Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Proposals to change the Social Security system are fast taking shape, and many of them call for substantial benefit cuts for young workers. While a handful of journalists have discussed these “tweaks,” as the president calls them, there has been little discussion about how such changes will fit into the total picture of retirement income for most Americans. And there’s been little talk about the huge gulf between what the public wants and what Washington favors.

I sat down with Social Security expert Alicia Munnell, who heads the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. Munnell has a lot to say, but her words have largely been absent from this year’s reportage, which has been characterized by he said/she said commentary from a narrow range of voices. Munnell’s comments point not to a deficit crisis but, she argues, to a looming crisis in the adequacy of retirement income that must be considered in the context of any changes to the system. This is the second in a series of conversations with experts on Social Security and retirement income.

Trudy Lieberman: Should Social Security be part of the push for deficit reduction?

Alicia Munnell: Social Security can’t be a big part of deficit reduction because it doesn’t have a big deficit. Whereas a combination of cuts and taxes sounds so fair, in this case it’s not appropriate, because they would be part of the retirement income system that already is going to produce inadequate income for most Americans. To further cut back doesn’t make sense.

TL: Why are some people pushing an increase in the retirement age?

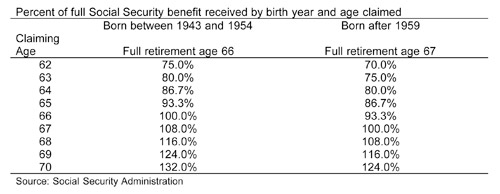

AM: This solution has always arisen when there’s talk of closing the financing gap. It’s a way to cut benefits that sounds like it’s not a benefit cut. But if people have to wait longer to receive their full benefits, they will get less over the rest of their lives. And people who take their benefits early will also receive lower monthly benefits. As you move the age further out, the benefits for those taking them early drop [see table] substantially. Doing this does help close the gap between benefits and existing revenue, and so it seems reasonable to many.

TL: Don’t people have to wait longer now to collect full benefits?

AM: Yes, many people don’t know that the age for receiving full benefits has gone from sixty-five to sixty-six, and will be increasing to sixty-seven for those born after 1959. Many people still think the age is sixty-five, and they are not factoring that into their thinking. Increases are already in play.

TL: Is it reasonable to expect people wait until age seventy, as some suggest, to collect full benefits?

AM: While people in general are healthier than they once were, for many of them working longer is an impossibility. They have health problems, or a spouse does. Their work skills may be antiquated, or they live in areas of high unemployment.

TL: How many people are in this category?

AM: About twenty-five percent of the population.

TL: But more people than that take their benefits early. Why?

AM: About half of all beneficiaries take their benefits at age sixty-two. It’s part of the culture. Social Security field offices try to be helpful, and in doing that they tell people they can take their benefits early. The fact there’s a deficit in the program also encourages some to take them early. They feel they should get them while the getting is good.

TL: But there are downsides, aren’t there?

AM: Yes. Those taking the benefit early may not have too much trouble financially while they are still in their sixties, but by the time they are in their seventies and eighties, they will have used up other assets. Too many people will depend solely on Social Security, and they will find their monthly benefit inadequate.

TL: Does that argue for staying in the workforce longer if you can?

AM: I am sympathetic to the notion that people who can work should work as long as they can. Under current law, a monthly benefit taken, say at age seventy, is seventy-five percent larger than it would be at age sixty-two.

TL: How much lower is it if you leave at age sixty-two?

AM: Right now it would be twenty-five percent less.

TL: Should raising the age be part of the solution to the system’s shortfall?

AM: I don’t think we need to increase the age very much. As noted earlier, Social Security’s full benefit retirement age is already scheduled to rise to sixty-seven. Raising it to age seventy is such an unnecessary and extreme position. It’s more than needs to be done. Instead, indexing it to reflect increases in life expectancy would probably make sense. It would encourage people to stay in the workforce longer. The way to insure a secure retirement is to get as big a monthly benefit from Social Security as possible. Work isn’t all bad. It gives people a sense of purpose and a structure to their day. But something needs to be in place to catch those who cannot work longer.

TL: What would that be?

AM: If we raise the early retirement age, we need to have a disability benefits system with relaxed criteria. It needs to be flexible. The core principle is to allow those who can no longer work sufficient income to avoid impoverishment.

TL: Then does the age for collecting early retirement benefits also have to increase?

