Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

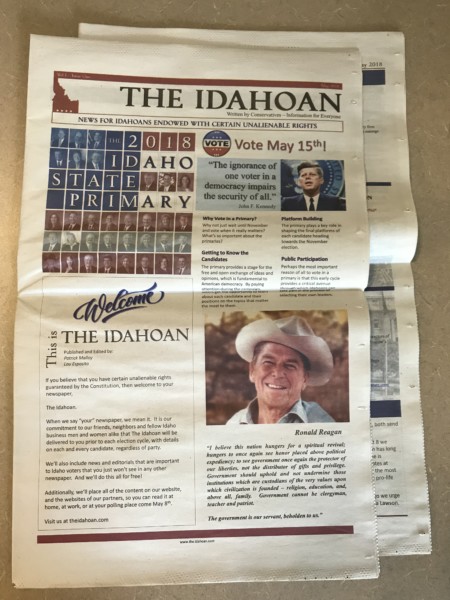

THE IDAHOAN IS A NEWSPAPER; at least, that’s what its publisher says. As of this week, the Idaho Attorney General’s office agrees with him. But journalists in the state, as well as the local Democratic Party, see it differently. They say the 48-page, two-section publication—which was printed on newsprint and dropped through the mailboxes of voters statewide early this month—is scarcely concealed campaigning material, designed to drum up support for conservative Republican candidates ahead of closely contested elections like this week’s primaries.

In The Idahoan’s inaugural editorial, longtime political operatives Lou Esposito and Patrick Malloy laid out plans to run editions in advance of future local election cycles, as well as the opening of state legislative sessions. Although Esposito says he wants to print more regularly in the future, this schedule struck many observers as suspicious. On May 4, Idaho Democrats cried foul, asking the state government to investigate whether the publication is attempting to circumvent campaign disclosure laws by disguising a political mailer as a newspaper.

On Monday, Deputy Attorney General Brian Kane ruled that while The Idahoan bears striking similarities to campaign literature, it qualifies as a newspaper under an exemption in Idaho’s Sunshine Law, which stipulates that newspapers needn’t disclose their funding as long as they aren’t controlled by a party or candidate. He added that The Idahoan may not qualify for an exemption under broader, federal campaign laws because “it appears that The Idahoan is controlled by political committees.” But as Idaho’s newspaper exemption doesn’t take PAC control into account, The Idahoan—for the time being, at least—is under no obligation to disclose its funders.

ICYMI: Veteran editor announces on Twitter he was fired from newspaper

Esposito is a veteran Idaho PAC player, and many of The Idahoan’s advertisers are PACs. He denies that he controls any of the PAC money coming into the publication’s coffers. Nonetheless, its appearance on the scene, and the state’s subsequent “newspaper” ruling, has riled up many local journalists and commentators.

The Idahoan invites comparisons to a national wave of pop-up publications which look and feel like traditional news, but are, in fact, run by political operatives or hardline ideologues seeking to give chosen candidates a boost

Lewiston Tribune writer Marty Trillhaase called The Idahoan a “dark money ‘newspaper’” and an “end-run” around the Sunshine Law in a column published last week. In an interview with CJR, Anne Helen Petersen, BuzzFeed’s Western correspondent, adds that “just because it’s printed on newsprint does not make it a newspaper.” And Betsy Russell, Boise bureau chief for the Idaho Press-Tribune and president of the Idaho Press Club, says the publication “points to a need for Idaho to tighten its campaign finance reporting laws, to close loopholes like this one, or our citizens will get oddball stuff like this going out before elections and evading reporting requirements.”

The Idahoan invites comparisons to a national wave of pop-up publications which look and feel like traditional news, but are, in fact, run by political operatives or hardline ideologues seeking to give chosen candidates a boost. Last September, the AP outed the Republican Governors Association as clandestine funders of The Free Telegraph, while earlier this year, Politico reported on a mysterious endorsement for Arizona GOP Senate candidate Kelli Ward in the Arizona Monitor—a website of still-unknown origin which featured little else besides its Ward endorsement, and which shut down after Politico published its report. While Ward’s campaign denied setting up the Monitor, the story’s coauthor, Shawn Musgrave, says it “used [the site’s endorsement], on the level of other publications that covered her,” and that “it was very easy, especially if you’re not digging around the site, to consider the site to be like any other. It had the feeling of a small-town…news website.”

