Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

THE CITY OF CHARLOTTESVILLE launched an online survey in March to solicit new names for Emancipation and Justice Parks. Until recently, the two public spaces bore the names of Confederate generals, whose recently unshrouded statues still stand in their respective parks as gifts of the Jim Crow era. Emancipation Park was the site of the August 12 “Unite the Right” rally, during which a man drove a car into a crowd of protesters, injuring more than a dozen people and killing local resident Heather Heyer. A press release from the city invited “the community’s input” on new names, by selecting from a previously approved list or writing in alternatives, and noted that “Lee Park, Jackson Park, and Emancipation Park will not be considered.” All told, the city received more than 7,500 responses to its survey, the vast majority of which were submitted online.

Before August 12, it would have seemed unlikely that such a survey would reach beyond Charlottesville. Since the “Unite the Right” rally, however, the city has been identified as both a symbolic and literal battleground by white supremacists. A FOIA request filed by CJR reveals a number of disturbing racist and anti-semitic survey responses, many of which seem to have been solicited via white supremacist message-board threads and submitted alongside community input. What’s surprising, given the city’s recent history, is that those comments—and the susceptibility of the city survey to racist trolling—received so little coverage from local news.

ICYMI: Photographer behind graphic Charlottesville image recounts near-death experience

The city provided the survey results to Charlottesville paper The Daily Progress, which on April 5 reported the top vote-getters (Court Square Park, Market Street Park, Vinegar Hill Park) and listed “some of the more popular” write-in names (Swanson Legacy Park, Heather Heyer Park, Donald Trump Park). The city also gave the results to Rob Schilling, a former Republican city councilor and longtime host of The Schilling Show, which maintains a two-hour weekday block on WINA, a local radio station. Schilling reported on his site that the survey constraints “did not stop a plurality of respondents from writing in ‘Lee Park.’” He also pointed out that the Progress “completely omitted referencing the 1,822 write-in votes for Lee, as if they never were cast.”

What the @DailyProgress won't tell you. The REAL results of Charlottesville's Park Renaming Survey: Robert E. Lee wins again: https://t.co/PU4XJIEjth pic.twitter.com/6AoY1cGJEB

— Rob Schilling (@SchillingShow) April 6, 2018

The Cavalier Daily, the University of Virginia’s student-run newsroom, mentioned the number of votes for Lee midway through its coverage, and also flagged “community members’ preferred names” under its headline. C-VILLE, the city’s alt-weekly, cited Schilling’s reporting in a news brief. The Charlottesville Newsplex shared top survey responses for each park during a broadcast, then directed viewers to a section of its website where they could review “the full results of the naming polls”—actually a three-page summary compiled by the city.

NBC29 also reported that write-in votes for “Lee Park” eclipsed other top responses. The local NBC affiliate included a response from a city spokesman, who said the name would not be considered because councilors “want to tell a more complete story about Charlottesville’s history and its relationship to race and white supremacy.”

The station, which described survey respondents as Charlottesville “inhabitants,” also included comment from local resident Mary Carey, who filed a petition in February in which she argued that “Emancipation Park” did not adequately reflect the interests of city residents, particularly those of people of color. “I just like the idea of the people suggesting and choosing a name that they would like,” Carey said to NBC. “That’s the way Charlottesville’s supposed to be.” Citizens, she added, got a chance “to make a choice, and to choose what they desire for a park.”

But the survey was not exclusive to city residents. It’s virtually impossible to constrain such a survey by geography. Anyone with internet access—from local residents to Confederate apologists and white supremacists around the country—had a chance to choose what names they desired for Charlottesville’s parks. With few exceptions, it was impossible to tell who had voted for what name, and where those votes might have come from.

In general, local reporters failed to probe the limits of such a survey—what it can tell us, and what it cannot. While decisions concerning Charlottesville’s parks will be made locally, they will play out before a national audience, some members of which have pernicious ideas about who the city should serve.

This survey is open to literally anyone with an internet connection, and is therefore at risk of being hijacked for the agenda of non-city residents.

