This report is part of an ongoing, multi-year study by the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia Journalism School into the relationship between large-scale technology companies and journalism.

This research is generously funded by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Open Society Foundations, John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Abrams Foundation, and Craig Newmark Philanthropies.

Executive Summary

The relationship between technology platforms and news publishers is entering a new moment. In interviews conducted since we published our last report, “Friend and Foe: The Platform Press at the Heart of Journalism,” in June 2018, publishers spoke of what they called the end of a platform “era.” This era, one defined by the belief that the massive audiences platforms offer would lead to meaningful advertising revenue for publishers, was a “bubble” and a “distraction,” they said. This promise has proven to be a broken bargain. Finally, publishers believe “the scale game is over.”

This acknowledgment, repeated throughout interviews conducted in early 2019, was a significant departure from years past. Throughout much of 2018, publishers were still optimistic that partnering with platforms on scale-based products and initiatives could help sustain the business of journalism—despite years of pushing their content to these platforms without consistent returns on their investment.

Publishers continue to rely on a variety of platform products, but the ethos of collaboration that infused our research in 2018 has since significantly diminished. More openly than ever before, publishers expressed heightened distrust toward platforms. And while in past interviews they appeared willing to overhaul parts of their businesses to fall in line with platform maneuvers, their priorities were more focused this time around: Post-scale success necessitates regaining control of revenue streams and putting core audience interests above platform demands.

Last year, we observed strong signals that publishers were looking to bring audiences back to their own properties over “social-first” publishing. In 2019, the trend gained momentum. Many publishers interviewed openly regretted focusing on brand-diluting social content during the scale era, at the expense of undervaluing their core audiences, and have subsequently recommitted to serving their most loyal readers. From a business perspective, this means diversifying reader revenue streams to include, for example, events and membership programs.

Our key findings from this phase of research are:

- The most discernible difference between past findings and those of our most recent interviews is that any hope that scale-based platform products might deliver meaningful or consistent revenue for publishers has disappeared. This does not mean, however, that publishers will no longer work with platforms—an impossible scenario, as the latter are the gatekeepers of the online information ecosystem—but rather that any optimism about the ability of ad-based products to sustain journalism seems all but gone.

- The 2018 Facebook algorithm change de-emphasizing news content on News Feed confirmed a previously theoretical fear: that platforms can turn off “audience taps” on a whim. The fallout from disappearing traffic forced publishers to train their focus on the core audiences that some admit they had previously taken for granted. Rather than chasing clicks and shares on social media, publishers recommitted to serving their most loyal readers (or trying to: The transition is proving treacherous for those most dependent on advertising dollars).

- In previous reports, publishers used the word “diversification” to reference diversifying platform strategies—in other words, putting resources toward a variety of platform products. In this round of interviews, however, publishers spoke of diversification almost exclusively in the context of squeezing revenue from their own properties in as many ways as possible. This often involves reader revenue (membership or subscriptions) and new products to drive that revenue (newsletters), events, branded retail products, sponsored content, affiliate links, agency services, and, of course, traditional advertisements.

- After years of contradictory public statements, platforms have lost credibility with many publishers. Our interviewees were more skeptical than ever of platforms’ commitment to helping journalism and often framed platforms’ journalism initiatives as mere PR moves.

- Unlike in the past when publishers were eager to participate in new platform products, they now have a heightened bar for signing on. Due to years of disappointing returns on investments, many publishers described no longer feeling a “fear of missing out” when it comes to platform opportunities. Instead of crafting strategy around platform products and hoping for revenue, publishers are planning around revenue, and from there determining which platform products might provide a means to that end.

- Publishers’ owned audiences increasingly determine editorial. Instead of commissioning stories around what performs best on platforms and measuring success by audience size, publishers are focused on serving their core audiences, regular readers likely to become a source of revenue. The platforms are a secondary consideration. That being said, those publishers most dependent on ad revenue are more likely to find themselves still prioritizing clicks, and therefore chasing what’s trending on platforms.

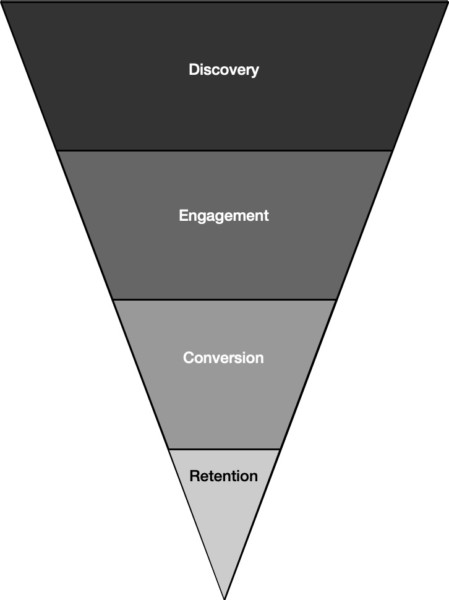

- As more news organizations turn to direct contributions from audiences, interviewees from various newsroom types repeatedly spoke of platform products not as money makers but as marketing vehicles to capture readers at the top of an engagement funnel, with an eye toward eventually converting them into paying readers.

- A conversion-focused strategy requires thinking about audience data and metrics in a new way, setting different goals and benchmarks, and seeking more granular insights. As publishers seek to regain control of their audiences, they are segmenting them with the aim of better focusing on serving their core readers, while strategizing around converting more casual readers. Some reader categories we heard included: “drive-by,” “grazers,” “most loyal fans,” and, of course, “subscribers.”

- Sensing the opportunity to insert themselves into this funnel process, platforms have been quick to unveil new subscription products that offer to take “friction” out of “conversion.” Google offers Subscribe with Google and Facebook rolled out a paywalled version of Instant Articles. Just as publishers previously had to weigh the pros and cons of ad-based platform publishing products, they are now facing similar decisions over which platform-led subscription products to use—and how.

- The increased public scrutiny of big platforms’ effects on society and democracy has led to new ethical considerations for publishers and their audiences. Some newsroom employees wonder whether their companies should accept platform money, and if leading their audiences to platform properties makes them complicit in a harmful information ecosystem.

While it is tempting to frame this new phase as empowering for publishers, the power dynamics at play still do not bode well for the future of the online media industry. With this in mind, what will a post-scale world look like for online news publishing?

One hint comes in the form of the latest platform product rollout, the Facebook News tab. A total departure from Facebook’s first major publisher product, Instant Articles—which required publisher content to live on the platform inside the News Feed and whose revenue potential was ad-based—News tab stories will be presented in a dedicated and differentiated news section, curated by human editors and aided by an algorithm. Publishers will choose whether users read entire stories there or are redirected from a preview to their own sites. Regardless of that choice, some publishers will be paid for their participation.

Payments vary from outlet to outlet, but so far they’ve been reported to reach as high as seven figures. Participating publishers range from the Chicago Tribune to The Atlantic to Fox News, and even includes The New York Times, which was quick to abandon Instant Articles in 2017 but described the News tab as a “truce.”

Meanwhile, Google and Facebook have kickstarted investments they say will total 300 million dollars apiece over the next three years into news initiatives, particularly those aimed at grants and trainings for local newsrooms. In Google’s case, the company has done what was practically unimaginable when our research began: directly fund the creation of new local newsrooms.

This strategic shift from news products toward news initiatives renders these platforms more patrons than partners of journalism. Thus, as platforms become the de facto policy makers of an information ecosystem not designed with journalism as top of mind, a line between platform and publisher that’s always been blurry is being erased.

