Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

The day Roldo Bartimole turned 35—April 5, 1968—a crisis of conscience struck him. Martin Luther King had been assassinated the night before, and riots had broken out in major US cities. Bartimole, a Cleveland journalist who’d gone to the 1963 March on Washington, attended a meeting between George Wiley, a civil-rights activist, and several Ohio college professors. He was appalled when the white professors asked Wiley when riots, not injustice, would end.

“It felt to me like things were as bad as they could be,” Bartimole recalls.

By day, Bartimole worked in The Wall Street Journal’s Cleveland bureau. He moonlighted as an anonymous writer for a Cleveland Council of Churches newsletter. At the nation’s moment of despair, he felt the need to do more.

ICYMI: (MORE) guided journalists during the 1970s media crisis of confidence

So Bartimole actually made the move that countless reporters have fantasized about. He quit his newsroom job and started his own publication, a newsletter he named Point of View.

“I tried to tell the story that I saw as a reporter,” recalls Bartimole, “but knew would never be published in a traditional newspaper. So I had to invent something.” Typed after hours on a church’s IBM Selectric, printed on heavy-stock 11-by-14-inch paper, Point of View became the underground samizdat of Cleveland’s political, business, and journalistic circles.

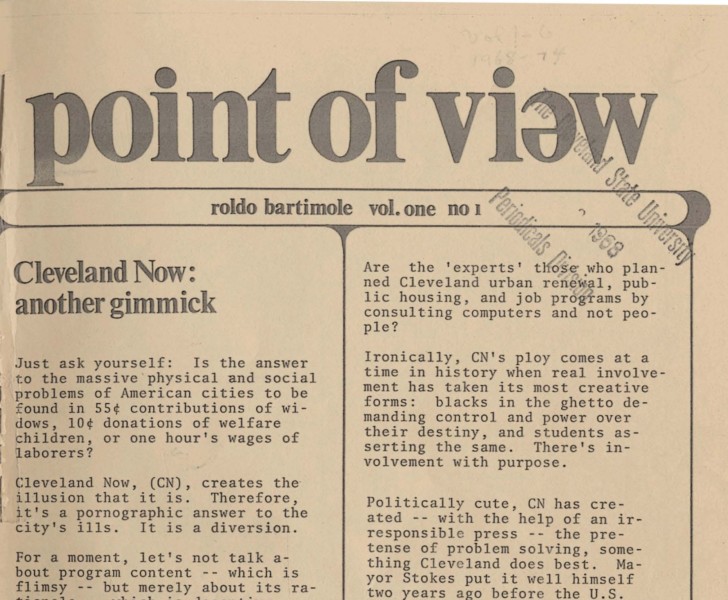

A clip for the first issue. Read the full PDF here.

Bartimole became Cleveland’s first alternative journalist—a role he continued for 50 years, until he called it quits this February, just before he turned 85. For 32 years, Bartimole’s Point of View, funded via subscriptions, combined media criticism with inside information and radical critiques of the local power elite. His solo reporting career inspired comparisons to I.F. Stone’s national weekly of the 1950s and 1960s. After retiring the newsletter in 2000, Bartimole continued as a columnist for the alt-weekly Cleveland Free Times and various local websites—always living on a very low income, the self-imposed price of independence.

“He was a real factor in the town,” says Michael D. Roberts, a longtime Cleveland writer and editor and Bartimole’s contemporary. “His criticisms were embarrassing, to-the-point, and he didn’t spare anyone.”

Like in many cities, Cleveland’s press is much more comfortable critiquing elected power than unelected power. Reading Roldo was the great exception. (Clevelanders always referred to him by his distinctive first name, shared with his father, whom his grandmother named after the hero of a cheap Italian novel.) Bartimole’s work instructed generations of local journalists in how business figures wield power out of sight, leveraging philanthropic dollars, campaign donations, and private meetings with top politicians to control the civic agenda. Though his relationship with mainstream media outlets was unfailingly acerbic, he encouraged young reporters to see the power behind City Hall.

