Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

In the span of two years, mounting civil unrest concerning unequal treatment of minorities led to large protests in three cities that generated national media coverage. It wasn’t Ferguson, New York City, and Baltimore—it was Los Angeles, Chicago, and Newark in the mid-1960s. In 1967, Lyndon B. Johnson appointed the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders to answer three questions about these protests: What happened? Why did it happen? What can be done to prevent it from happening again?

While the Commission called for an increased emphasis on better housing, education, and social service policies, some of its strongest criticism was directed toward mainstream media. “The media report and write from the standpoint of a white man’s world,” they wrote in 1968. “Fewer than 5 percent of the people employed by the news business in editorial jobs in the United States today are Negroes.”

How much have things improved? According to the 2014 American Society of News Editors (ASNE) census, the number of black newsroom employees has increased from “fewer than 5 percent” to … 4.78 percent.

As a PhD student at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania, I study trends in journalism. I wanted to find out why this number hadn’t improved in nearly five decades, so I started digging. What I found was unsettling. (It is worth noting that the two surveys–one calculated by the government and the other by a nonprofit many years later–cannot be directly compared. That they arrived at similar numbers, though, shows that the situation hasn’t much improved.)

First, there is some good news. The percentage of minorities employed in daily newspapers (the ASNE looks at black, Hispanic, Asian American, Native American, and multiracial populations) has increased from 3.95 percent in 1978, when the ASNE began conducting the census, to 13.34 percent in 2014. The Radio Television Digital News Association estimates that in 2014, minorities made up 13 percent of journalists in radio and 22.4 percent of journalists in television.

Still, these figures are a far cry from the 37.4 percent of Americans that are minorities. As the Commission pointed out nearly 50 years ago, unequal employment may lead to unequal coverage, a complaint that persists today. It may also simply be bad business, given the “staggering” purchasing power of minorities, the opportunity to attract more readers, and research that suggests minorities may be more interested in local news than caucasians.

So why aren’t there more minority journalists?

When BuzzFeed asked Ben Williams, digital editorial director of NYMag.com, what would make it easier for him to hire more diverse candidates, he expressed a common sentiment–that there are not enough candidates. “It’s well-established that, in part due to economic reasons, not enough ‘diverse’ candidates enter journalism on the ground floor to begin with,” he’s quoted as saying. “So the biggest factor in improving newsroom diversity is getting more non-white … employees into the profession to begin with.”

To find out if this reasoning is accurate, and, if so, what’s causing it, I looked at data from newsrooms and universities. Specifically, I examined how many minorities majored in journalism in college, how many minorities graduate from such programs, and the job placement rate of minorities when they graduate. Here’s what I found:

Are minority students majoring in journalism?

Grady College’s Annual Survey of Journalism & Mass Communication Enrollments collects surveys from at least 458 universities about their college majors. Between 2000 and 2009, minorities accounted for approximately 24.2 percent of journalism or communications majors. While this number is not high, it’s still not as low as the number of minority journalists working in newsrooms today.

Are minority students graduating from journalism programs?

Using Grady College’s Annual Graduate Surveys, I then examined the demographics of bachelor’s degree recipients. Between 2004 and 2013, minorities accounted for approximately 21.4 percent of journalism or communications graduates. Again, while it is not a high number, it doesn’t explain the low number of minority journalists.

Are minority graduates of journalism programs finding jobs?

Using unpublished data from Grady College’s 2013 Graduate Survey, I analyzed how many minority bachelor’s degree recipients from 82 colleges earned full-time jobs within 6 to 12 months after graduating with a journalism or communications degree.

