Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

At the recent annual data journalism conference in Denver, Colo., the job postings covered a large bulletin board. News organizations from the Atlanta Journal Constitution to Vox were seeking reporters, editors, producers, designers, and developers.

The catch: Nearly every job asked for expertise in working with data.

For recent journalism school graduates, that requirement may mean a harder time finding a job. Many journalism programs don’t teach even the basics of data journalism.

A year ago, we embarked on a project funded by the Knight Foundation to better understand the state of data journalism education. The results of this study were published in March as a free report titled, “Teaching Data and Computational Journalism.”

Through our research, we interviewed more than 50 teachers and practitioners of data journalism, along with 10 students at both the undergraduate and graduate levels. We also collected information on 113 programs located within the United States that are accredited by The Accrediting Council on Education in Journalism and Mass Communications. That represents about a quarter of the journalism programs in the United States. Of course, It’s possible there are differences in what is taught in programs that are not accredited by ACEJMC. However, ACEJMC states in its accrediting standards that journalism programs will “apply basic numerical and statistical concepts” and “apply current tools and technologies appropriate for the communications professions in which they work, and to understand the digital world.”

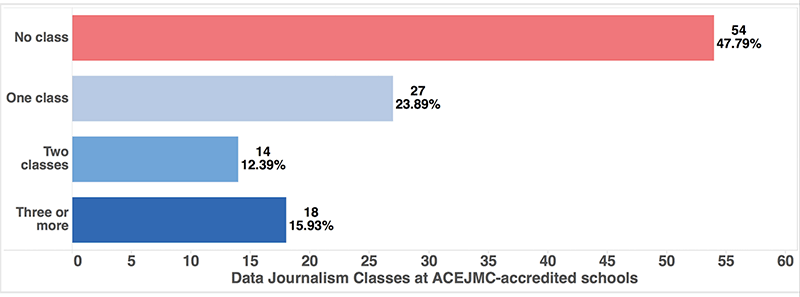

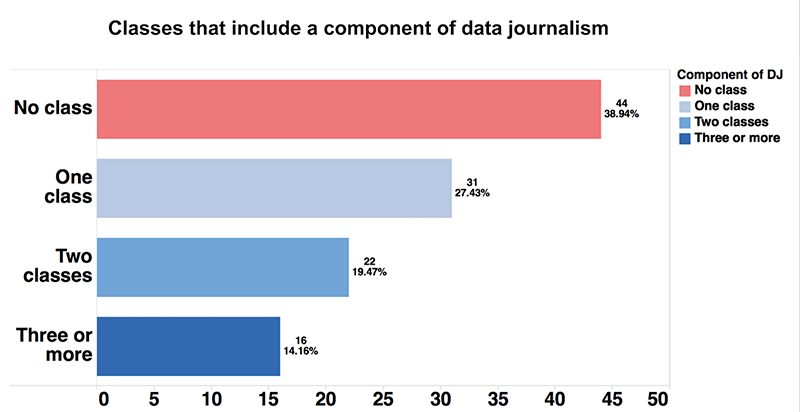

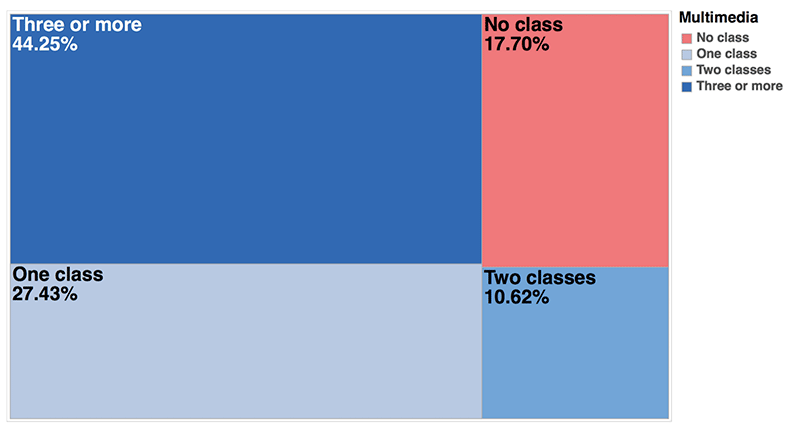

A little more than half, 59 of the 113 schools we reviewed, regularly offer one or more data journalism course. The 59 programs we identified as offering data journalism included a wide range of courses. At minimum, these courses taught students to use spreadsheets to analyze data for journalistic purposes. At the other end of the spectrum, some schools provided far more, teaching multiple classes in programming skills, such as scraping the Web, building news apps, or creating advanced data visualizations.