CHARLOTTESVILLE LAUNCHED ITS SURVEY on March 6. Within days, someone posted the survey link to a Reddit page devoted to former President Barack Obama. “One option is Barack Obama Park,” the poster wrote. “You know what to do.”

Someone replied, “I don’t think we should brigade an online poll intended for Charlottesville, VA residents,” and the discussion seemed to end there. However, the original poster also shared a link on a Charlottesville subreddit. “I’m sure this will go really well,” someone else replied, adding with sarcasm, “Outside parties rarely infiltrate and brigade online polls.”

The survey moved beyond Charlottesville city limits. Confederate Broadcasting—an online radio show with a mailing address in Silverhill, Alabama—tweeted a link to its own website, where it shared the survey link as well as a Charlottesville phone line designated for accepting name suggestions. A DC-based Twitter account named Demography Now shared a link to the survey along with a request that followers “write in the original names”—Lee and Jackson. The same Twitter account also shared a link to a public post on Gab—a social media site endorsed by white nationalist Richard Spencer whose certified users include Christopher Cantwell, a white nationalist who faces felony charges in connection to the August 11 torch-lit march through the University of Virginia.

Several Gab users shared the survey link publicly. One tagged Cantwell’s account in a post, and included a screenshot of the Charlottesville survey with “Adolf Hitler Park for Friendship and Tolerance” written in. Another posted a link to the survey and suggested the parks be named for Cantwell and James Alex Fields Jr., who is charged with first-degree murder in connection to the fatal August 12 vehicle attack. A few people responded to that post with indications that they had voted, and more than a dozen Gab users shared the link.

CJR obtained from the city a spreadsheet containing the responses to its survey. A review of the responses compared to screenshots posted on Gab and comments on the 4Chan message board suggests a number of people with no discernible connection to Charlottesville used the survey as an opportunity to troll the city—with names that champion Cantwell, Fields, and Hitler; disparage Heyer; or attack members of the city council. A few responses, one of them pledging an “ethnostate,” contain references to “your city”—a fair indication that respondents don’t live in Charlottesville.

At least one response included a warning about the survey itself. “This survey is open to literally anyone with an internet connection,” a respondent wrote, “and is therefore at risk of being hijacked for the agenda of non-city residents.” With the exception of this story, from NBC29, CJR found no such warnings in local news coverage promoting the survey.

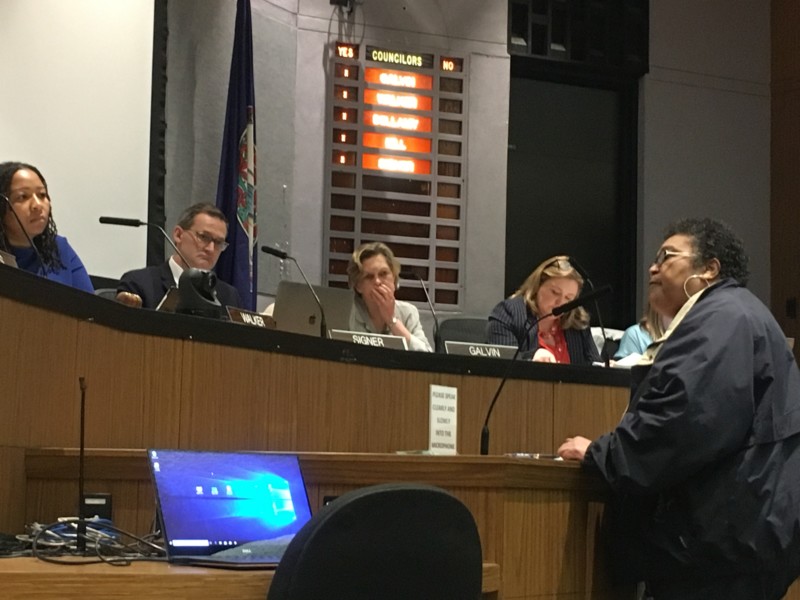

Charlottesville resident Mary Carey (right, standing) addresses members of city council this week, at a meeting in which the survey results were discussed.

CJR REACHED OUT via email to six local news outlets that covered the Charlottesville survey. Of those that responded, none were aware of links to the city survey being shared on venues like 4Chan and Gab. Asked whether local news media should be concerned about covering responses to a local survey without knowing who or where such responses come from, the three outlets who responded offered three different answers.