ICYMI: Headlines editors probably wish they could take back

More recently, Politico’s Jason Schwartz reported on the emergence of yet more opaque right-wing outlets across the country, dubbing them “baby Breitbarts.” In a phone interview with CJR, Esposito says he doesn’t recall hearing about this wave of sites, and that the idea to launch a publication like The Idahoan was first bandied around among his associates several years ago. (The name was registered by Wayne Hoffman, currently the head of the influential Idaho Freedom Foundation, in 2007, with ownership switching to Malloy in April. Hoffman did not respond to an inquiry from CJR.)

Esposito says The Idahoan has been transparent, marking clearly on the masthead that it has a conservative bent, and prominently listing him and Malloy as its publishers. “The long and the short of it is there’s really no place for conservatives in Idaho to get information on issues, and/or candidates, and so we felt it was time to correct that,” he says. “There’s nothing nefarious about it. There was a major gap in information and we endeavored to fill that.”

Local reporters like Russell say conservatives do get plenty of coverage in state media. That said, The Idahoan is undoubtedly more upfront about its leanings than many of the publications identified by Politico. It contains straight-up information on candidates from both parties—as well as on how to vote—and Esposito says he intends to open up advertising to candidates—including Democrats—in future editions. Meanwhile, current advertisers and partners—which include PACs with pro-gun, pro-market, and pro-life positions—are clearly marked. Indeed, Esposito says he wants to give these advertisers increased exposure.

Still, The Idahoan has not been fully forthcoming about who is paying for it. While compulsory PAC filings released last week named two local businessmen who part-funded it, much of the rest of the cost was stumped up by investors who remain anonymous. And given that The Idahoan delivered print copies statewide, that cost was likely substantial.

I was just in Idaho this past weekend, and my mom saved all the political mailings that arrive, just so I can see the array that land in her mailbox. The Idahoan is just a slightly less glossy version of the other stuff.

Esposito says it’s hypocritical for others in the media to say he should name his backers. “We are a private enterprise, so we don’t feel any obligation to disclose our business or business practices any more than any other business,” he says. “If people have a problem with us then I guess it’s time for The New York Times, and The Washington Post, and the Idaho Statesman, and the Idaho Press-Tribune to start fully releasing all of their financial information.” Esposito feels his publication is being singled out because critics don’t like the speech it contains. “People know the intent, they know, when this hits their mailbox, they’re gonna get conservative information, conservative endorsements, conservative viewpoints. If they don’t like it they can decide to shred it, or throw it in recycling, or do whatever they want to do with it. That’s their right.”

But many mainstream publications do disclose where their money comes from. And as critics of The Idahoan point out, most newspapers don’t exist to boost specific candidates and issues at election time.

The effectiveness of the publication is uncertain. “I was just in Idaho this past weekend, and my mom saved all the political mailings that arrive, just so I can see the array that land in her mailbox,” says Petersen. “The Idahoan is just a slightly less glossy version of the other stuff that has been coming.” Russell adds that its print edition was riddled with typos and other errors, inviting the scorn of some locals.

https://twitter.com/colinmnash/status/992269763152826368

Tuesday’s primaries were at best a mixed bag for the candidates endorsed by The Idahoan—its pick for a House seat, Russ Fulcher, won his race, but firebrand gubernatorial candidate Raul Labrador lost out to relative moderate Brad Little, and further down the ballot, conservative state legislators and candidates suffered setbacks. “If it was [an ad masquerading as a paper], it was a huge financial investment in a campaign tactic that isn’t typically effective,” writes Justin Vaughn, a professor at Boise State University, in an email. “So whether it was legal or ethical is one thing, but whether it was strategically sound seems unlikely, particularly in light of the underperformance of the ultra-conservative wing in last night’s primary.”

With many midterm races set to be tight, however, it seems likely that at least one of the growing number of conservative news sources might have an impact somewhere in the US. As Politico reported, a site called the Maine Examiner, which appeared to have ties to the Maine GOP, levied potent attacks against a Democratic candidate for mayor of Lewiston ahead of an election which he lost by just 145 votes in December. These partisan publications are, of course, allowed to operate and brand themselves as they wish, within the boundaries of campaign laws. But even where they’re judged to have satisfied those rules, the directly political nature of their work means they should offer up full transparency, articulating not just their worldview and top staff, but where their money has come from.

“Anyone can send out anything they want. We have freedom of speech in this country,” says Russell. “But the Sunshine Law ensures transparency, so that when electioneering communications are going out, the people who receive them also know who they’re getting them from, who’s paying for them, who’s behind this, so that they can make their own decisions about the credibility of those publications.”

ICYMI: ‘Fake news’ seized an Idaho city. A local paper ‘jumped right into the coverage.’

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.