AM: We would also have to raise the eligibility age for taking benefits early so people don’t end up with miniscule income. If the age were raised to seventy, the reduction at sixty-two would be substantial. Someone born after 1959 when the normal retirement age hits sixty-seven is already scheduled to lose thirty percent of their full benefit.

TL: How much of a reduction will someone taking benefits at age sixty-two face if the normal age is raised to seventy?

AM: Based on the current rate of reductions for those claiming early benefits, the reduction would likely be near fifty percent.

TL: Is anyone talking about raising the early retirement age?

AM: No. But the two have to be coupled together.

TL: Social Security has been credited with moving large numbers of seniors out of poverty. If the age for full benefits is raised and the one for early retirement is not, won’t that wipe out the gains in income Social Security has brought?

AM: It wouldn’t wipe out all the gains, but it would significantly reduce Social Security’s ability to help ensure adequate retirement income. And even today we still see pockets of poverty among widows. A couple may start with an early benefit which the husband takes at sixty-two and when the husband dies, the wife gets only fifty percent of her husband’s benefit (or her own if it’s larger, but it often isn’t). That makes the benefit even more inadequate. The husband’s pension, if he had one, usually disappears. When that happens, Social Security is all she has. If the normal retirement age goes much higher, a woman in this situation will see a big decline in her household benefit and won’t have enough to live on.

TL: That brings up the matter of how much money do families need to live on in retirement. What’s the target people should be aiming for?

AM: In general, people need about seventy percent or what they lived on before they retired.

TL: How much of pre-retirement income is Social Security intended to replace?

AM: Let’s consider people in the middle of the income distribution with a pre-retirement income of around $45,000. For someone retiring right now, it will replace about forty percent of that income.

TL: Isn’t the replacement rate going to go down, meaning that Social Security will replace less income?

AM: Yes, when the changes mandated by the 1983 amendments gradually increasing the retirement age to sixty-seven are fully in effect, beneficiaries can expect Social Security to replace less of their income. For workers in the middle of the income distribution, it will replace thirty-six percent.

TL: If the retirement age were increased to seventy, what would the replacement rate be for those workers?

AM: About thirty percent.

TL: Won’t people be at even greater risk of not having enough income?

AM: Yes. The National Retirement Risk Index published by the Center measures the percentage of working age households who, at retirement, are at risk for not maintaining their pre-retirement standard of living. Using a lot of conservative assumptions, we found that based on 2004 data, 43 percent of households were at risk. After the stock market crash and the economic collapse two years ago, 51 percent were. That’s an extraordinarily high number.

TL: Social Security was always considered one leg of the three-legged stool of retirement income. Can people count on help from the other two legs—private pensions and personal savings?

AM: Not really. Let’s first look at employer-sponsored pension plans. At any one moment in time, only half the people in the private work force has any pension plan like a defined benefit plan or a 401(k) plan. Pension coverage is much higher in the government sector where about 80 percent of workers have a plan. The percentage of workers with any type of employer-sponsored pension has not changed, but the nature of the plan has changed dramatically.

TL: How so?

AM: We’ve gone from defined benefit plans that pay a benefit for the life of the retired worker to 401(k) plans where people accumulate a sum of money and are responsible for providing their own retirement income.

TL: Is that a bad thing?

AM: Yes, that’s a bad thing. I’m not saying defined benefit plans were perfect. You had to stay in a job a long time to get the full benefit and that doesn’t happen anymore. But defined contribution plans have a serious drawback, in that they transfer all risk and responsibility to the individual workers, and people make mistakes every step along the way, from failing to participate in a plan, to investing unwisely, to trying to manage their own lump sum in retirement.

TL: Isn’t a 401 (k) plan a type of defined contribution arrangement?

AM: Yes. It is a unique kind of defined contribution plan that shifts risks and financial decisions from employers to employees. When they were first introduced, 401(k) plans were meant to supplement defined benefit plans. But now they’ve become the dominant kind of pension. They really were designed for another purpose.

TL: Why did defined benefit plans disappear?

AM: Before 2000, employers did not get rid of these plans, but they began to disappear because they were predominant in declining industries. After 2000, it was another story. It was the perfect storm—declining interest rates and a declining stock market and an increase in the plans’ liabilities that required employers to increase their contributions. Instead of doing that, they froze the plans, and that meant workers who had them could no longer accrue benefits. So 401(k) plans became the only type of plan for millions of workers.