“Don’t compromise,” Bartimole advised his younger readers at the end of his last column. “It’s not worth it and it’s not as much fun or as rewarding at the end. Challenge. Bend as little as possible. Make the bosses bend. They’re not that tough.”

I had a completely different view. My view was that racism and poverty were the cause of what was happening.

BARTIMOLE’S MUCKRACKING BEGAN in his hometown of Bridgeport, Connecticut. His damning reports from the city’s impoverished neighborhoods, which angered the city’s mayor, identified dangerous tenements where children later died in fires. Hired in 1965 by Cleveland’s morning newspaper, The Plain Dealer, Bartimole contributed to a series, “The Changing City,” that was one of the paper’s first frank examinations of urban renewal and what was then known as the black ghetto. His work stood out compared to the paper’s usual attitudes.

“There was a real current of racism,” says Roberts, 79, who was a Plain Dealer reporter in the ’60s. “The black community didn’t exist. You’d call in a story, and the editor would ask, ‘Is it a good address?’” Bad addresses were black neighborhoods, says Roberts, of little news value to the era’s editors.

Point of View debuted in the racial crucible of summer 1968. Many early issues burned with Bartimole’s fury at the city power structure’s treatment of black Clevelanders. After Cleveland’s Glenville shootout between police and black nationalists and the riots that followed—50 years ago this week—Bartimole excoriated police conduct and questioned official accounts of the shootout. “Who polices the police?” he wrote, prefiguring today’s debates about police accountability and use of lethal force. Point of View’s Glenville commentary contrasted with the coverage in Cleveland’s daily press, which generally accepted the police’s version of events.

“I had a completely different view,” recalls Bartimole. “My view was that racism and poverty were the cause of what was happening.”

Point of View’s second issue broke the news that Cleveland businessmen had paid black activists $40,000 to “keep the peace” in summer 1967. “Politics as social control,” Bartimole called it, noting that unrest could’ve scuttled Carl Stokes’s election in November 1967 as the first black mayor of a major US city.

Roberts says Bartimole’s reporting on local power players broke new ground. “He saw the business community sort of as the deep state,” Roberts recalls. Point of View delivered critical coverage of the Cleveland Foundation, the city’s largest philanthropic organization. It scrutinized the political and civic activities of business leaders such as Jack Reavis, managing partner of Jones Day, Cleveland’s largest law firm, and founder of the local Businessmen’s Interracial Committee on Community Affairs. “If you were at The Plain Dealer,” says Roberts, “you didn’t dare go into those waters.”

Bartimole believed business leaders got involved in civic affairs for selfish reasons, not benevolence. “Certain interests were making major decisions, and making them as self-interest,” Bartimole recalls. “Cleveland was a very institutional town, and still is.” Much of Cleveland’s wealth from its boom years in the 1920s is still left in the hands of foundations, Bartimole observes—“structures that keep an agenda going that favors those who have. Not much has changed.”

Point of View was also a journalism review, says Bartimole. His press coverage was inspired by the Chicago Journalism Review, founded by Chicago reporters in response to their editors’ apologias for police violence at the 1968 Democratic convention. Bartimole covered tensions between reporters and management at Cleveland’s dailies, the Plain Dealer and the Press. He printed killed stories and deleted grafs smuggled out of the Plain Dealer newsroom, including an exposé of local nonprofits’ interlocking directorships, deep-sixed by the publisher.

Roberts, the Plain Dealer’s city editor in the early ’70s, says he often thought Bartimole’s criticism of the paper was unfair. Disgruntled Plain Dealer reporters would use him, Roberts says, to get back at management.

But Roberts admired Bartimole’s dogged coverage of Cleveland politics. “He helped spark the way the two papers covered City Hall,” he recalls. “They couldn’t do a slipshod job, because he’d come out with what really took place. The town was lucky to have him.”