Regardless of labels, what remains constant is the distribution of power. There are those who make the rules and those who adapt to them.

Introduction

Since our last report was published in June 2018, the shift in the journalism landscape has been seismic. Advertising revenues have continued to plummet and newsrooms across the country have experienced mass layoffs. In turn, publishers have scrambled to adapt their business models and priorities in an ever-changing and volatile media ecosystem—one still dominated by platforms despite the large-scale public reckoning with their effects on society and democracy.

For the majority of publishers in our study, Facebook has been integral to their publishing operations for years now, and had an outsized effect on their audience and revenue numbers. In the months after Facebook’s January 2018 algorithm change to deprioritize publisher posts on the News Feed in favor of updates from friends and family, publishers began to realize the extent of the drop in traffic. Slate reported, “For every five people that Facebook used to send to Slate about a year ago, it now sends less than one.”

Publishers’ anticipatory angst about how the change would affect readership and therefore revenue numbers proved to be well founded, even as their worries had been swiftly dismissed early last year by Facebook’s head of global news partnerships, Campbell Brown. She said, “If anyone feels this isn’t the right platform for them, they should not be on Facebook.”

But for those already deeply invested in the platform, it was devastating to watch as audience numbers for publisher posts on Facebook and referral traffic to publisher-owned websites crashed throughout the year, bringing advertising revenue down with them.

The lesson of platform unreliability, particularly when it comes to revenue, has never been more clear to publishers. Building on the pivot toward reader revenue that we highlighted in our last report, dozens of publishers have since put up paywalls or launched membership programs, including Vox, Quartz, TechCrunch, and New York Magazine. Even once-digital-darling BuzzFeed is re-strategizing as the platforms on which it built its business evolve in unexpected directions.

BuzzFeed is one of many newsrooms to suffer from sweeping layoffs, with more than 200 of its employees losing their jobs in the past year. Meanwhile, The Outline, Refinery29, Mic, and Vice have cut more than 400 jobs since September 2018, with Mic effectively shutting down. This is all in addition to cuts in legacy newsrooms like CNN and Meredith Corp., which have slashed more than 300 jobs in that time. Some of the most significant layoffs have taken place at national local chains like Gannett and McClatchy, which axed more than 850 jobs this year alone. A Bloomberg article estimates journalism jobs lost in 2019 to be around 3,000.

The precarity of digital media businesses in a platform-dominated internet has led to an industry-wide resurgence of labor organizing. In the last two years, newsrooms from The New Yorker, Vox, Slate, Fast Company, Refinery29, and even the podcast company Gimlet have unionized. But union campaigns have not been easy. Joe Ricketts, the billionaire owner of DNAinfo and Gothamist, shut down both local news organizations after their employees voted to unionize. At Vox Media, management did not agree to certain contract demands until more than 300 employees staged a walkout. A similar walkout by BuzzFeed News employees followed tense negotiations. The union has since been recognized. The latest effort to meet resistance is at Hearst Magazines, where staff at several of its publications are trying to unionize.

Given this environment, new platform product rollouts over the last year were met with an unprecedented level of caution. When Apple introduced Apple News+ (a personalized digital subscription newsstand of sorts) in March, it did so without the participation of The New York Times and The Washington Post, which the platform had reportedly tried and failed to recruit for inclusion. Though Apple did successfully get The Wall Street Journal aboard, many news organizations remained wary after getting burned by just about every other similar platform product promising meaningful revenue. Apple’s revenue sharing proposal, in which the company would keep 50 percent and all participating publishers would split what remained, was swiftly criticized. New York Times CEO Mark Thompson warned against the product days before it hit the market, drawing a comparison to Netflix.

“Even if Netflix offered you quite a lot of money . . . does it really make sense to help Netflix build a gigantic base of subscribers to the point where they could actually spend $9 billion a year making their own content and will pay me less and less for my library?” he asked. Already, Apple News+ is reportedly struggling to attract subscribers, and Apple may bundle the product with its others, like Music and TV+.

Since our last report, Google and Facebook have started to fund various news initiatives, particularly those aimed at local coverage. This is a 180-degree shift from how these platforms treated local news at the outset of our research in 2016, when new products like Instant Articles and Snapchat Discover were aimed at or reserved for national or household-name publications alone. In fact, in early 2019, the race to support local news resulted in a game of one-upmanship among platforms. In January, Facebook earmarked 300 million dollars to local news, and in March held its first local news summit to meet with publishers about the local news crisis and their wants from the platform. That same month, Google introduced a boot camp for eight local subscription publishers, similar to one Facebook hosted last year.

In May, Google announced that its Digital News Initiative, which has previously been focused only in Europe, would fund efforts in the United States. Unsurprisingly, the aim was “on projects which generate revenue and/or increase audience engagement for local news.” Then in September, Facebook announced the first recipients of its “Community Network” grants, which are meant to “support initiatives that connect communities with local newsrooms.” In sum, the money that Facebook, Google, and the Knight Foundation, which works closely with and receives funding from both platforms, have pledged toward local news is roughly one billion dollars, to be delivered over the next several years.

Another trend to surface over the last year is the pronounced shift in platforms’ eagerness to engage in editorial practices—whether by actually producing journalism or by selecting stories or publishers to feature. LinkedIn now has a full newsroom. Twitter started more carefully curating its Moments tab, with annotations accompanying collections of tweets that are written by a team of human editors. Apple worked with select partners for a special Midterm Elections section in Apple News. And in March 2019, Google announced that for the first time it would directly fund the creation of new local news websites launching in the US and the UK.

Facebook remained reluctant, until this spring, to treat news in some hands-on way, as distinct from all other content. That all changed in April when Mark Zuckerberg announced he was considering paying for “high-quality news” and separating it into its own news feed—plans that were confirmed in June. Intervening with human judgement about surfacing content is a practice from which Facebook had run fast and far after it disbanded the team that curated news for Trending in 2016. But it seems the platform has again decided that leaving its news ecosystem to algorithms is unsustainable. Facebook hired a team of journalists to curate its new News tab, aided by algorithms, and is offering some publishers millions of dollars to license their content.

The shift toward becoming more hands-on was necessitated, at least in part, by a seemingly endless string of PR crises. After long resisting direct action against the rise of white nationalism, hate speech, and harassment on its platform, this spring Facebook published a post on “standing against hate” and banned Alex Jones and Milo Yiannopoulos. In May, Twitter was pushed to start rerouting users in search of anti-vax information on its platform, instead showing them “reliable public health information.”

Facebook, in particular, has taken a series of steps that could reshape the company from its core in the coming months. In January, struggling to moderate problematic content with technology alone, the platform announced it would create an “oversight board for content decisions.” In March, Mark Zuckerberg wrote a post on building “a privacy-focused messaging and social networking platform” and then redesigned the platform the following month to be “more trustworthy.” In June, the company announced it would roll out “a new global currency powered by blockchain technology.” This digital currency, expected in 2020, will be called Libra. Its launch, however, remains uncertain as it hits up against potential US regulatory restrictions.

There is no telling how publishers will fare in the coming years as platforms undergo perhaps their most dramatic transformations since their foray into publishing products in 2015. However, one thing is certain: Despite facing increasing antitrust scrutiny and calls for regulation, platforms are more powerful than ever. Over time, they have come to control the online information ecosystem and, increasingly, in the case of Facebook and Google, are among the news industry’s top funders.

