Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

There are things about the recent implosion of The Markup that make it unique—in particular, that it raised $23 million with nothing but a trio of co-founders and a brief description of the product they wanted to create. A launch like that places enormous pressure on a project. After not very long, Julia Angwin, one of the founders, was without a job, and The Markup was without five of its seven editorial staff members (who quit in solidarity). The source of those tensions, however, is not unusual in the startup world.

Reading through the description of events given by Angwin and Sue Gardner, her erstwhile co-founder and CEO, there is a consistent theme: the yawning cultural chasm between the business side and the editorial side of The Markup.

ICYMI: The story BuzzFeed, The New York Times and more didn’t want to publish

The “bean counters,” as journalists often call the business side of their offices, tend to fixate on metrics like page views and uniques, name recognition and Twitter followings. If you haven’t filed enough copy, generating sufficient page views, then your worth is suspect. The fact that you’ve spent months on an investigative scoop may be irrelevant if it doesn’t advance the bottom line. Journalists resist attempts to quantify that which is unquantifiable—like the impact of a story, or the sensibility of a hire.

On one side of the business/editorial chasm at The Markup was Angwin, an award-winning investigative journalist with a record of success at both The Wall Street Journal and ProPublica and a legion of supporters in media. She came up with the idea behind The Markup, then wooed Gardner to help turn it into a functioning business. She was the founder with the creative vision.

On the other side was Gardner, who ran the digital operations of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, then spent seven years in charge of Wikimedia, parent company of Wikipedia. Gardner’s task was by no means easy: to take Angwin’s vision and turn it into a credible journalistic organization—one that would be worth at least $23 million out of the gate.

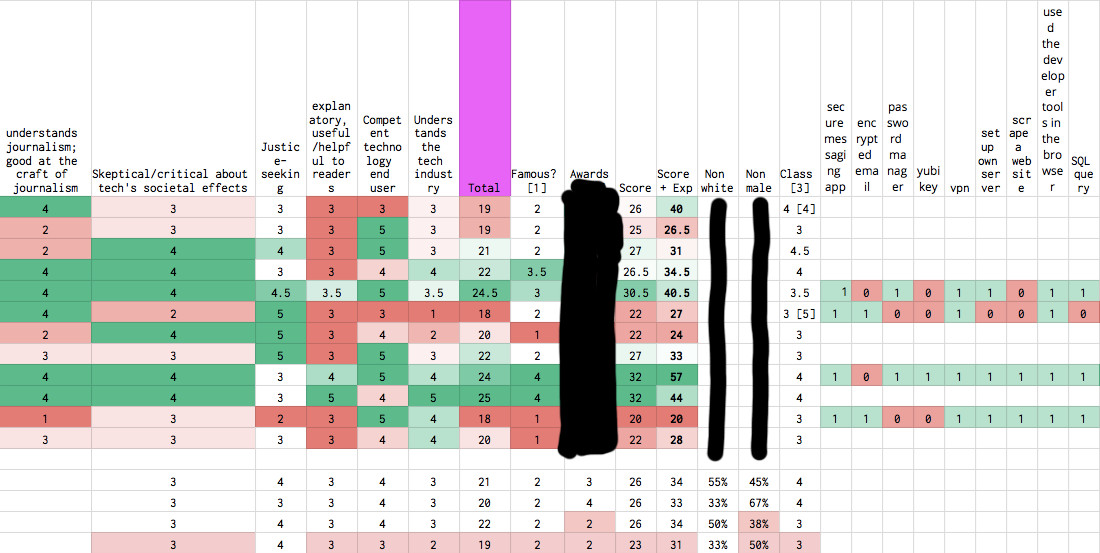

As I wrote a few days ago, Gardner created a spreadsheet that ranked potential employees on various criteria—including everything from their views of tech companies to their social status, as she perceived it: she guessed at candidates’ class, tallied their awards, and quantified whether they were “justice seeking.”

The spreadsheet, included here, is emblematic of that gap. Angwin, in comments on Twitter, said that she didn’t know the spreadsheet ranked potential candidates by class until a week ago, and was “horrified” to learn of it. (Gardner sent it to CJR with the names redacted; we have removed additional identifying information. It is unclear whether any of the people referenced were actually hired).

A key below the spreadsheet explains some of Gardner’s thinking: “Obviously I am guessing here,” she writes of the column for social class. The criteria are: “1) very poor family background, 2) working class, 3) middle class, 4) slightly upper middle, and 5) super rich, super privileged.” (Another note suggests that “Wesleyan University, semester abroad, Columbia graduate school” and “went to state college” are also criteria for “class.”)

A key for the column marked “Famous” describes the criteria as: “1) has only published in small media, or hasn’t published very much 2) has published regularly in ordinary-sized media 3) has published a LOT in ordinary-sized or larger media, or has a social media presence exceeding 10K, 4) has published a lot in very popular media AND has a social media presence bigger than 10K 5) practically a household name.”

From the beginning, Gardner says she found the relationship with Angwin unnecessarily adversarial. When Gardner proposed that Angwin take the Myers-Briggs personality test or a similar quiz called the PMAI test, she bristled. For Gardner, the Myers-Briggs—and the books and blog posts on management that she shared with Angwin—were helpful tools for getting to know the people with whom she was creating a new company.

Angwin says she believed—based in part on the spreadsheet—that Gardner and fellow co-founder Jeff Larson wanted to change The Markup into an anti-tech advocacy group instead of a fact-based reporting project. (Larson and Gardner both deny that they planned or wanted such a shift.)

After Angwin was fired, dozens if not hundreds of journalists howled with outrage at the idea that she would have to take a Myers-Briggs test. Tom Gara from BuzzFeed said on Twitter that “the most important test of any investigative journalist is how vigorously they tell you to fuck off if you try to make them take a Myers-Briggs test;” others derided it as a “load of unscientific horseshit.”

A successful startup depends on two halves of a single brain: one half that does the creative stuff, the other half that handles the business necessities. At The Markup, both sides were at war.

ICYMI: Teacher facing possible firing over student sex worker profile

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.