Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

This week, after years of negotiating and planning, five of the largest Internet service providers in the country, in partnership with movie and music trade groups, have started implementing a new “copyright alert system.” The system–a form of internal policing, with ISPs cast as enforcers–zeroes in on Internet users who are downloading copyrighted content, chastises them, and, if that doesn’t work, punishes them for their defiance.

Customers of Cablevision, AT&T, and Time Warner might not have heard about this yet–but they will soon. Verizon and Comcast have already begun notifying their users about the program, and Comcast confirmed to CJR that on Wednesday it started sending out “a small number” of alerts of alleged copyright infringement.

The private sector came up with this program as an anti-piracy strategy that could be implemented without any help from the government. ISPs aren’t exactly fond of peer-to-peer sharing: it takes up a huge amount of bandwidth. And trade groups are convinced that they can use it change consumer behavior.

So if you’re sloppy about downloading music or movies from a peer-to-peer network, like BitTorrent, μTorrent, Vuze or Frostwire–if you don’t mask your IP address with a VPN or similar shield–you might start hearing about it.

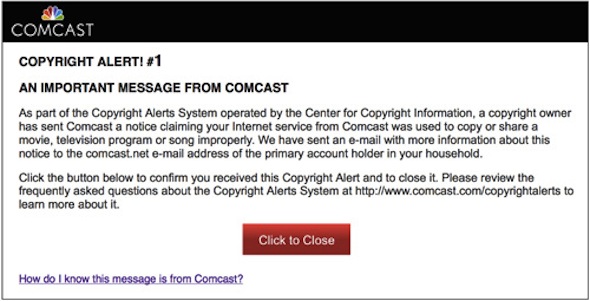

The alerts start with a message that a copyright owner (likely one represented by the Motion Picture Association of America or the Recording industry Association of America) has connected allegedly improper sharing or copying of content to your IP address. If you’re a Comcast customer, for instance, your first alert will look like this:

Notices like this one aren’t actually new; some ISPs have been sending similar alerts to customers for years. What’s different about the copyright alert program is what happens if copyright holders keep tracking downloads to a particular IP address.

This part of the program works like the penalty system in a soccer game: With each infraction, the warning gets more serious. At worst, bad behavior will get you suspended from playing the game for a little bit–as part of the fifth and sixth “alerts,” Internet service is slowed down to a crawl or the customers’ ability to browse the Web is blocked by a notice that only the ISP can disable. But you can’t be kicked out of the league. Participating ISPs say–for now–that they’ll never cut their customers off from the Internet permanently for copyright infringement.

Six strikes and you’re…

Here’s what happens before a customer receives that first alert. The participating copyright owners (they include Disney, Paramount, Sony, Fox, Warner Bros., and EMI) put together lists of content they want monitored. Those lists go to an outside group–MarkMonitor–which joins and monitors peer-to-peer networks in order to hunt down people sharing that content. There’s not a lot of public information available about this process: The Center for Copyright Information, which is overseeing the whole copyright alert program, last year are worried that this system will start closing down the open Wifi movement and will stop the culture of coffee shops and other public spaces offering free Internet.)

It’s also possible to defend your actions on fair use grounds, but the Center for Copyright Information’s website makes this sound tricky–it advises enlisting a lawyer before even trying. But you likely have a better chance of winning on this defense than on “misidentification of account” and “misidentification of file.” When presented with either of those two defenses, it’s up to the challenger to prove that the automated systems didn’t work in accordance with their specifications–a hard case to make, given how little information there is about them.

But will it work?

In this presentation, for instance, the RIAA’s deputy general counsel lays out the case for the copyright alert system. She cites a study of digital music that found that almost two-thirds of music changes hands without anyone paying, through digital lockers, hard drives, burned and ripped CDs, or peer-to-peer networks. In 2010 and 2011, according to the study, peer-to-peer transfers actually were less of a problem than people trading hard drives or ripping music. But the presentation argues that, in countries like France and New Zealand, programs like the copyright alert system have both cut into illegal peer-to-peer downloading and increased sales.

That may be an optimistic view of how well these programs have worked. In France, only a handful of people have received three strikes–the maximum number of warnings in that system–and last year the government cut funding for the program by a quarter. According to a French government report, fewer people were illegally downloading content, and more said that they were likely to download music and movies from legitimate sources. But there are also some indication that, contrary to what they tell the government, people in France are simply switching from peer-to-peer networks to streaming or digital lockers in order to access music and movies.

No one involved thinks that these alerts will stop determined downloaders. It’s simple enough to shield an IP address that anyone who wants to keep snagging movies or music from networks like BitTorrent should be able to figure out how, well before their ISP gets around to sending a fifth of sixth warning.

Disclosure: CJR has received funding from the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) to cover intellectual-property issues, but the organization has no influence on the content.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.