Everyone loves the Guardian—well, everyone except Rupert Murdoch, the British intelligence apparatus, the American intelligence apparatus, and bullies, sneaks, and abusers of authority everywhere.

But everyone else surely does, and no one more than us here at The Audit, where we judge Alan Rusbridger the premiere editor of his generation.

Exactly how much everybody loves the Guardian is going to be tested in the next few years, because the newspaper’s finances are not—repeat, not —good. It is on an ominous track and pursuing a strategy that is high-minded but also high-risk.

Alarmist? Let’s take a look.

The Guardian, by way of background, has a peculiar pedigree and is governed by unusual structure. Founded by a Manchester cotton trader in the early 19th century, it was bought by a longtime editor, C.P. Scott, who whose son in 1936 left it in a trust, the Scott Trust, run by his descendants [ADDING: for more, see Don Montague’s comment below]. The trust was converted to a “limited company” in 2008, but it basically serves the same function: “to sustain journalism that is free from commercial or political interference,” according to Guardian literature. The trust is the sole owner of a corporation named the Guardian Media Group (GMG), which in turn owns several units, including, famously, Guardian News Media (GNM), which is the “newspaper” in both its digital and print forms, along with an online dating service, and other small businesses.

The important point here is that unlike The New York Times and The Washington Post, the Guardian is not ultimately part of a commercial enterprise. It doesn’t need to grow financially. It just needs to not lose too much.

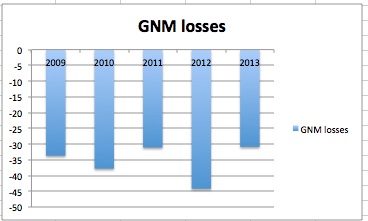

Trouble is, GNM, the news organization, is losing too much. Indeed, as many people know, it is a huge money loser.

How huge? Put it this way: The group doesn’t even talk about profits for GNM, only getting losses to “sustainable levels.” Right now, they are not. Here’s what they look like for the past five years (the figures are in millions GBP).

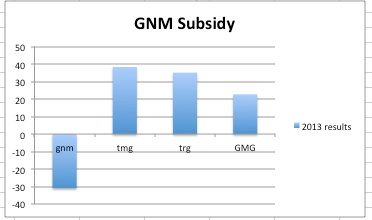

Fortunately for the Guardian, and the free world, the Trust owns other businesses that are part of the larger Group. The two main things are a big stake in Trader Media Group, which owns Auto Trader, a nicely profitable auto classified ad operation, and Top Right Group, which does event planning and the like.

In 2013, for instance, the two trade operations earned enough to push the whole group into a profit.

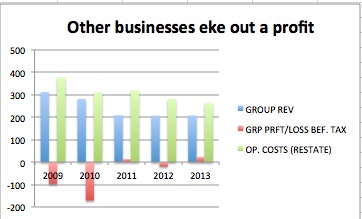

But, that has decidedly not always been the case. As we can see here, the entire Group—never mind the GNM—has posted losses in three of the past five years (the figures exclude the results from former businesses. If they had been included, the 2012 loss would have been much higher).

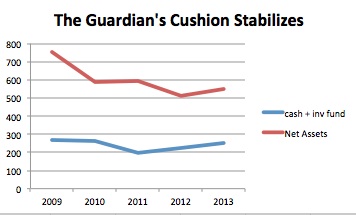

The Guardian‘s ace-in-the-hole is the Trust and its investment fund, which exists to subsidize the paper and which, after taking some hits in the financial crisis, has stabilized. The important number is the blue line, the cash and investment fund:

Still, this is not a bottomless cookie jar.

As Ken Auletta noted in his recent takeout on the paper (with my emphasis):

Still, the Guardian lost more money this past year than it did in fiscal 2007-08. To run its print and online operations, the Guardian employs sixteen hundred people worldwide, including five hundred and eighty-three journalists and a hundred and fifty digital developers, designers, and engineers. “The toughest critique of Alan is that he has not faced up to the Guardian’s costs,” a longtime executive at the paper said. The newsroom “is too big for a digital newspaper.”

And:

[GMG CEO] Andrew Miller admits that he does not foresee the newspaper earning a profit anytime soon. Rusbridger said, “The aim is to have sustainable losses.” Miller defines that as getting “our losses down to the low teens in three to five years.” But at some point, if the Guardian does not begin to make money, the trust’s liquid assets, currently two hundred and fifty-four million pounds, would be depleted.

Correct.

