Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

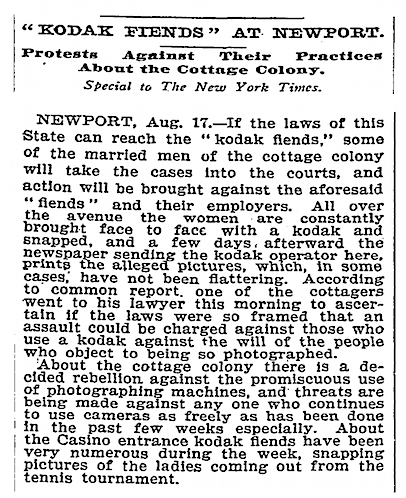

Jeff Jarvis reprints the clip above, in an article dismissing the privacy concerns surrounding Google Glass. The Victorian attitudes of Newport’s cottagers, he clearly implies, were misguided and misplaced. “Rest assured,” he writes. ” I will ask you whether it’s OK to take a picture of you in private.”

The key words, here — words which weren’t even part of the cottagers’ vocabulary — are “in private”. We now live in a world where we have public lives and private lives — and for over a century now, since roughly the point at which the above article appeared, the portion of our lives considered “public” has been expanding, while the portion of our lives we can consider “private” has been contracting. What’s more, Jarvis himself is a prominent proponent of the idea that we should maximize the speed at which we move our lives into the public realm; he also equates a desire for privacy with being “scared of the public” .

Never before have we faced so many opportunities to turn the formerly-private into the newly-public. As those opportunities arise, many people adopt them, and turn “public” into the new norm for such activities. Eventually, the norms become societally entrenched, to the point at which it is now utterly unobjectionable for those who once would have been labeled “kodak fiends” to take photographs outside a Newport tennis tournament.

My point here is that technology has a tendency to create its own norms. The classic example is the automobile — a technology which kills more than 30,000 Americans every year. From the 1930s through the 1990s, societal norms about who roads belonged to, and what people should do on them, were turned on their head thanks to the new technology. The dangerous new activity allowed by the new technology became the privileged norm, to the point at which just about all other road-based activity — and roads have been around for thousands of years, remember, since long before the automobile — essentially ceased to exist. Eventually, we reached the point at which elected representatives were happy saying that if a bicyclist gets killed by a car, it’s the bicyclist’s fault for being on the road in the first place.

If Google Glass — and wearable computing more generally — takes off and fulfills its potential, it will change society’s norms about what is public and what is private. It is therefore entirely rational, whatever you think of the set of norms we have right now, to assume that they will end up moving towards something more well disposed towards the new technology.

Jeff Jarvis will welcome that move, and can come up with dozens of reasons why it would be a good thing rather than a bad thing. “There’s no need to panic,” he writes. “We’ll figure it out, just as we have with many technologies–from camera to cameraphone–that came before.” But let’s be clear here about how much weight is carried by that “we’ll figure it out”. Realistically, “figuring it out” means, in large part, changing norms: irrevocably moving the line between what is private and what is public. That might be a good thing, it might be a bad thing. But if you like the norms we have right now — or if you think they’ve already gone too far in terms of robbing individuals of their privacy — then you have every reason to worry about what the onset of wearable computing might portend.

Update: Noah Brier points me to a quote from Daniel Mendelsohn, who goes back further still than the Victorians:

I am amused by the fact our word idiot comes from the Greek word idiotes, which means a private person. It’s from the word idios, which means private as opposed to public. So the Athenians, or the Greeks in general who had such a highly developed sense of the radical distinction between what went on in public and what went on in private, thought that a person that brought his private life into public spaces, who confused public and private, was an idiote, was an idiot. Of course, now everybody does this. We are in a culture of idiots in the Greek sense.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.