In the ’70s and ’80s, Bartimole frequented Cleveland City Hall and the Cuyahoga County Recorder’s office, where he’d find stories in newly-filed partnership records. In January 1982, Point of View reported that the Cleveland Press’s owner had transferred the paper’s land to a new partnership he controlled—a harbinger of the afternoon paper’s shutdown six months later.

Other Point of View stories came from tips on the street. “I walked around downtown a lot,” Bartimole says. “People, if they saw me, would stop and tell me something. They would never call me up to tell me that. But if they met me, they seemed almost obligated to want to tell me something.”

City Hall coverage included epic critiques of Cleveland politicians such as future congressman Dennis Kucinich, mayor from 1977 to 1979, and George Voinovich, mayor in the ’80s and later Ohio governor and a US Senator. Bartimole once confronted Voinovich at a City Hall food drive, grilling him about why he hadn’t opposed President Ronald Reagan’s food-stamp cuts more strenuously.

Bartimole’s most famed confrontation with a politician came in 1981, when George Forbes, Cleveland’s City Council president, forcibly removed him from a meeting. Bartimole felt Forbes was breaking Ohio’s sunshine law, and his refusal to leave more than made his point. “He just got really upset and grabbed me,” Bartimole recalls. “His misfortune was, he had all the media right outside the door, which was open.” Newspaper and TV cameras captured the scuffle. A photo of Forbes grabbing Bartimole by his suit has become one of the legendary images of Cleveland journalism.

George Forbes removes Roldo Bartimole from City Council meeting. Photo courtesy of the Michael Schwartz Library at Cleveland State University.

Though Point of View was widely read in government offices, newsrooms, and corporate boardrooms, widespread photocopying expanded its audience beyond its small circulation: about 500 at the start, peaking near 1,700 in the late ’70s, around 1,400 afterward. Annual subscriptions were $3 in 1968, $25 to $50 in 2000.

Independence meant extreme frugality for Bartimole. “He had virtually no money,” Roberts recalls. “He’d park his car in the cheapest place in town and walk a mile or two miles to get where he was going. I’d always call him a communist when I’d see him. He’d give me the finger.”

Bartimole says his annual income in the 1970s through the 2000s ranged from about $4,000 to $10,000 a year. “It was 32 years with not a lot of money,” Bartimole says. “How could you make any money on that?” For most of the ’70s, he drove a 1965 Volvo, even after it needed a push or a blow from a hammer to start it. At one point, Bartimole raised his three kids, alone, on his writing. He shrugs it off: They had a car, a fridge. “It wasn’t easy. My kids understood it. I think they are proud of it in some ways.” His children would help him stick mailing labels on the newsletters and bundle them for the mail.

Bartimole never considered rejoining a newsroom. “I felt what I was doing was important,” he says. “I could never feel comfortable in a regular job.” He feared compromising his independence. In the 1960s, he’d written a short-lived column for the city’s longtime black newspaper, the Call and Post, in exchange for the paper printing Point of View for free. But when the publisher refused to run a Bartimole piece critical of the local United Way, he walked.

At one point a Cleveland Press editor asked Bartimole to write a column. “I refused, because I knew what was going to happen,” he says. “I’d write one they didn’t want to run, and then I’d be out.”

I knew I couldn’t play a different role, clean things up, and go back on what I was writing.

IN THE 1980S AND 1990S, Bartimole started making more money by becoming a columnist for local alt-weeklies, first the Cleveland Edition and later the Cleveland Free Times. He continued Point of View, splitting his writing energies. It’s the only time he made a living wage, he says. “I was hurting myself, cutting into subscriptions,” he says. “But I got paid, and it was way more exposure.”

Bartimole became a sort of frugal populist, Cleveland’s fiercest critic of tax abatements for downtown development projects and public funding for stadiums. He opposed the 1990 ballot campaign to levy alcohol and cigarette taxes to fund the Indians’ baseball stadium, now Progressive Field, and the Cavaliers’ basketball arena, now Quicken Loans Arena. He printed lapel pins and bumper stickers calling out then–Indians owner Dick Jacobs: “Let Jacobs Pay,” they read.