But those more advanced programs were rare. Of the 59 programs we identified that teach at least one data journalism class, 27 of the schools offered just one course, usually at the introductory level. Fourteen journalism programs offered two classes. Just 18 ACEJMC-accredited journalism schools offered three or more classes in data and computational skills geared toward journalism.

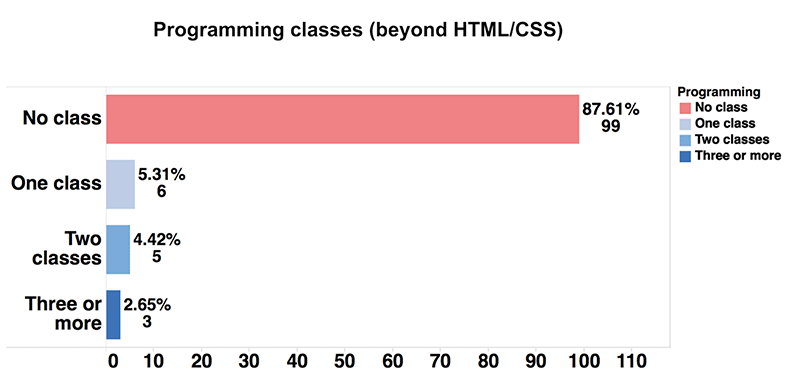

For advanced positions in data journalism–jobs that deal with statistics and mapping, novel forms of data visualization, rich online databases, and machine learning–little is available in the way of data journalism education preparation. Students who study both computer science and data journalism are well-positioned to move into some of these more challenging jobs, but there is a dearth of such job candidates–say, data journalists.

Journalism programs need to do a better job of persuading or requiring students to take a data journalism class. Students may shy away from this type of learning because they believe they aren’t any good at math. One journalism student at Northwestern University told us: “A lot of students are scared of ‘that math thing.’ ”

But the problem is more than math aversion. Even in schools with entire programs focused on teaching programming, data journalism, or data visualization, some students have reported that it wasn’t easy to find out about these opportunities. Sometimes data and computation programs are siloed as concentrations or tracks for certain students rather than treated as skills that could aid in every area of reporting.

The good news is there appears to be strong interest in making changes to journalism education. In the course of checking the curricula offered, at least 11 universities reported they are either considering or already planning to add coursework that covers data journalism.

Dustin Harp at the University of Texas, Arlington, is an example of this increased interest in developing data journalism instruction. Harp is a tenured professor, and no one asked her to take on the extra work to create a data journalism class. “But I follow the field,” Harp says. “I’m aware that data journalism is a tool our students need to be more competitive to get jobs.”

Although it may be difficult to find instructors, we recommend in our report that every journalism program teach at least one required foundational data journalism class. We also suggest ways of integrating data and computational instruction into core classes and electives. For programs that can support it, the report also includes several full-model curricula, including a model for a research-driven, lab-based graduate degree in emerging media and technological innovation.

The goal throughout our research has been to help journalism education move toward a more cohesive and thoughtful vision, one that will help educate journalists who understand and use data as a matter of course—and as a result, produce journalism that may have more authority, yield stories that may not have been told before, and develop new forms of storytelling.

Steve Coll, the dean of the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism, describes the emergence of instruction in data-driven reporting practices as a recognition that data journalism is about more than just publishing stories through digital media, but is also about developing reporting methods appropriate to the complexity of the world today.

“It [data journalism] looks powerful because, in comparison to the way journalism schools have responded to previous iterations of technological change, this one runs deep, and to the heart of professional practice. It’s not about shifting distribution channels, or shifting structures of audience,” Coll says. “It was very tempting, in many ways necessary, for journalism schools to rush over to the teaching of tools, the teaching of platforms, the teaching of changing audience structure. But that transformation often had little to do with the core, enduring purpose of journalism, which is to discover, illuminate, hold power to account, explain, illustrate.”

Delving into data journalism brings journalism back to its journalistic mission and moves it ahead in its research mission at the same time, Coll says.

“What we’re really seeing now is that this is a durable change in the structure of information, and therefore a need to durably change a journalist’s knowledge in order to carry out their core democratic function. Not to build a business model, not to reach more people, not to have more followers, but to actually discover the truth—you need to learn this.”

The report can be read online or downloaded as a PDF.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.