It is in this context that many of the publishing executives and employees we interviewed described the “end of an era.” But as is clear in the report, this does not mean the end of their cooperation with platforms. It refers, rather, to the end of optimism that scale and ad-based platform products will bring about meaningful revenue and audience growth. From the rise of paywalls and reader revenue initiatives to the diversification of revenue streams through live events and podcasts, publishers are attempting to regain control over the future of their businesses.

Methodology

We conducted 42 interviews with individuals from 27 news organizations (representing national and local legacy outlets, national and local digital natives, broadcast, audio, and magazine), six platform companies, and one foundation. These interviews were carried out primarily over the phone, lasting 30 to 90 minutes, and were recorded and transcribed. Interviewees were promised anonymity and confidentiality, and guaranteed that their responses would not be identifiable in the final results. The conversations were semi-structured and centered mostly around editorial, audience, and revenue-related platform strategies. Because the focus of this research was publisher reactions to the evolving platform ecosystem for news, the bulk of our interviews were conducted with publishers.

For the purposes of this research, we define a publisher as any organization that regularly publishes accounts and analyses of current events using a staff of journalists and editors. The size and reach of publishers in our sample varied (hyperlocal, local, regional, national, or global), as did their production formats (print, audio, video) and revenue models (membership, subscription, and/or advertising).

We use the term “platform” to refer to technology companies which maintain consumption, distribution, and monetization infrastructure for digital media—though each is distinct in its architecture and business model. Google, for example, is a search engine, while Facebook is a social network. In both cases, the majority of each company’s revenue comes from advertising. Meanwhile, Apple makes money from hardware sales, proprietary software, licensed media, and hosted apps. All have used their technology, however, to create products for news publishers to find audiences and monetize readers within their own ecosystems. Our interviews with publishers focused primarily on Facebook (and Instagram), Google (and YouTube), Twitter, Apple, and Snapchat.

Publishers on the End of an Era

In our June 2018 report, we wrote that both platforms and publishers had repeatedly begun to use “words like ‘partner’ and ‘partnership’ to describe their increasingly close relationship.” Still, we labeled this relationship an “uncomfortable union,” given that it was not one in which publishers enjoyed equal power or influence.

There was, in 2018, still hope that working in tandem on ad-based products and initiatives represented an opportunity to make meaningful money—an expectation that existed in spite of publishers’ continued puzzling over the inability to earn consistent revenue from these platform-native products. With no guarantee of return on investment, publishers pushed more and more of their journalism to third-party platforms.

Indeed, the most discernible difference between then and now, observable across historical interviews we’ve conducted over four years, is diminished hope that these platform products might deliver substantive revenue for publishers. This year, one of the most striking themes to emerge from our interviews was publishers’ tendency to answer questions about the current state of their relationship with platforms as if conducting a postmortem.

Phrases we heard throughout our interviews included:

- “It was an era”

- “The platform moment”

- “The platform stuff was a distraction”

- “It was a bubble”

- “The scale game is over”

- “Post-scale world”

Already, a warning issued in our first report has come true: “If the monetization of material given to social platforms by news organizations does not improve, it will exacerbate the crisis in sustainable journalism at the local and regional level. If the tools and design of platforms do not have civic purposes as well as commercial purpose, this is an inevitability rather than a possibility.”

A broken bargain

When publishers refer to the platform era, game, moment, or bubble, they are describing a simple equation that was, until very recently, the platform promise: The platforms had audiences in the hundreds of millions and billions, and should publishers choose to publish their content through platforms’ publishing products—placing ads against that content—the unrivaled number of eyeballs would bring publishers a level of revenue that made it worthwhile to forfeit the direct editorial control and audience relationships that publishers now understand to be key to their success.

The era was all about scale. For publishers, it meant putting platform demands first. Facebook, in many ways, defined this era. It was the platform that most aggressively laid out the promise of massive exposure—and advertising revenue to follow. Though initially the vehicle was Instant Articles, Facebook continued to “pivot” to formats, like video, through which it might still deliver on the basic premise that had been set out.

It eventually became apparent to news organizations that even with upfront cash deals to use Facebook products or create content for them, in the cases of Live and Watch specifically, there was little meaningful money to be made through these “partnerships.” One publisher said, “The reason why publishers and these platforms got into bed with each other originally was that there was a basic bargain”—publishers would provide content in exchange for audience and, by extension, revenue—but “the bargain has broken down.”

Then came Facebook’s 2018 News Feed algorithm change to deprioritize news. While publishers were still puzzling over issues like a lack of robust and reliable audience data from Facebook, the severity of the “Facebook-pocalypse” made clear the worry was no longer that publishers couldn’t quite “see” their platform audiences, it was that huge chunks of those audiences could disappear overnight.

“Eighteen months ago, Facebook sent somewhere between 35 and 45 percent of many of our sites’ total visitation. In that period of time, it has gone from that to seven percent,” one publisher told us in early 2019. “It’s just, the bottom fell out.”

Stories like this one became commonplace. For example, in June 2018, Will Oremus reported that Facebook traffic to his (then) publication, Slate, had “plummeted a staggering 87 percent, from a January 2017 peak of 28 million to less than 4 million in May 2018.”

Though the algorithm change occurred a full year before our latest round of interviews in early 2019, it remained top of mind for a majority of our interviewees, almost as if it had confirmed the death of a broken model. One executive reflected, “Certainly the era of high growth, traffic growth, and just continuing to reach new scale is over. Everything that Facebook has done for us—I think in some ways we took for granted, but also just believed that it would be there. And when that ended, there was a little bit of a reckoning.”

The emergence of a ‘post-scale world’

Language situating a platform era or moment in the past should not be taken too literally, of course, especially given that platform companies (namely Facebook and Google) have too tight a stranglehold on the information ecosystem for publishers to realistically abandon them. That being said, underwhelming return on investment from collaboration with platforms finally led publishers to definitively adjust their priorities.

One person told us, there’s “less optimism around what the platforms can deliver for us” and “a lot less trust in Facebook, specifically.” Another said that the “little glimmers of hope” that remained last year have given way to “the recognition that you shouldn’t be too reliant on [platforms], and that any hope of having any kind of direct commercial benefit from them is probably misguided.”

While in past interviews publishers spread their agenda, and were much more willing to overhaul parts of their businesses in line with platform maneuvers, our conversations were much more streamlined this time around. Publishers mostly talked about two areas of focus: controlling their own revenue models and putting audiences first—platforms second.

Reclaiming Control of Earning Potential

Interviewees across the board talked with more urgency about the need to “stand on their own two feet,” and spoke assertively about “standing up more for themselves” and “calling [platforms’] bluff[s]” instead of shapeshifting in tandem with the whims of tech companies as many had previously.

Publishers are convicted in their efforts to wrestle back control of both how they publish and how they bring in revenue. Specifically, this has meant a renewed focus on their owned-and-operated properties, precisely because they are the only places where they have control over audience experience, data, and revenue.

Diversification across publisher properties

While the term “diversification” is one that has cropped up repeatedly over the years, in past interviews it was most commonly used to reference diversifying platform strategies—as in, not putting all of your resources toward one platform or platform product.