“I would think local government should be more concerned about having such surveys and not limiting them to residents,” says Lisa Provence, news editor for C-VILLE. (Disclosure: I am a former C-VILLE news editor, and my wife manages a business magazine published by C-VILLE.)

During the week she wrote her news brief on the survey, Provence contributed more than 2,000 words to an issue of C-VILLE, on subjects including a local screening of Katie Couric’s Re-righting History documentary about Charlottesville’s monuments and a legal proceeding involving Jason Kessler, the Charlottesville native who helped coordinate “Unite the Right.” Had she covered the survey in-depth, Provence says, “where the results came from would have been a pertinent question to ask.”

Rob Schilling, the radio-show host who criticized The Daily Progress for omitting “Lee” votes in its reporting, tells CJR that local journalists “should be more concerned about the city and some media outlets suppressing the top vote-getting names for the parks, and for the city’s refusal to consider those names.” Asked whether the survey could be a meaningful indicator of the preferences of Charlottesville residents, Schilling says residents of Albemarle County “should have a say in making the decision,” owing to the county’s revenue-sharing agreement with the city.

Desiree Montilla, a reporter for the Charlottesville Newsplex, suggests that former Charlottesville residents might still feel invested in the city and compelled to vote. Local news coverage “should come down to covering the patterns seen from the overall response of the survey,” she writes. “Looking at it from the reporting standpoint, we are covering the choices from the community.”

But that’s not how the survey worked. The city provided details in its council agenda that detailed the repeated use of some IP addresses—15 in total, which accounted for 455 votes. City spokesman Brian Wheeler tells CJR that limiting online responses is “not something these systems do on the back end or that we could enforce on the front end.” As for covering patterns, one such pattern would appear to be an effort to coordinate racist and white-supremacist responses on message boards.

After sending an email and not getting a response, CJR called Daily Progress reporter Tyler Hammel to ask about his coverage of the survey. “Sorry you’re on deadline,” Hammel said, “but your questions are probably directed at the city.” He wished CJR luck, then hung up.

Hammel is right. Questions about the survey’s limits should be directed toward the city. What’s unclear from his reporting, and from the reporting of others, is whether anyone asked them.

ON MONDAY NIGHT, Charlottesville City Council met to discuss the survey results. Mayor Nikuyah Walker voiced her desire to see more community engagement and feedback on the issue. Councilor Heather Hill said some of the survey results were “frustrating, because you know they came from places far away from Charlottesville.” Ultimately, councilors voted unanimously to launch a new survey—narrower in scope, but still including write-in options. The survey will be shared online, and also mailed to many city residents along with their utility bills, and the city expects to complete it by July.

There were plenty of empty seats at the city council meeting this week. Two weeks ago, according to public comments, someone carried a gun into city council chambers during a meeting—something the city council is legally powerless to stop. Footage of that meeting from The Daily Progress does not show a gun, but does show three uniformed city police officers in the chambers. It also shows a white male from Richmond, Virginia, who was previously found guilty of removing a tarp from one of the city’s Confederate statues, using his public comment time to refer to city residents in the room as a “peanut gallery.” Days after that meeting, someone posted a doxing list on Pastebin that included the names of multiple Charlottesville journalists and photojournalists, as well as the names of multiple local residents who spoke to the press.

Yet local residents took up all available public comment slots. They spoke about the city’s ongoing affordable housing crisis, their concerns about over-policing, and the infant and maternal mortality rates in the black community. And, at no small risk to themselves, many gave their full names and addresses.

There’s no shortage of stories to be written about the intersection of Charlottesville’s history and its ongoing needs. Many of those stories will come up against symbols and rhetoric whose influence, in the wake of August 12, reach well beyond the city and into the national consciousness. Plenty of the news outlets mentioned here have made meaningful efforts at telling those stories. But they must stay vigilant for those moments when violent rhetoric finds an open door—in a survey, in a meeting, in a story—and invites itself in.

ICYMI: The outrageous editorial by a Charlottesville daily that preceded violence

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.