Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

A year after he died suddenly in the newsroom of The New York Times, David Carr still pops up several times a day on the Google Alert I set for him back in 2005, when he first explained to me what that was. This is not ironic, rather simply true in the way that something you learn from someone keeps them in your mind.

No one made the transition—the “migration,” as he was one of the first to call it—from legacy to digital better, although David always said that Brian Stelter, a colleague of his then at the Times, was the new prototype for a journalist. He pointed to Stelter’s growing presence on various platforms, especially Twitter, and his early citing of a student who’d remarked, “If the news is that important, it will find me.” David said that was all you needed to know about where news was going. But David was the one everyone I knew started following, as he became ubiquitous himself in the evolving news ecosystem he helped define. He mastered and interpreted the new tech—speaking Twitter like the native he was—and still delivered reported, stylish print columns for the paper every Monday.

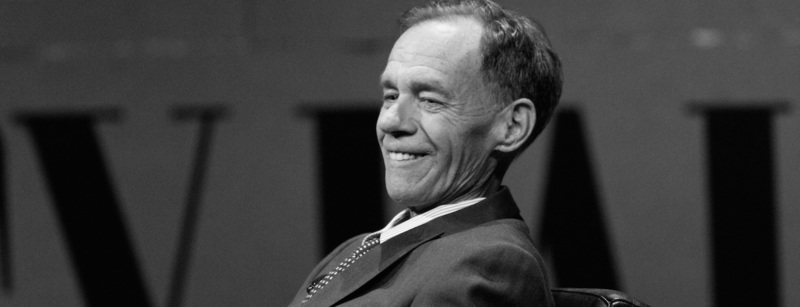

He was gifted and haunted, and you saw that right off. He had been handsome as a kid but by his early 40s, when we met, he looked like a cousin of the Edgar the Bug character from Men in Black, with a ropy neck and tortuous posture and clothes that never quite fit because of his fluctuating weight. I first became aware of him through his work at Inside.com, a pioneering startup where his beat was the magazine business, and his determination to be fair was as obvious as his charm.

Hey Terry,

David Carr from Inside.com here. I need to talk to you on Sunday if you happen to be checking email about some things. While credible people said nice things about you and the things you are doing . . . , they suggest US is tanking on the newsstand. I imagine that you have a thing or two to say about that and I’d like to print it.

Thanks for any attention. I have to file Sunday nite.

David Carr

Call on God, but row away from the rocks.—Hunter S. Thompson

Noting his signer, I called on Sunday night and spun some numbers at him. Us Weekly was selling 1.5 million per month on the newsstand, which was a threefold increase over its newsstand sales as a monthly. I said I was aware of the sniping and negative rumors that had, most likely, been coming from Time Inc., where apparently Us Weekly was viewed as some sort of threat to People because, I tossed in breezily, the women reading it were a younger demo and didn’t live in trailer parks. Plus, we were already outselling Entertainment Weekly by more than two to one on the newsstand after just 10 weeks as a weekly.

“Exactly,” David said. “Us Weekly is a weekly, so divide 1.5 million by four and see how that works.”

He was pointing out that we were selling 375,000 copies of the weekly, while People was still selling that same 1.5 million number we were bragging about as a monthly number but they were doing it every week. It was not a particularly relevant point, but his speed with circulation and advertising numbers made our conversations a back-and-forth game. Although he never let me win, I sometimes got the feeling that he was trying to give me a break. Good reporters can always make you think that. Another part of David’s charm was the careful curiosity that always defines a great reporter. It surprised no one when he was hired by the Times. When he wrote a piece about my arrival at Sports Illustrated, his angle was that I was coming in as a “well-traveled” outsider and an “agent of change.” Neither of us knew then that he would become so significant an agent in a media revolution that had not yet been named. That careful curiosity turned out to be perfect for the moment when old-school media companies got smashed in the mouth by digital.

So what if news found its own digital path. David broke stories anyway. He seemed to be everywhere, from the red carpet (where he wrote as “the Carpetbagger”) during the awards season in Los Angeles to throwing parties at SXSW in Austin. He was the star of Page One: Inside the New York Times, the notable 2011 documentary directed by Andrew Rossi about the paper. His column “The Media Equation,” in which he analyzed business and cultural developments in news, publishing and social media, became a “must-read”—to use jargon he would never touch. His intersecting contacts and sources across the platforms he covered both vertically and horizontally made his reporting like 3-D chess. By 2015 David Carr, the brand, was approaching half a million followers on Twitter.

David’s trip from a Minneapolis suburb through the University of Minnesota and on up a slippery career ladder (Twin Cities Reader, Washington City Paper, Inside.com, New York magazine, The Atlantic) to The New York Times was riled by various addictions. Finally kicking them left him straight and, I thought, benignly bitter. In Interview magazine, he told Aaron Sorkin that for a while he had been a low- bottom crackhead, sobered up for 13 years, and then decided to try to be a nice, suburban alcoholic and see how that would go. That lasted . . . Well, it ended in handcuffs, so it didn’t go great.

He was never aggressive about it, but he would occasionally drop the fact that he had been a single father on welfare or (so horrifying that you didn’t want to believe him) that he had beat up women. When we were out at night, as we were from time to time, he never seemed more unhinged than anybody else, though he could take shots at you just to let you know that maybe, just maybe, he knew more than you did.