More recently, however, publishers spoke of diversification almost exclusively in the context of exploring the variety of ways they can squeeze revenue from their own properties: reader revenue (memberships or subscriptions) and new products to drive that revenue (newsletters), events, branded retail products, sponsored content, affiliate links, agency services, and, yes, advertisements. While the scope of such diversification varies greatly from one outlet to the next, many interviewees repeatedly described a concerted drive to identify a meaningful mix.

A digital director from one organization told us:

“The basic premise of platforms for publishers has changed significantly. The second-order effect of monetizing traffic that came from posting your story to Facebook—this past year has proven that that model cannot sustain. There’s no way that any publisher who is reliant on Facebook, and increasingly on Google, will have a sustainable business model. There’s no correlation, in almost every case, to actual money. A digital media brand that relies on advertising is almost impossible. Almost zero chance of succeeding today.”

Reader revenue reigns

Reader revenue is a crucial part of the diversification mix and has only continued to gain traction. Even among the 12 outlets whose distribution strategies the Tow Center has tracked since 2016, the three digital natives—BuzzFeed News, HuffPost, and Vox—have all launched membership initiatives in the past year.

(L–R) Membership-based reader revenue initiatives introduced at BuzzFeed News, HuffPost, and Vox in the past year.

Subscription and membership models are poised, publishers hope, to give them control over their route to sustainability and insulate them from the platforms’ often-experimental changes (algorithm shifts, abrupt pivots in format priorities, withdrawal of payments, etc.). There were some encouraging signs in this area.

For example, an interviewee from a relatively young, membership-funded nonprofit described how their outlet had been “insulated” from the most damaging repercussions of major platform shifts because “diversification or diversity has always been an important part of our DNA both on the audience acquisition side and on the revenue side.” This, they contended, “probably has a lot to do with buffering us against a lot of the dramatic changes that other publishers are seeing.”

One person from a membership-funded outlet argued that the continuation of this trend seems inevitable:

“It’s much clearer to everyone that . . . the end game has got to be sustainable readership. If you don’t have a revenue plan—beyond ad impressions and display ads—that is trying to move all of that reach into something more substantive in terms of readers giving [money] to you, whether it’s subscription or through donations, then what’s the point?”

Publishers describe a heightened bar for partnering with platforms

Those publishers who have taken steps toward becoming more self-sufficient claim to be far more cautious about ceding power back to platforms by (re)entering into partnerships. “The barrier to entry is higher because we have a general sense that the more we control our own fate, the better,” one said.

Another interviewee described “control” as being central to a “robust review” of their outlet’s use of platform-native products: “A lot of it was really about just recognizing what things were within our control and what things weren’t.” Conducting this review, they continued, “led to a natural shift away from a lot of the collaboration that we have done with Facebook previously. And as Facebook sort of fell in the industry, there was less focus on building things on Facebook and thinking about that as something that was a key part of our focus.”

As publishers better solidify their own needs and priorities, they are also able to identify whether, and which, platform products are a good fit. Time and again interviewees described being more circumspect in their platform dealings, outlining a requirement for platforms to reach a far higher bar before they will enter partnerships or opt in to third-party product solutions.

Recurring reasons for this new approach can be broadly grouped into four categories:

- Diminished fear of missing out

- Years of underwhelming return on investment from platform partnerships and products

- Deeper knowledge about the considerable ongoing costs of integrating with and supporting third-party products (e.g., engineering costs, etc.)

- New and incompatible business models

1. Publishers feel less FOMO about platform opportunities

Previously, there was a strong fear of missing out among publishers that could only look on enviously at those who got the earliest opportunities (sometimes coupled with financial incentives) to partner with platforms on glitzy new products from Snapchat Discover to Facebook Instant Articles. This was particularly palpable during our earliest interviews in 2016.

Now, however, concerns about feeling left out seem to have all but disappeared. In a surprising turn of narrative, the most optimistic of publishers with whom we spoke in our latest interviews tended to be those working at outlets that were long left out of, or had managed to limit their reliance on, products from third-party platforms.

In our earliest interviews, publishers either felt like haves or have-nots, as smaller, nonprofit, or local newsrooms felt excluded from platform relationships, products, or initiatives.

While many of those outlets that were overlooked in years past couldn’t have anticipated the recent platform turn toward an all-in effort funding local news, some described the fallout of the platform-publisher relationship as one mess they didn’t have to clean up. One publisher suggested feeling spared, saying, “We didn’t have money to throw at it. In this case that worked out because . . . we didn’t see some of the higher returns that some of the other outlets did that ended up informing larger overall strategy and how dependent they got on the platforms.”

Another publisher said there was a time when platforms were the “end all, be all,” adding that “in the past, me and other publishers, especially smaller and local ones, we all wanted better relationships with the platforms. We got frustrated when they were unresponsive. I think we all realized that it’s so unpredictable, and that you can’t rely on any one platform and need to diversify.”

2. A far greater need for evidence of ROI

Stung by years of underwhelming return on investment (ROI) and unfulfilled promises of dollars tomorrow, many publishing executives told us they now require far more compelling evidence that platform partnerships will be fruitful for their businesses. As one local publisher put it, “A year ago . . . [our attitude was], ‘Hey, why not? Let’s give it a shot. [It’s a] 50/50 call, but let’s find out.’ I would say now somebody would have to show me pretty clearly that the benefit was likely, rather than 50/50, for me to make the change.”

One person from a major global news outlet said their “very sensible approach to the platforms” boiled down to one simple question: “What are we trying to achieve and how does each platform fit into that or does each platform fit into that? If they do, let’s partner with them; if not, let’s not waste our time.”

Another person from a local nonprofit was even more specific about their requirements: “If we’re having a conversation with a platform that does not involve revenue or retention, it’s not a conversation that’s worth having, to be honest.”

3. The cost of supporting underwhelming third-party products

Many of the most prominent platform-native news products have been around for some time. Apple News, Snapchat Discover, and Facebook Instant Articles launched in 2015, while Google AMP arrived a year later.

Years of experience with these products have taught publishers that the ongoing costs of integrating platform products extend far beyond the initial outlay for joining. Multiple interviewees identified this as a major consideration when deciding whether to adopt new platform products or continue to use existing ones.

One publisher shared their experience dealing with the expensive, time-consuming effects of juggling multiple platform products: “We redid our [website’s] article page last year, which was a huge undertaking. After we finished rebuilding the page on our site, we had to rebuild it on all of these other platforms. It probably took us two months to rebuild our template on Apple. It took us two months to rebuild Google AMP.”

They continued, “In any project you undertake, each of these platforms adds complexity and development time. Complexity requires people. It really is just about trying to figure out if the ongoing costs of participating are worth the returns.”

This publisher, who was assessing the extent to which platform products could figure into their outlet’s upcoming paywall, described the stages of their platform integration in recent years as: 1) “initial effort” 2) “limping along” and, finally, 3) a “new lens”—through which they could assess the business case for continuing to invest resources into these products.

“We have years of data, so we look at the monetization of the platform and we look at the cost to continue to participate. Because we’ve gone well past the initial effort, and then we had several years where those things just kept limping along. Now we’re looking at all of that with the new lens of: How will this play into or does it play into our consumer strategy, and where can that be a benefit or a drawback to us?”

4. New and incompatible business models

Platform-native publishing products from the most ubiquitous companies like Facebook and Google have long been optimized for keeping users on-platform and serving digital ads quickly. So, in other words, these news outlets are pivoting to business models with which those platform products are not necessarily compatible. For example, one local publisher described how a shift to reader revenue had made him more cautious about being talked into using platform products:

“Now that we’re doing so well with membership, and we see how crucial that [model] is to our future, I’m wary of anything that could make that unstable at all. And so there’s more of a barrier for the platforms to hit for me to make a change. You’ve got to prove you’re not gonna blow this up, because this is really working for us. And before [adopting a membership model] there was nothing that was working so well that the risk was that large.”