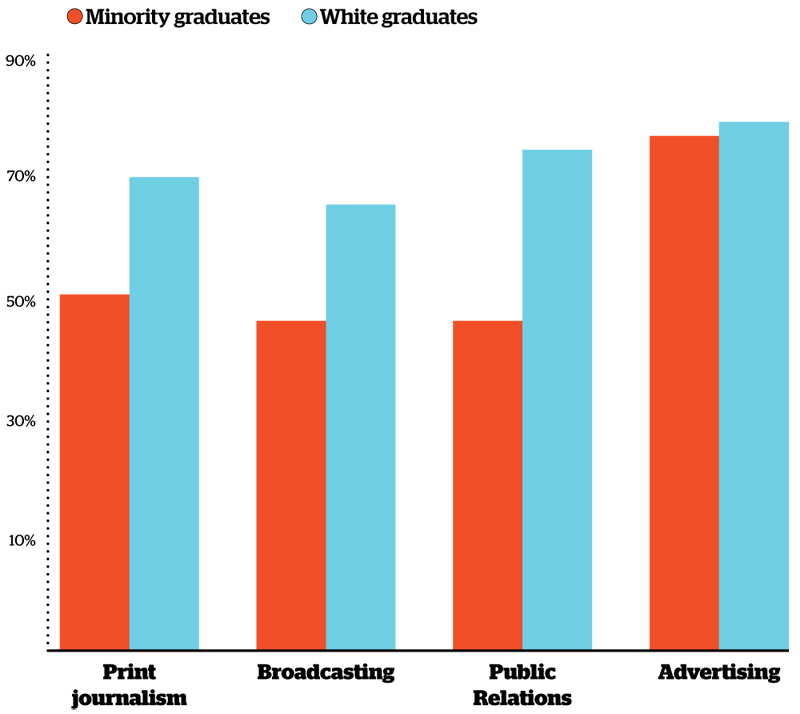

Here, I found an alarming trend. Comparing the 2013 job placement rates, graduating minorities that specialized in print were 17 percentage points less likely to find a full-time job than non-minorities; minorities specializing in broadcasting were 17 percentage points less likely to find a full-time job; and minorities specializing in public relations were 25 percentage points less likely to find a full-time job. In contrast, minorities specializing in advertising were only 2 percentage points less likely to find a full-time job than their white counterparts.*

Overall, only 49 percent of minority graduates that specialized in print or broadcasting found a full-time job, compared to 66 percent of white graduates. These staggering job placement figures help explain the low number of minority journalists.

The number of minorities graduating from journalism programs and applying for jobs doesn’t seem to be the problem after all. The problem is that these candidates are not being hired.

There are likely three key factors that help explain this hiring discrepancy:

- First, Nieman Reports has noted that minority students are less likely to serve on campus newspapers because they are more likely to attend colleges without the resources to support a newspaper or to feel ostracized by a mostly white newsroom.

- Second, minority students are less likely to complete unpaid internships. As The Atlantic wrote in 2013: “Unpaid internships compound diversity concerns by reserving entry-level journalism positions to financially advantaged youth who can afford to work for free.”

- Lastly, minority students often aren’t in the hiring networks that editors rely on to find job candidates. Shani O. Hilton, executive editor at BuzzFeed, wrote on Medium that she believes minority journalists are so busy working twice as hard for half of the credit that they overlook the importance of networking.

But are minority students that graduate with a journalism degree unqualified to be journalists because they didn’t volunteer on the campus newspaper or complete an internship?

With the economic crisis facing journalism, it’s not surprising that publishers want to hire graduates who can hit the ground running–those who have more experience or come personally recommended. This means that we need to do a better job of attracting minority high school and college students to participate in school newsrooms and create more diversity scholarships and paid internships. But we also need to scrutinize the hiring bias that hurts the job prospects of minorities graduating with journalism degrees.

When newsrooms eliminate candidates because they didn’t volunteer on the campus newspaper, complete an unpaid internship, and come recommended by a friend–it disproportionately affects minority candidates. This has led to the myth that minorities are not trying to enter the field of journalism. They are. They’re just invisible because they aren’t getting job interviews.

Rather than approaching hiring with a one-size-fits-all mentality, newsrooms should try to interview a variety of candidates. If a job candidate is a solid, curious writer with drive and a good work ethic, they deserve consideration. By making this small adjustment, more minority candidates will get their foot in the door–literally–which could help address the decades-long criticism that newsrooms need more diversity.

*Clarification: It was not originally clear that the reported percent comparisons calculated the difference in raw percentage points and not the relative difference between percentages. It has now been updated to clearly state that percentage points are being used.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.