When Jim Morris told CJR about the Center for Public Integrity’s labor and environment team in March, he extolled the virtues of putting both topics under one umbrella. “We’re talking about things like toxic chemicals in the workplace,” he said. “It’s heavy on science…We’re going to stick with workplace health and safety reporting, because it’s incredibly important.”

That philosophy, which led to a 2014 Pulitzer Prize for a series on coal miners’ fight to claim health benefits, continued bearing fruit this week. On Monday, CPI began publishing findings of an 18-month investigation on work-related disease in America. The multi-part exposé, complete with methodology, catalogues the toxic substances that many Americans come into contact with in the workplace—and the weak federal regulations that fail to police them. Workers from construction sites to grocery stores to semiconductor manufacturing plants often touch or inhale chemicals that hold the potential, advocates say, to irreparably damage or end lives.

The conclusions are jarring in and of themselves. But what makes them even more frightening is the knowledge that such conditions exist—indeed, they’re often legal—in one of the most advanced countries in the world.

CPI and several other news organizations have renewed their focus on workplace issues in recent years, an about-face after the decades-long decline of the more-traditional, union-focused “labor” beat. The reversal came in wake of the financial crisis, when stagnant wages and income inequality took center stage in the American political arena. Much of the coverage, from mainstream media to left-wing outlets, centers on such economic concerns. But CPI has focused its efforts on a different—though no less important—aspect of labor coverage. It targets the intersection of workers’ rights and public health, and it consistently connects in a big way.

CPI’s lead piece on Monday outlined how a shoddy federal regulatory regime allows various toxic substances to pollute American workplaces, despite far stricter guidelines for protecting the general public from chemical exposure. Inhaled or otherwise touched by workers, these substances lead to an estimated 50,000 deaths, hundreds of thousands of illnesses, and tens of billions of dollars in medical expenses and lost productivity each year—what the piece’s headline terms a “slow-motion tragedy for American workers.”

The blight of disease contracted on the job isn’t confined to factory workers. It consumes hairdressers, grocery store meat-wrappers, scientists and people in a variety of other professions. Many are stricken by middle age.

The panoply of illnesses, from nerve damage to dementia to virulent cancers, takes a profound toll on workers and their families. Careers are lost, finances shredded, marriages tested. In some cases, workers opt for macabre, last-ditch procedures to try to save their lives…

Federal regulators are overwhelmed by the scope of the problem, which didn’t materialize by chance. Congress has exacerbated the situation by refusing to fortify the weak 1970 law specifying what [the Occupational Safety and Health Administration] can do. Trade groups have challenged health standards in court while workers lose their lives. The White House’s Office of Management and Budget is a vortex that sucks in proposed agency rules and doesn’t spit them out for months — or years.

The potential injustice isn’t merely that workers toil amid substances known for their toxicity: lead, silica, and hexavalent chromium, to name a few. It’s that such conditions are typically legal. Efforts to tighten such regulations have been hamstrung by Congress or the White House, CPI reported in an analytical sidebar Monday, and public agencies tasked with enforcing them lack the resources to do so effectively. The current head of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, meanwhile, freely acknowledged to CPI that the body’s rules are “weak and out of date, or simply non-existent.”

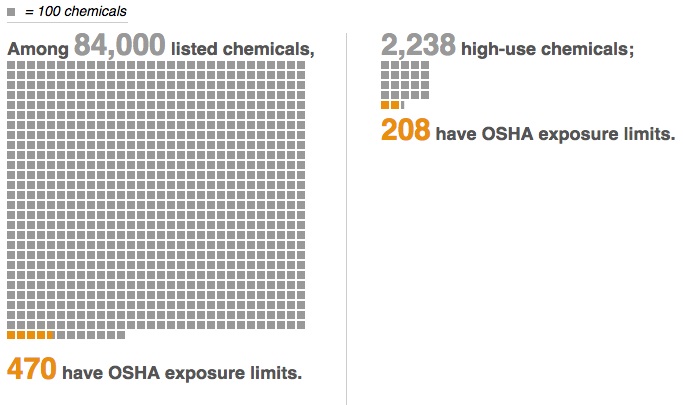

(The Center for Public Integrity)

Though industry groups aren’t uniformly opposed to additional protections, they generally argue that the threats of workplace toxins are overstated. What’s more, they boast large war chests with which to lobby lawmakers, challenge rules in court, and finance research that casts doubt on regulators or independent investigators. It’s important to note, however, that in most cases businesses are indeed following the rules, as the vast majority of tens of thousands of chemicals used in workplaces fall under no rules at all.

Perhaps the most powerful of CPI’s stories published this week—a third round will run on July 6—was Morris’ explanatory feature on the way toxins can affect workers’ children in utero. He tells the story of Yvette Flores, whose employment at a laser production facility exposed her to lead and methanol while she was pregnant. Flores’ son, Mark, was born with a range of severe birth defects: “His eyes were crossed. His testicles had failed to descend. His hips were dislocated. He was unable to suck on a breast or bottle. His head was covered with large blood blisters, known as hematomas.” Now 35, Mark Flores lives with his mother and speaks mostly in monosyllables, Morris writes. When Yvette Flores brought a lawsuit against her former employer, it argued that Mark’s disabilities stemmed from a genetic condition. The case was settled out of court in 2013.

What’s heartwarming about the story is Yvette’s unquestionable love for her son, despite myriad day-to-day challenges. “Mama takes care of you,” Morris quotes her as telling Mark. “It’s you and me, right?” What’s heartwrenching is that the conditions that potentially led to his health problems persist, and little is being done to change that. CPI deserves praise for spotlighting the dangers when many have looked away.

David Uberti is a writer in New York. He was previously a media reporter for Gizmodo Media Group and a staff writer for CJR. Follow him on Twitter @DavidUberti.