This person added that, having abandoned AMP and Instant Articles due to their incompatibility with the business, “There is something lovely about feeling like I have much more control of my own fate than was the case before.”

This, of course, is an area to watch closely, as platforms have rolled out products for reader revenue-supported publishers such as Subscribe with Google and a paywalled version of Facebook Instant Articles. Publishers interviewed did not not yet have enough experience with these products to provide an assessment of their utility. For now, it’s fair to say that platform products, including these newest ones, are seen as tools in a larger toolkit. They may be one mode to a multi-pronged end for publishers, with any resulting revenue earned considered a bonus.

Some publishers still don’t enjoy the luxury of refusing help or ‘going it alone’

Publishers’ flexibility in relation to their use of platform products continues to be largely determined by their business model and the health of their owned-and-operated properties, as has been the case since our earliest interviews. Publishers eager to be less reliant on platform products shared different obstacles holding them back, ranging from higher CPMs on Instant Articles or larger audiences on Apple News as compared to their own mobile or web sites.

An interviewee who moved from a publication focused on advertising and scale to one operating a membership model described the extent to which these contrasting business models impacted the importance placed on following the tech platforms’ lead:

“All I did [before] was talk to the platforms all the time. [. . . ] I don’t want to undermine how important they are because we do get a fair amount of traffic from them. But they don’t lead our strategies in the way that they used to at [the previous publication]. They’re a soccer ball on the field and people run with it in one direction and everybody chases it. Everybody’s playing soccer and we’re watching, and have vested interest in the game, but we are not running after the ball. We’re doing our own thing on the side.”

Some interviewees described this ongoing attachment as a “continued dance” and “never-ending game.” An audience engagement manager captured the prevailing mood as “skepticism rather than optimism, but not a retreat.”

While better-resourced publishers intent on shifting revenue strategies away from platforms reported changes in the nature of their interactions with previously high-touch platform representatives, describing them as “less frequent, less urgent, and less tense,” a social media manager from a local publisher with an ad-heavy revenue model outlined a decidedly different experience:

“It just frustrates me because I feel like they’re giving us just enough where we’re not fully letting go and trying to pursue a different strategy. They’re feeding the beast just enough to keep [us] hooked onto Facebook. So here I am with a social media team that is getting smaller and smaller every year. And my Facebook traffic keeps shrinking, but . . . I’m still forced to make sure they do spend a ton of time posting to social media . . . when there’s a million other things that maybe we could be experimenting with, or finding time for some innovation, or freeing that team up for more strategic initiatives instead of just posting to Facebook all day. But we’re hooked just enough where I can’t tell them, ‘No, you don’t have to post to Facebook all day, every day anymore.’”

Similar sentiment was voiced by an interviewee from a digital native still reliant on dwindling eyeballs and therefore ad revenue from Facebook, who said, “Before, we were still seeking a partnership . . . but now it’s like we’re wounded animals and wondering if they’re going to shoot us or try to give us just enough medical help to keep us alive so we can continue to serve them.”

Publishers ramp up skepticism about platforms’ commitment to journalism

Despite—or possibly because of—the introduction of numerous, high-profile initiatives to fund news, we heard stronger sentiment than ever that platforms do not have journalism’s best interests in mind and cannot be trusted no matter what they promise.

When it came to assessing platform motivation, Facebook was the subject of particular scorn, due in large part to its ubiquity and tendency over the years to pivot its product focus far more often than other platforms. In fact, many complaints we heard about “platforms” boiled down to primarily a dissatisfaction with Facebook. “Facebook have never really been genuinely engaged with the idea that news has any value for their platform. I think they’re really focused on [giving money to] local news in the US because that’s the political hot topic [right now],” one person said. Another called their recent journalism efforts “PR.”

The precarious nature of direct payments from platforms—whether in the form of grants from Facebook or Google to smaller newsrooms, or seven-figure deals to larger newsrooms to use products such as Facebook’s News tab—was another area where multiple interviewees claimed to have become more clear-eyed, typically characterizing them as welcome but unreliable bonuses.

An interviewee whose organization had recently been in receipt of one such offering described their reaction as, “This is fantastic. But also this is not going to save our business. And I can’t count on this to renew.”

Yet another publisher representative from a national newspaper conglomerate said, “We absolutely need the money that they’re giving us to innovate, or have a shot at growing our audience, or even figuring out a path to a subscription strategy. So, I am thankful for the money, but I think there’s also some resentment . . . from people who work in [our] social media [departments] who are like, ‘I’m just tired of being at your beck and call’ kind of thing.”

The Shifting Platform-Publisher-Audience Dynamic

In our first report from this research project, published in 2017, Carla Zanoni, then of The Wall Street Journal, said that successfully utilizing platforms hinged on “your ability as a publisher to engage with [the] audience and build a long-standing relationship that extends beyond the platform.”

But developing a new audience on-platform, and figuring out how to monetize that audience, meant grappling with the question of “who owns the relationship with the user,” and “who controls that relationship and that data,” said Cynthia Collins of The New York Times.

Nearly two and a half years ago, these were prescient points—especially at a time when, as we noted then, “scale is everything, from number of likes and shares to ultimate reach.” Many publishers were fixated on how to access a huge universe of potential readers at the expense of their most loyal ones. According to a local publisher, that meant chasing trending content and operating in a way that left their local readers feeling “distant.”

By the time we published our second report in June 2018, publishers were reckoning with the ramifications of treating audiences not as individuals, but as a number.

One publisher told us then, “News organizations lost the idea of the audience as a real user, somebody that you had to work to acquire. Now there is this turn to understanding that our mission needs to be stronger. We need to be more respectful of our audience, because we need to have a direct relationship with them. They are not just a couple of billions that show up in analytics, but real people who care about news or who want a reliable and trustworthy news experience.”

Numerous interviewees in this latest round suggested that the drastic withdrawal of Facebook traffic, and associated “end of the scale game” that was just beginning to emerge in our 2018 report, led to one of the most significant learnings from the fallout of this platform “era”: Anything that distracts a publisher from focusing on their most loyal audiences is a losing strategy.

“The platform stuff was a distraction. It was a good lesson, an objective lesson in: Listen to your audience,” one publisher said. Another told us that the immense pressure and urgent stress “really forced us to focus on the core—the people that did continue to come back—and to think about how we shift our thinking from just pure scale to really engaging with those core loyal users.”

One publisher nicely summed up their (re)prioritization of audiences as “seeking you out in some way, versus just running into you.” They added, “If you rewind three, four, five years ago, the drive-by audiences, the scale that you could drive through these platforms, in some ways could blind you to the fact that you’re not necessarily building your own community or audience. It really changes the strategy, which I think is a good and healthy thing for brands.”

Platforms are now (generally) secondary to audience when making editorial decisions

In our 2017 report, we noted that journalism with high civic value was discriminated against by an ecosystem that favors scale and shareability. Still, as platforms introduced new formats for publishing, which happened at a particularly rapid pace back then, publishers adopted them quickly. And this decision began to affect editorial strategies with questionable results. One publisher told us then, “We are telling stories that other outlets aren’t telling, which is almost to our detriment in the world of viral news. When it comes to the way Facebook and Twitter currently surface trending content and breaking news, it’s not about the story that no one has. It’s about the story that everyone has.”