At age 67, Bartimole began a long, slow retirement. He shuttered Point of View in 2000, but continued writing his column for the Free Times until it closed for seven months in October 2002. By the time the paper was revived as part of an antitrust settlement in May 2003, Bartimole had already moved his column to a black newspaper, the City News and Tab, where he wrote into the mid-2000s.

Even semi-retired, writing without pay for local websites such as Cool Cleveland, RealNEO, and Have Coffee Will Write, Bartimole decried the more than $1 billion in local tax money that’s gone to build and renovate Cleveland’s sports palaces. Sometimes it seemed like he was the only journalist in town who could explain how the complex funding worked.

A 2009 account of Bartimole’s walk through downtown Cleveland, unusually narrative for a writer who focused on facts and figures, catalogued the deals that had subsidized each new building. His tally ran to $660 million—with, he felt, not enough people on the streets to justify it. “Activity will come when people—the market—demand it,” he wrote. “You can’t force it even with almost free money.” That was heresy in Cleveland, which prides itself on its downtown’s subsidized comeback.

“There was no down-the-middle in how people viewed him,” recalls Roberts. “You either liked him for what he was doing, or thought he was a crackpot.”

Despite Bartimole’s career of castigating the city’s daily paper, Roberts lobbied his fellow Press Club of Cleveland members to induct Bartimole into their Hall of Fame in 2004. They agreed, reluctantly. Among other journalists, “he was not well-liked, generally speaking,” Roberts recalls. “He had a group of guys who were his friends, but the editors detested him. They asked, ‘Why take this guy in who’s been spending his career criticizing us?’”

Bartimole’s acceptance speech made Roberts cringe.

“I knew I couldn’t play a different role, clean things up, and go back on what I was writing,” Bartimole recalls, “so I slashed out at The Plain Dealer.” The outsider journalist dismissed local TV news as “essentially hopeless and headed south,” radio as “mostly irrelevant,” and The Plain Dealer as “too often put[ting] its readers and reporters to sleep” and spending more effort on food and sports coverage than “its coverage of who is doing what to whom.”

To Roberts and others in the audience, Bartimole’s speech was memorably mean-spirited. “He enjoyed that,” Roberts says. “He’s got an ego. That was one of the things that drove him.”

WHAT LEGACY IS BARTIMOLE LEAVING, in Cleveland or beyond? His own answer is modest. “One person doesn’t make that much of a difference,” he says. “It takes movements.”

But Sam Allard, a staff writer for the alt-weekly Cleveland Scene, disagrees. Allard, 30, wrote about Bartimole’s influence on Cleveland journalism for Scene this winter. “He took a real interest in mentoring and fostering younger journalists in Cleveland, myself included,” says Allard. “He was actively calling, emailing and setting up coffee dates.” Allard says Bartimole advised him on his 2017 coverage of an issue dear to the elder journalist: an activist group’s aborted battle against new public funding for Quicken Loans Arena. “One of the things he saw his role as was helping shape media discourse in town. He thinks it’s important to reach out to people who are crafting the narrative.”

In local journalism, calling out unelected power can make reporters uncomfortable and power brokers hostile. “One of the things that’s inspired me the most about Roldo,” says Allard, “is that he spent his entire career writing and reporting critically about people he interacted with regularly. It’s a lot more courageous to report critically about people in your town or community.”

Bartimole’s advice for young journalists trying to cover power in their city is simple. “Look at records, and look at who benefits and who pays,” he says. “Pick out, what are the institutions making decisions? How do certain things get before the public officials to ratify? Look at the organizations that are considered quote-unquote ‘good.’ What are they doing with their money? How are they collecting it?”

Unelected power brokers “come out when there’s certain crises and things have to be quote-unquote ‘handled,’” Bartimole says. “If you watch, you can see that happen. Who pulls certain strings at certain times?”

ICYMI: How a star freelancer found her way from Marfa, Texas, to The New Yorker

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.