days prior to the shooting, had crystallized in growing media coverage (not to mention social media and celebrity chatter) about “Project 2025,” a detailed hard-right blueprint for a second Trump term that has been compiled by close Trump allies, even if Trump himself has publicly distanced himself from their plans. (The last pre-shooting episode of The Run-Up, the Times’ election podcast, was titled “Project 2025, Suddenly Everywhere, Explained.”) Again, it’s hard to generalize here. As the RNC has progressed, Project 2025 has popped back up in some coverage (including, yesterday, a buzzy Wired story linking J.D. Vance, Trump’s running mate, to figures involved with the project via an analysis of his public Venmo account). To the extent it’s been diluted by talk of Trump’s tone, this may have happened even without the shooting.

Either way, with the RNC over, the press will need to find new ways to examine Trump’s hardline agenda heading into the election, even if treating Project 2025 as a proxy for that agenda is a complicated proposition. On The Run-Up, Jonathan Swan advised taking it “seriously, as we have in our reporting,” but not as “Trump campaign plans.” But Swan also argued that the latter are hardly some mystery. “Donald Trump has said all of this out loud,” Swan told the host, Astead Herndon. “Literally he tells you,” Herndon replied. Swan advised listeners to “read his frickin’ campaign website” or “listen to a couple of tapes. It’s not Woodward and Bernstein here.”

The conversation put me in mind of an old cliché from the 2016 election—one coined by Zito, who also interviewed Trump back then and famously concluded that, while his fans take him “seriously, but not literally,” the press “takes him literally, but not seriously.” Coverage of Trump has evolved since then, of course, but as I see it, the literally/seriously balance remains something of a puzzle. His speech last night is a case in point. We now have a Trump record to assess—one that indicates that, when he talks about supposed Democratic election cheating and “invasions” of immigrants, he is being very serious, even if talk of Hannibal Lecter might not be literal. His promises of unity, on the other hand, were literal but didn’t deserve to be taken seriously at all; at least, not in the absence of evidence. Earlier in the week, Sargent suggested that “if media figures are so eager to depict Trump as unifying, then let’s lay down a hard metric”—that, before indulging such claims, Trump must clear “the absolute minimum threshold” of renouncing his election denialism and “authoritarian designs” for a second term. This is a welcome idea. In the absence of his doing so, the designs must remain the biggest story.

Of course, the press will also have to find ways to examine the Democrats’ agenda for a second term—a task complicated, for now, by the uncertainty as to whose agenda it will be. Yesterday, before Trump addressed the RNC, Vice President Kamala Harris spoke at a rally in North Carolina amid the swirling Biden speculation, and every major cable network covered it live. Viewers will have heard her talking about Project 2025—and about Trump’s claims of unity. “In recent days, they’ve been trying to portray themselves as the party of unity,” Harris said, of the GOP. “If you claim to stand for unity, you need to do more than just use the word.”

Other notable stories:

- In other news out of the RNC, Semafor’s Ben Smith wrote that he expected the big media story of the week to be GOP anger toward the press, but that reporters instead found “the friendliest media environment we’ve seen in years”—a result, Smith suggests, of MAGA’s current self-confidence. The Philadelphia Inquirer’s Will Bunch struck a different note in his own dispatch from Milwaukee. “The political pundits finally saw the thing they’ve been pleading for—unity—and what that really looks like,” he wrote. “It looks a lot like Jonestown.” Meanwhile, Tucker Carlson also took to the stage last night; the Times reports that he “delivered an unscripted monologue straight out of his old Fox News show, complete with off-color jokes and dark visions” of the future. And the Times advised its reporters not to call Vance a “son of Appalachia”—because he isn’t one.

- Lucy Schiller—who last year reported for CJR from a Pittsburgh-area care home, where she gauged older Americans’ impressions of the media—wrote for us again about Biden and “the semiotics of old age.” Writing about older people is a “minefield,” Schiller observes, “because ‘oldness,’ when viewed as a fixed category, immediately begins to dissolve; age looks different from person to person. A popular working definition of aging has something to do with separateness, in the form of retirement, potential debility, perceived out-of-touchness. Beyond that, we are left to look rabidly for signs; we know it when we see it, and yet are hard-pressed (like Justice Potter Stewart) to name the specifics. Perhaps the difficulty arises from our tendency to set such matters aside.”

- This morning, people around the world awoke to a huge outage involving machines using the Microsoft Windows operating system, the apparent result of a software update issued by CrowdStrike, a cybersecurity firm. (“This is not a security incident or cyberattack,” CrowdStrike’s CEO said. “The issue has been identified, isolated and a fix has been deployed.”) Amid the chaos—which also involved grounded flights and medical services going offline—the outage affected media companies. In the UK, Sky News went off air before returning with a stripped-back presentation; a BBC children’s channel also went off air, while various outlets in Australia “reported issues,” per Deadline.

- Media outlets have also experienced outages in Bangladesh—the result of mass protests in the country, sparked nominally by anger about government hiring practices, in which dozens of people are reported to have been killed, including a journalist who was covering the unrest for the Dhaka Times, a news site. Yesterday, protesters set fire to the offices of the country’s state broadcaster, as well as adjacent vehicles. (The broadcaster’s staff was safely evacuated.) Today, the government blocked mobile internet access and social media and shut down news broadcasts.

- And Lou Dobbs has died, at the age of seventy-eight. As the media reporter Brian Stelter notes, Dobbs played “a key role when CNN was founded in 1980” and was “one of the country’s foremost financial broadcasters,” but “later became better known for his anti-immigration and pro-Trump opinions.” After leaving CNN, Dobbs hosted a show on Fox Business that was canceled in 2021, after he broadcast conspiracy theories about the 2020 election. The voting-tech company Smartmatic later sued him for defamation.

ICYMI: Joe Biden and the semiotics of old age

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.