Over the years, platforms continued to shape both the style and substance of publisher content. As we wrote in last year’s report, there was still an appetite to “play” with platform formats and products, and for experimentation, as publishers were still trying to figure out editorial that would perform on platform and count as important journalism. One digital native publisher asked then, “How do we match up what we consider important journalism with extreme audience optimization”—or, in others words, platform scale. “Those things don’t always click.”

The answer, it turns out, is that “those things” seldom do. In an effort to untangle editorial decisions from platform scale strategies, in our most recent interviews publishers described varying degrees of liberation. One publisher pursuing reader revenue said their editorial thinking is now shaped “more around our audience strategy and who we’re trying to reach. The platforms are secondary.”

Another person said they are “thinking politically and ambitiously about what we need to do to get our audience. What should we be focusing on as topics or viewpoints for our editorial brand?” One interviewee, based at a local, subscription-based outlet, described the win-win of adopting a stronger audience-centric approach, saying, “Our top subscribers read stories that are really local. They are generally investigative or enterprise. It actually is the kind of journalist’s dream of what you think people want from a newspaper.”

Connecting the dots between the triumvirate of business model, audience, and editorial, an interviewee from a global publisher with a membership model argued that their model enabled them to prioritize quality over quantity:

“If you need to create highly engaged users with your brand . . . it means you can take different decisions about the content you commission and you can be much more focused on building quality and trust, rather than creating content that drives one-time readers. If your focus is on engagement to drive reader revenues, it changes your approach to the sort of journalism you’re commissioning—maybe less stuff, but publishing better stuff. I think it’s quite a healthy change really.”

At times, contrasting responses from interviewees brought the connection between business model and editorial freedom into sharp focus. One local publisher described how a change in business model, pivoting away from digital ad revenue, had directly impacted their willingness, or need, to regurgitate viral stories:

“The truth of the matter is, when you’ve decided membership and events are where you’re going to make 80 percent of your money, then virality is only of some [limited] value. It’s limited because you get a bunch of ad revenue out of it but no members, or the likelihood is it’s a story that would go viral nationally and thus you’re not going to get a lot of [local] members or anybody to come to an event.”

On the other hand, a local publisher that remains tied to platform economics and digital ad revenue described a continued focus on trending stories in pursuit of page views. They described feeling “still stuck on the Facebook and Google train,” and expressed frustration that corporate pressures to hit a “massive page view goal” dictated that they “have a whole team of people that do nothing but stare at CrowdTangle all day, see what’s going viral on Facebook and then aggregating that content. We’re doing follow-up stories on what’s going viral and what’s trending, which kind of dilutes your local feel.”

This person shared a particular anecdote that illustrates how top-down directives to pursue scale for advertising revenue resulted in cutting smaller, but potentially monetizable, beats. Citing their publication’s food section, the interviewee said, “We looked back and thought, ‘Oh my God, we cut all these beats purely off of one factor, and that’s page views.’ We didn’t consider, ‘Do they drive loyalty and retention? Do people subscribe off of these stories more than the other ones? We don’t know. We didn’t do the analysis. We don’t have the data. We weren’t tracking it.”

They went on to describe how their shrinking editorial staff had resorted to taking matters into their own hands, conducting experiments to try and ascertain “what verticals may drive more repeat visits and then maybe drive more conversions in the long run.”

Platform products as marketing vehicles to capture readers atop the engagement funnel

Facing the end of the scale era has forced many publishers to take a more nuanced approach to audience data. One publishing executive described the change in thinking as follows:

“We used to be more of a one metric-focused company. It used to just be about, ‘How many visitors do we have?’ and that’s all we cared about and talked about—to really thinking about them in cohorts, thinking about engagement, and thinking more deeply about how you move people from one place to another. It is going from one metric to many metrics.”

Another publisher said, “Now I’m much more focused on: What is the loyalty behind those different audiences? How often are you coming? How many pages per visit are you seeing?”

Multiple interviewees described segmenting their audiences based on their levels of engagement with the brand, categorizing via labels such as “drive-by,” “grazers,” “most loyal fans,” and, of course, “subscribers.”

In this vein, as more and more news organizations turn to direct contributions from audiences in the form of memberships and subscriptions, many interviewees from various newsroom types invoked the marketing language of “funnels” with remarkable frequency when describing a new platform-publisher-audience dynamic.

It was in this context that they frequently returned to talk reminiscent of our earliest interviews, citing platforms as “distribution channels to put content in front of audiences.” The difference now, however, is that instead of just spraying content every which way and hoping for eyeballs, publishers are forming strategies around how to hook readers at that point of platform contact and reel them in, down the funnel.

Most interviewees referred to platforms in terms of their position at the top of the funnel because of their unmatched reach and centrality to so many aspects of people’s everyday lives. One said their newsroom “talks about the platforms as a form of acquisition.”

An audience manager from a local nonprofit told us, “The platforms are a big part and will be a big part of [reaching people] as long as people are there living their lives, getting information, conversing about the information that they’re getting with their friends and families and hopefully with us. It’s simply that we need to figure out and be strategic about the next steps.”

Those next steps after discovery—at the top of the funnel when audiences are exposed to and become aware of a brand—are engagement, conversion, and retention. Another person said, “We are increasingly obsessed with what happens in the middle of the funnel,” referencing the phase of engagement when audiences can begin to develop a habit and brand loyalty, before conversion, which happens at the bottom of the funnel when they decide to support the outlet by becoming a subscriber, member, or donator. Having converted users, the final stage in this model is retention.

This process of engaging, converting, and retaining audiences demands considerably more of news organizations than simply inducing readers to click, share, or react to a post on a third-party platform. It was in this context that some interviewees lamented how platform products redefined the term “engagement.” Referencing CrowdTangle’s metric of “overperformance” (based on Facebook interactions), one complained that they see stories “quote-unquote over-perform on Facebook all the time and all they are are people sharing things without reading the stories.”

An audience manager from a local nonprofit went further, speaking in depth about the importance of reclaiming the term so that it centered around the publisher-audience dynamic rather than the platform-audience dynamic:

“The overarching thing for me is the importance of engagement. I really think it was such a bad trend where newsrooms were obsessed with ‘engagement’ and kept talking about it in terms of all these social interactions. Those were really metrics that were helpful for these platforms in terms of them trying to build their own platforms and ensure their users were addicted or obsessed with those apps, but not super helpful to publishers in the long run. I think finally publishers are looking at that word ‘engagement’ and understanding that it’s much more about a relationship with a reader. For that to exist you have got to think beyond an interaction or platform. We have to think about retention and where do I move next with this person and how do I keep in contact with this person.”

Ethics

In our previous rounds of interviews, when asked about the ethics of partnering with platform companies, publishers did not draw a connection between broader platform controversies and their own newsrooms. This time, however, as negative press about platform companies is front and center in the public consciousness, interviewees described pushback from both their newsroom employees and readers about the potentially problematic nature of their alliances with platforms.

Guilty by association?

Growing platform scrutiny—by journalists, legislative and regulatory authorities, and even the general public—has intensified significantly since our research began. Platforms have become hotbeds of rampant misinformation, hate speech, extremist viewpoints, and foreign interference. Further, platform companies have endured a host of security and privacy breaches, which compromised user data. Calls to break them up—both inside the US and outside—are growing louder. Less than 30 percent of US respondents said they trust major technology companies “most of the time” or more, according to a 2018 Pew Research study.