One night we met at Joe’s Pub to see his friend Ike Reilly, whose indie-rock band, the Ike Reilly Assassination (“IRA, get it?” David said), was his longtime favorite. David sensed that I didn’t like the music as much as he did, and he kept turning his pack of Camel Lights over and over on the table until Ike joined us after his first set. I knew Ike had paid weird dues, like working for more than a decade as a doorman at the Park Hyatt in Chicago. His music was political and strong and I did like it, and I said so and we talked for a while about what music had been like when we were all younger.

The Accidental Life by Terry McDonell

“Terry’s been rocking that same haircut since high school,” David said. I think Ike said something about never getting any substantial coverage in Rolling Stone, which I had edited 20 years earlier, and he and David agreed that “the Stone” had always been kind of square. This was bait I had learned not to take, so no argument from me. Besides, Ike’s new album, Junkie Faithful, had just come out and it was strong and they were both drinking Diet Coke. I wondered how hard that was.

David was already a star and still rising at the Times when he published his 2008 memoir, The Night of the Gun, in which he reported out on himself—tracking down what really happened this or that time he was too drunk or stoned or both to remember clearly. The subtitle was A Reporter Investigates the Darkest Story of His Life—His Own. He looked at police reports and welfare documents and recorded 60 interviews—many with the people he had gotten high and in trouble with—and finally made his own sense out of the conflicting memories and the relentless question of whom to believe. His writing flowed and hit at the same time: Where does a junkie’s time go? [Mostly] in fifteen-minute increments, like a bug-eyed Tarzan, swinging from hit to hit.

It was brave, unfeigned work but David was shy about it when he sent me the bound galleys, emailing me in advance that he didn’t want to sound like a self-involved creep, but he was proud of the book, if not the story it told, and wanted me to read it.

I wrote back that it was acutely human and terrifying and somehow also hilarious and that I could only imagine the courage it had taken to get it so right. Later I hoped he was getting some pleasure, or at least satisfaction, from the success of the book as it climbed the best-seller list. In the Times Book Review, Bruce Handy noted, perhaps a little too cleverly, “In that conundrum [what was true and what was not in David’s memory] lie both the genius and a primary flaw of this brave, heartfelt, often funny, often frustrating book.” I got that, but I thought too that David had opened a very dangerous door for himself, yet then had been able to close it. In any case, his work at the paper seemed to me more and more ambitious as he took on what looked to me like the trickiest assignments he could get. Here’s one lede from the following spring:

Write about the media long enough and eventually you type your way to your own doorstep. Lately, when I finish an interview, most subjects have a question of their own.

“What’s going to happen to The New York Times?”

David answered the question with clear declensions of business plans and the various “levers” the company might use, and he hit every digital bumper.

I emailed him that the column was graceful and sharp and hard to do. I ended with “Hats off to you.” David came back to say that we were due for dinner at Odeon and suggested an additional “hats off ” to Ike, who had recently played a benefit in Minneapolis for a pal of David’s with six kids who was dying. At the end of it, Ike had walked up to David with a bag of $20,000 in cash—“Shades of the old days,” David wrote. “Great guy.”

He was always pulling his friends together, reconnecting people he had introduced, spreading credit around. In The Night of the Gun, he had written, I now inhabit a life I don’t deserve, but we all walk this earth feeling we are frauds. The trick is to be grateful and hope the caper doesn’t end any time soon. I especially liked “caper.” It made him appear lighter and less sentimental than he actually was. And I liked Ike more now, too.

When David died in 2015 of what turned out to be lung cancer, Simon & Schuster went back to press with The Night of the Gun. That was a Thursday night and it was ranked No. 53,570 on the Amazon best-sellers list. Twenty-four hours later, Amazon listed it as “temporarily out of stock”—and it had jumped to No. 7 on the overall list.

The tributes that came from what seemed like every possible direction reflected the crisscrossing of David’s eclectic reporting interests (media, culture, politics, technology), and all mentioned that he had been a junkie. But there was much more about his loyalty, his unselfishness as a reporter and what a steadfast mentor he had been to many. He was teaching by then at Boston University, which made complete sense because, as he would put it, aren’t reporters fundamentally teachers at heart, anyway? Educate yourself and then pass it on to as big an audience as you can find.

When I told David I might write about him, we met for an early dinner in the West Village. It was July 2014, seven months before his death, and he looked drained, thinner than I’d ever seen him, but he wasn’t acting tired. We talked about our children, and if either of us was ever really going to move to the country. His column that week was about the continuing importance of email as a source of news, but he wasn’t interested in going over any of that except to crack a little wise about his personal digital hierarchy, which started with email and then social media, with “the anarchy of the web” (as he had written) at the bottom.

I think I said something lame about news being news.

“Come on, man,” he scoffed. “It’s still just all about us.”

“Ha,” I said. He was mocking us sitting there about to dish wisdom over expensive pasta, poking at the self-importance of hacks who can’t help showing off even if, as David liked to say, they’ve been phoning it in from a great distance for a long, long time. He loved being a journalist but the journalism was more important and he knew that.

The next week, a photograph by Diane Arbus in The New York Review of Books stopped me. It looked just like David arriving in a suit and tie that night for our dinner, but it was of the Argentine magical realist Jorge Luis Borges. I couldn’t wait to show it to him.

This piece was adapted from the book The Accidental Life by Terry McDonell, copyright 2016 by Terry McDonell. Published by arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.