TL: How much money on average do people have in 401(k) accounts?

AM: Before the crash it was about $70,000 for those nearing retirement.

TL: Is that a lot considering a family’s retirement needs?

AM: No. People who don’t have much money see it as a big pile, but as a stream of money to support you in retirement, it is not. When you convert that average amount into a joint-and-survivor annuity where the surviving spouse gets the full benefit when the other dies, it works out to about $338 a month for a sixty-five year-old man and a sixty-two year old wife who are annuitizing their 401(k) money today. If the man were to take a single life annuity, his widow would get nothing, but the monthly payment would be only $100 more, or $438. That, plus an average Social Security benefit of about $1100, wouldn’t give the family much to live on unless they had additional savings.

TL: What about savings outside a 401(k) plan? Do people have much?

AM: Most have virtually nothing—about $30,000 in financial assets on average for those Americans approaching retirement. Americans don’t save unless there are organized savings mechanisms. The only place they have money is in their house. A house is an extremely important financial asset for most middle-income families. We need to create more financial mechanisms that let people stay in their homes, like reverse mortgages, which let people live off the equity that has accumulated. Under a reverse mortgage, a homeowner borrows against his equity and receives money from a lender. Unlike a home equity loan, no loan payments or interest are due until the individual dies, moves out, or sells the house. When one of these events occurs, the borrower or his estate is responsible for repaying the loan in full.

TL: Are these very common?

AM: Only about two percent of people who can take them do. People who have finally paid down a mortgage are reluctant to take out another one. And the fees on these products tend to be high.

TL: How will continually rising health care costs affect families who may have too little retirement income?

AM: I hardly know what to think about medical costs that are projected to increase at enormously high rates each year. It’s not clear how people can protect themselves.

TL: It sounds like another perfect storm is brewing—lower Social Security replacement rates, no more defined benefit plans, and little cushion from 40l (k) plans. What should people do?

AM: People should delay taking their Social Security benefits early if they can. They can help close the expected shortfall by working a little longer—say three or four years until they get to normal retirement age for full benefits. That will make a big difference for many families. Each year you delay taking Social Security after your normal retirement age, your benefit increases by eight percent.

TL: What should be done from a public policy standpoint that could improve a family’s well being in retirement?

AM: We need a new tier of retirement savings. The goal would be to combine the best aspects of a defined benefit plan and a defined contribution plan. This new tier would produce another 20 percent of pre-retirement income for families. Participation in such a plan should be either mandatory or strongly encouraged (though defaults). The accounts would be funded by contributions from employees, and perhaps employers, with low-income workers receiving some form of government subsidy. Participants should have very limited access to money before retirement, and benefits should be paid as annuities. The new tier should reside as much as possible in the private sector.

TL: How would this be different from privatizing the system? Or would it be a foot in the door?

AM: It would not affect Social Security benefits, which is generally what people mean when they discuss privatizing the system. These accounts would represent a new source of savings to supplement both Social Security and employer-sponsored plans.

TL: What are the policy solutions to closing the Social Security shortfall that deficit hawks are so concerned about?

AM: We have to put in more money, either through a slight increase in the payroll tax or having the tax apply to more wages.

TL: What is the earnings cap right now?

AM: Social Security taxes apply to $106,800 of income, and that covers about 84 percent of all wages. We could raise the payroll tax rate from 6.2 percent that is paid equally by employers and employees to 7.2 percent. Or we could raise the cap so that the tax applies to 90 percent of all wages.

TL: Has the press adequately informed the public about all of the options?

AM: One can understand why it hasn’t been given top billing, given everything else going on. But there needs to be more financial literacy, and the press can help out here. Our center has produced some materials that explain what happens when you take Social Security early, the options for fixing the Social Security shortfall, and the nuts and bolts of claiming Social Security benefits. People can find out more about them at http://crr.bc.edu.

TL: Is it necessary to fix Social Security during a lame duck Congress in December, as many have suggested?

AM: I don’t want to see any change to Social Security this year. We haven’t really had a debate.

TL: How can we foster such a debate?

AM: Policymakers are reluctant to cut benefits or raise taxes due to fears of the public’s reaction. Therefore, one way to improve the climate for a debate is to first raise the level of public knowledge of both the nature of the problem and the implications of different options for addressing it.

Click here for more from Trudy Lieberman on Social Security and entitlement reform.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.