In this environment, it is unsurprising that some interviewees reported pushback from their audiences about their complicity in continuing to use of these platforms. One publisher said, “When Mark Zuckerberg testified before Congress we had a ton of stories about that and we’d post them on Facebook. We’d see our readers saying, ‘We don’t want to read you on Facebook’ or ‘How is it that you are doing this reporting about some of the unethical things that this company is doing but you’re still using them as a platform?’”

They added, “Our membership group . . . [moved] off Facebook because people didn’t want to have to join Facebook or they had deleted their Facebook and didn’t want to have that as a barrier to interacting with this membership community.”

Although in this case the publisher did take action in response to audience feedback, others have not felt they had that luxury. Another interviewee noted that while they are aware of audience concerns, platforms remain vital distribution mechanisms for reaching those very readers with need-to-know information. “We really want to be using them as little as possible because of all the criticism,” this person said, “but we’re definitely not in a position where we’re going to turn away from it because it does so much. I think we don’t really see an alternative to using them.”

There were rumblings of concerns within news organizations, too. One social media editor said of journalists in the newsroom, “It mostly comes up when I ask for them to do something and they’ll say, ‘Is anything changing because I’m uncomfortable being a part of this.’ They have to login through a Facebook account and there’s certain people who don’t want a Facebook account because of what’s going on.” But, they said, the conversations end there, and no action is taken. “Facebook is not as popular as it once was but it still has millions and millions of active users. We’re still just going until something explodes.”

Beyond Facebook, another interviewee wondered where the line could be drawn, noting that scandals are not exclusive to any one platform. “If you do walk away from Facebook, are we then saying it’s worse than things like Reddit, which has its problems, or Twitter, which certainly has its problems, or things like Apple, which is a little bit evil, too? What about Google? Google is terrible with fake news,” this publisher said. “We can’t just disappear off the internet. . . . We talk about it but I don’t know how confident we are that we’re going to do anything differently.”

Still, this person continued to grapple with their complicity in drawing audiences back into platforms. “It’s weird because you have a business team that has technology reporters who delete Facebook,” they said. “If we post our content on a company site that is not good to people are we not encouraging people still to use that product? Facebook is bad but this is still a place where you can find us. We’re encouraging people to use it and we report on how bad it is, yet still post on it.”

Others voiced an alternative perspective. For example, one interviewee spoke with strong conviction about the need for accountability journalism about tech platforms to reach the users of those very platforms:

“What we haven’t done is step back from publishing journalism on [Facebook] and the really clear reason for that is it would be absurd if we were publishing news stories about the relationship with Facebook and Cambridge Analytica and all of the issues that go along with that and the people who were using that platform weren’t able to read that journalism.”

On accepting ‘free’ platform money

The publishing industry as a whole is grappling with whether to accept the hundreds of millions of dollars pouring in from Facebook and Google journalism initiatives.

One person whose cash-strapped news organization had received a large sum in free Facebook ad credits described their attitude as, “Of course we’re going to take your money, because without it we wouldn’t be able to innovate, and we wouldn’t have as many opportunities as we have right now.” It’s a sentiment that recurred often across our interviews.

One journalism funder who works with both Facebook and Google at first told us flatly: “Take the money; it’s money.” But as they continued, they began to wonder about the optics and possible ethical implications of taking platforms at their word that these supposed philanthropic offerings come with no strings attached:

“If it was tobacco money or alcohol money, then don’t take it. Oil money or . . . from a gun company, there’s an ethical thing about that. Maybe some people would argue that Facebook is becoming that, especially just this week with this thing they installed on people’s phones to track teenagers’ activity and pay them for it. I mean, I guess they told people they were doing this and had to obviously get them to install it on their phone. It’s not like they’re giving malware.

“[But] it doesn’t look great. Is Facebook linked with tobacco or gun companies just yet? I mean, if you truly think that then maybe don’t take the money. Some people on our board have questions like, ‘Are we sure we want to be working with Facebook?’ It’s not always like that, but then, in the end they’re like, ‘But they’re offering us [millions of] dollars. Yeah, I guess we should take it.’”

The funder concluded, “You don’t want to be reliant on them. That would just be my caution,” adding, “we can’t build a business around having these tech companies fund journalism. That’s what concerns me when some people say they should give us more money and billions to journalism. Is that their role, to be the subsidy for journalism? That seems wrong somehow.”

The Platform Response

With a few exceptions, the platforms we spoke to agreed that platform-publisher relationships have become more strained in recent years. One platform representative said, “I think there’s less optimism, and there’s more frustration. I think there’s more strategic misalignment which makes it far harder for both parties to try and come together [so that it] doesn’t feel like one is benefiting off the other.”

Another one told us, “I think in 2018 the relationship became a little bit more antagonistic and as a result of that a lot of my colleagues who were doing partnership management with news publishers were responsible for a little more sentiment management than pure marketing.”

A move toward offering subscription ‘solutions’

Unsurprisingly, though, platform companies have continued to develop a range of products and services to insert themselves into every step of publishers’ newest focus: reader revenue. The Google News Initiative website has a page dedicated to showcasing how Google’s “set of technologies and solutions is designed to help news publishers engage users across the funnel,” promising to “Expand reach,” “Drive conversions,” and “Engage subscribers and members.”

At the bottom of the funnel, the big three (Apple, Google, and Facebook) all claim their solutions can take “friction” out of the final step of “conversion.” Apple has rolled out Apple News+, a subscription service through which participating publishers split what’s left of the 10 dollars a month users pay once Apple takes its 50 percent, based on readers’ dwell time; Google rolled out Subscribe with Google (for which it takes a 5 to 15-percent cut); and Facebook has launched a paywalled version of Instant Articles.

In a June 2019 blog post, Facebook product manager Sameera Salari announced the company’s Instant Articles paywall product had been opened up to “all eligible publishers.” Salari’s post, titled “Supporting Subscriptions-Based News Publishers,” outlined numerous ways in which Facebook products could be used throughout the process of converting readers into paying supporters. One new product being tested, named News Funding, was said to be “focused on helping publishers build closer relationships with their readers” and “designed for local and niche publishers interested in using a Facebook-based membership model.”

Summarizing, Salari wrote that “Facebook Analytics can be particularly insightful for publishers because it provides omni-channel, people-based insights throughout the funnel—from an article read to a subscription sign-up. This means publishers can measure the behavior of their audiences, with multi-surface users de-duplicated, across Facebook, Instagram, and publishers’ mobile apps and websites.”

Platform news strategies mature

Big tech platforms have have run into major issues around distributing and moderating news content on a product-by-product basis, often without top-down strategies. Recalling an incident in 2015, one platform representative told us, “I remember being in the room with 200 people and they were from all over different bits of [the company]. Someone said, ‘Everyone who works with The New York Times, put your hands up.’ There were like 20 people on different teams and none of them had spoken to each other.” A representative from a different platform said, “It wasn’t a centralized news team. Pre-election, it was fragmented.”