Now, we’re big advocates of paywalls around here, in general, for legacy news organizations, especially when nothing else is working. The paywall debate has been cast in quasi-religious terms, and Ryan Chittum and I are supposed to be paywall haredi or something, but as we’ve said like a million times, they’re a tool that can, if used correctly, add an income stream to news organizations while costing next to nothing in traffic, digital ads, and reader engagement. The breakthrough, the innovation–to steal back a phrase favored by free-content proponents—was the NYT’s metered model introduced in 2011 and copied around the world.

A paywall, done right, can be seen as essentially free money. You set the meter high enough to not impact your pageviews and uniques and get whatever you can from your core readers.

The Guardian‘s Katharine Viner the other day eloquently made the case for the transformative power of open journalism and against paywalls. The philosophical discussion is one for another day, but I’d only say here that the question is not nearly as binary as many seem to believe.

One reason we’re inclined to like metered subscription models—all else being equal—is that they debunk the annoying and now disproved idea that journalism has no value in the marketplace. And they provide incentives for quality that click-chasing models, those based on sheer volume of posts and traffic, do not.

We were adamant, for instance, that The Washington Post needed one because its digital revenue had been flatlining for years at relatively low levels. With digital ad rates continuing to decline, asking online readers to contribute was an obvious move, especially since experience has shown the loss of traffic and digital ad revenue is not really material.

The Guardian has its own reason for eschewing paywalls. One is practical: the BBC employs thousands of journalists and is free. Why, then, would people pay for the Guardian? Another is ideological, and not in a pejorative sense. “Open journalism” is just part of the Guardian‘s, and the Trust’s, ethos, part of their identity. It’s hard not to respect that.

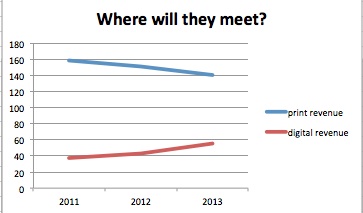

A third reason is that, unlike at other places, digital revenue is actually growing and growing at a respectable pace—from £37.4 million in fiscal 2011 to £55 million in 2013, a rise of nearly 50 percent in two years, accelerating to 28 percent in the last year alone, eclipsing the decline in print revenue.

The Trust’s executives are pleased with the direction of the company, and this is understandable. This dame here, Dame Amelia Fawcett DBE, chair of the GMG, says:

At Group level, we were pleased to convert last year’s loss into a profit before tax, while EBITA also improved. This is due in no small part to the success of our transformation plan, as we continue to map our way towards the digital future.

And this, uh, gent, Miller says:

The financial impact of our digital-first strategy, launched two years ago, is clearly demonstrated in our performance in 2012/13. A sharp increase in the contribution of our digital operations to revenue was a striking feature, enabling a modest increase in overall Group revenues. Having committed to digital earlier than our peers, we are now reaping the benefits.

Digital revenue, importantly, includes some subscription income via apps for phones and tablets.

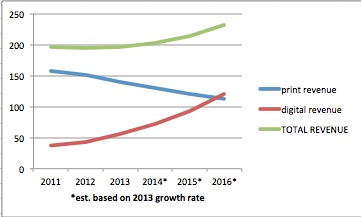

Hey, if you assume similar growth for the next few years, you are looking, dames and knights, at a fairy tale ending—total revenue actually rising:

All we can do is root for that kind of growth to continue but, also, to recognize it’s very, very unlikely. For one thing, it’s just harder to achieve that kind of growth off of a larger base. Even the Times‘s vaunted digital subscription growth eventually fell to earth and stabilized. Betting the Guardian on growth continuing at that rate is folly.

The stakes are quite large. The Guardian is formidable today precisely because of those 583 journalists and 150 digital developers. There is no free online-only news organization anything close to that size. The Group is already taking £25 million out of the organization in cost savings, and that’s fine. But obviously cutting alone is not the answer.

So, no paywall? Sure. Let it ride, for now.

But realistically, chances are that within the next few years, digital growth will level off while the print side continues its steady decline. Not that I want this. Just that that’s what’s likely to happen.

At that point, if the goal is still to get the losses into the low-teens, it will be time to turn to readers for help, as they already are on tablets and phones.

As the Lord Protector might say, trust in open journalism, but keep your powder dry.

Dean Starkman Dean Starkman runs The Audit, CJR’s business section, and is the author of The Watchdog That Didn’t Bark: The Financial Crisis and the Disappearance of Investigative Journalism (Columbia University Press, January 2014). Follow Dean on Twitter: @deanstarkman.