In the last two years, platforms have made efforts to concentrate their news efforts under cohesive overarching strategies. In 2017, Apple hired its first editor-in-chief and Facebook appointed a new head of news products (who has since left the company). In January 2017, Facebook introduced the Facebook Journalism Project, a program said to be built around three broad pillars: collaborative development of news products, training and tools for journalists, and training and tools for an informed community. In 2018, Google announced the Google News Initiative (GNI), an umbrella program under which all of its news-related efforts would live. Google’s claim that it would commit 300 million dollars to journalism via GNI was matched by Facebook in January 2019. These transitions have had mixed results, with one former platform employee lamenting “a top-down entity that wasn’t there.” She said of the platform’s news efforts, “There was broad commitment absolutely. Do I think that there was consistent commitment from everybody on a specific point of view? Absolutely not.”

As teams that focus on journalism products and initiatives have grown, platform employees with newsroom experience have helped their companies develop better approaches to publisher relations. As one such employee said, “If you’ve always worked in news, it’s hard to understand all of the knowledge that you’ve built up that people who don’t work in news don’t have. I think that maybe being able to give that context earlier to senior people would have helped us a lot.”

Many of the platform representatives we interviewed described productive conversations with members of senior management eager to learn more about the inner workings of journalism organizations, a potentially positive sign for publishers. Others however described the missions of news teams as being at odds with those of their companies at large. As one interviewee said, “There’s a small group of people that have all come out of journalism that see themselves as almost like Robin Hood.” In general, top-level interest in journalism seemed to be tied to how much it related to each platform’s mission and bottom line.

The tricky task of categorizing news

Platforms on which publisher content coexists with brand- and user-generated content have long struggled with defining who counts as a publisher and what counts as news. Describing her past experience on a news product team, one former platform employee said, “No one knows what news is. Is it defined by something that a top 50 publisher has marked [as such]? Is it anything from The New York Times? They have a recipe section that’s obviously not news. Your mom writes some crazy thing about Donald Trump, that’s not news. But if a public figure on [the platform] then writes a post about Donald Trump or they write policy posts, is that news? No one really knew, and that definition shifted wildly over time.”

Platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Google continue to struggle with defining news—not to mention the even more elusive “high-quality” news, for those platforms that use this barometer when curating. When Facebook introduced its News tab in October 2019 the company was immediately criticized for including Breitbart in a section that Mark Zuckerberg had said would be a destination for “high-quality” and “trustworthy” news.

The rise of influencers—social media users with large and devoted followings who often act like one-person publishers—on platforms like YouTube and Instagram only makes such distinctions more difficult. Multiple interviewees were taken aback by the question of whether their platform treats publisher content differently from influencer content. After noting the importance of “authoritative information” for people seeking news, one platform executive told us that ultimately “anybody can be a creator and anyone can be a publisher.”

As the information landscape becomes more complex, optimism around automated approaches to content moderation and curation is waning. Largely inspired by Apple, platforms now see human editors as vital members of their editorial teams rather than temporary fixes to be eventually replaced with scalable alternatives.

One platform representative whose work focuses on curating both news and user-generated content told us, “What we’re trying to do is . . . use algorithms to . . . get as far as possible in terms of the identification of useful information and then have the [human] curators layer that makes the final decision.” Another interviewee said, “I think it’s the combination of human editorial and algorithmic curation working really closely together and aligned behind the same principles that actually produces the best quality.”

The realization that AI will not be a panacea for platform woes has also led to a resignation that platforms will never get everything 100 percent right. As one representative told us, “If I came on and told you we are going to be able to identify all truth and all lies and accurately reflect the entire populations belief about a topic . . . I would definitely be lying to you. This is not scientific. It has to be about some level of judgment and some level of reflection of what we’re seeing on the platform.”

Facebook still takes the most heat

Most platforms agreed that Facebook has the most strained relationship with publishers due to its many broken promises, inconsistent messaging around journalism, and “move fast and break things” approach to product development. As one platform representative said, “I would way rather be working here than Facebook partly because Facebook made such a deliberate move into the news industry and to the flow of information and then kind of screwed it up as royally as they did.”

In 2017, Facebook’s mission changed from “make the world more open and connected” to “give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together.” This led to an influx of company resources to Facebook Groups and to the News Feed algorithm favoring content from people rather than publishers.

One reason many cited for Facebook’s mixed record with journalism is the fact that publisher success is not tied to its bottom line or even its mission. As one interviewee said, “Google has done I think a very clear job of aligning their business incentives with this stuff. They know that the more people search for news the more that it supports their bottom line. If you look at Facebook, what actually drives the core business is the strength of its social grasp. That really relies on people sharing information about themselves to their family and their personal network. So news is a really important piece but it is not something that actually drives core usage or retention . . . News is something that feels like an active responsibility but it’s not necessarily tied to a strict business line.”

One former platform executive told us she thought the Facebook relationship will “get worse for larger-scale publishers who are very vocal and drive the narrative” and “better between Facebook and local publishers,” given that the platform has “pledged and committed to” funding initiatives particularly aimed at offering what we would have once referred to as “have-not” publishers money to flourish outside of the information ecosystem that Facebook itself controls. Though referring to Facebook’s 300 million-dollar journalism pledge, she jokingly added, “I think you need more like 30 billion dollars.”

What’s next?

Platform representatives were cautiously hopeful about the future of the platform-publisher relationship, while staying away from any specific predictions. One former executive summed up the tone of many of our interviews: “I am broadly optimistic but it might be more painful in the interim before we actually get to some alternatives that actually work.”

A few of our more candid interviewees on the platform side shared the sentiment expressed by publishers that the last year felt like the end of an era. One described the future as “highly dependent on whether platforms figure out how to reconcile their needs from publishers with how they incentivize publishers. I think they’re still a bit confused about that and still working that through.”

She added, “I never want to walk into a journalism conference again and see people going, ‘Oh, Facebook Live, we’re all going to pivot to Facebook Live and make lots of money off of it, and it’s all going to be brilliant, and this is the best thing ever, let’s talk about Facebook Live. Or whatever the new thing will be. I think the publishing industry has hopefully got to a point where they are comfortable with putting their needs first rather than having a sense of FOMO.”

For the moment, the “new thing” appears to be platforms’ willingness to directly pay for the journalism they host in their ecosystems. The longevity and success (or failure) of new products like the Facebook News tab will be barometers to watch as the next “era” unfolds.

Conclusion

By Emily Bell

As the first decade of the social, mobile web draws to a close, it is clear that the influence of large-scale technology platforms has disrupted but not reformed the field of journalism. Publisher and platform employees interviewed for this report were in overwhelming agreement that it is the end of an era of hopeful exploration and to the fallacy that scale alone will help create sustainable models for journalism.

This is another way of saying that both parties in this experiment recognize that growth in digital advertising is not realistic, and that if the relationship is to be a productive one it will have to deliver more direct subsidy or a clear path to monetize audiences.

The first five years of developing integrated relationships between news organizations and platform companies has been largely unsuccessful. Newsrooms have not found sustainability, and platforms, particularly Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter, have become synonymous with misinformation and abuse rather than high-quality news and entertainment.

Even in the past year, we witnessed a litany of failures: closures and cutbacks in newsrooms that pivoted to video on the back of false Facebook projections about increasing revenues; a raft of algorithm changes which left news organizations disoriented and platforms scrambling to fix rampant problems with misinformation; and the inescapable fact that while digital advertising revenues boomed for Google and Facebook, they continued a precipitous decline for publishers. Even at the most successful digital publishers such as The New York Times, in late 2019 the percentage of digital advertising as a whole was actually declining, as well as declining in real terms by as much as 14 or 15 percent year on year.