As the 2016 Republican presidential primary draws to a close, it is worth noting that part of Donald Trump’s popularity can be attributed to his use of social media. From his late night Twitter rants to the official announcement Friday of his vice-presidential running mate, Indiana Governor Mike Pence, Trump has done a superb job of using social media to garner both mainstream media attention and the public’s eye. But just how important has social media strategy become in campaigning? One way to answer that question is to look at the social media strategies of two of Trump’s failed competitors: Ben Carson and Carly Fiorina.

A project supported by the Tow Center for Digital Journalism and Syracuse University’s Center for Computational and Data Sciences tracks the Twitter and Facebook feeds of active presidential campaigns. The project, Illuminating 2016, looks at the number of messages each candidate sends, and also codes by message type. By doing so, this tool is able to provide details about candidate social-media usage that typically do not register on the mainstream media’s radar.

There are a few strong similarities between the trajectories of the Fiorina and Carson campaigns. Both proudly touted their status as outsiders to politics—Ben Carson as a well-known neurosurgeon and Carly Fiorina as first female CEO of a top-20 US corporation, Hewlett Packard. Both enjoyed a brief period of popularity followed by a precipitous drop in poll numbers. However, the momentum that Carson and Fiorina experienced was short lived. And after each languished in the polls for four months, both candidates suspended their campaigns.

Both candidates, as shown by the Illuminating 2016 site, likely under-utilized social media when they probably should have used it most. There is no evidence that either candidate’s social media utilization patterns influenced his or her performance in the polls. Comparing their social media behaviors to their performance on the campaign trail, however, does reveal a disparity between social media strategies and what each candidate faced offline.

One might have expected, for instance, that Fiorina and Carson would use social media to leverage favorable polling numbers. But neither campaign showed a significant increase in the total messages following his or her peak in the polls.

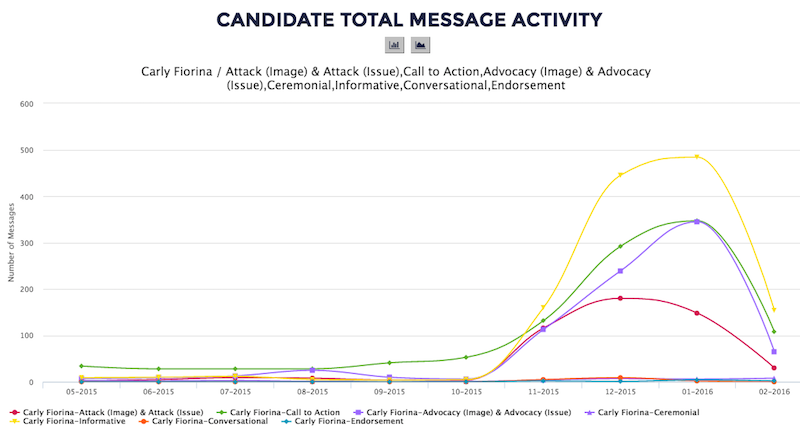

One might have expected, for instance, that Fiorina and Carson would use social media to leverage favorable polling numbers. But neither campaign showed a significant increase in the total number of messages posted on social media in the month following his or her peak in the polls. After strong performances in the Republican Party’s first two debates, Fiorina found herself in second place behind Trump in a national CNN poll conducted September 17–19. The Fiorina campaign posted 63 Facebook and Twitter messages in September, the same month the Voter Gravity and CNN polls were released. In October, the total increased by only six posts. By comparison, Trump posted 60 total messages in September and 466 in October. Fiorina’s poll numbers dropped to single-digits in November and never rebounded.

Total message activity for Carly Fiorina’s Twitter and Facebook accounts, broken down by message type. Source: Illumination 2016.

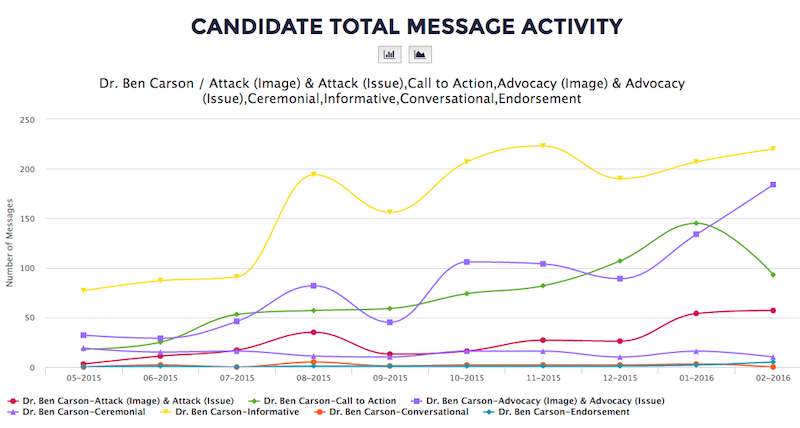

Carson’s peak in the polls came in late October, when a CBS/New York Times poll gave him a 26 percent to 22 percent advantage over Trump. Although Carson’s lead in this poll was within the margin of error—and Trump had a consistent lead in most polls both before and after the CBS/NYT October anomaly—it is interesting to note that his short lead followed significant media coverage of controversial statements he made about Muslims, Obamacare, guns, and several other topics. The Carson campaign sent 422 Facebook and Twitter messages in October, the same month the CBS/New York Times poll was released. During November, the campaign posted only 32 more messages than it did in October. Trump’s message count, on the other hand, increased 49.6 percent to 697 in November. November, coincidentally, was the beginning of Carson’s decline in the polls.

Total message activity for Ben Carson’s Twitter and Facebook accounts, broken down by message type. Source: Illumination 2016.

The Illuminating 2016 website also categorizes and codes candidate social media posts by message type. The kind of comments candidates post online, and the frequency of these messages, suggests a lot about the connection between social media strategy and ground game. For instance, what Illuminating 2016 calls “advocacy-image” messages convey positive information about the candidate’s character, personality, or ability to lead. “Advocacy-issue” messages, on the other hand, talk about the candidate’s policy positions. When a candidate does well in the polls, these messages can be used to highlight those poll numbers and the candidate’s strengths.

Fiorina had two stellar debate performances during the first half of her campaign, which contributed toadv her quick but short-lived rise in popularity. But instead of capitalizing on her early success by immediately leveraging social media to talk about her strengths as a candidate and create discussion about her policy positions, it was almost an entire month before Fiorina’s team increased the number of advocacy posts. The campaign posted fewer than 20 advocacy messages in September and October combined. By this time, she had already lost much of the support that followed her early debate performances.

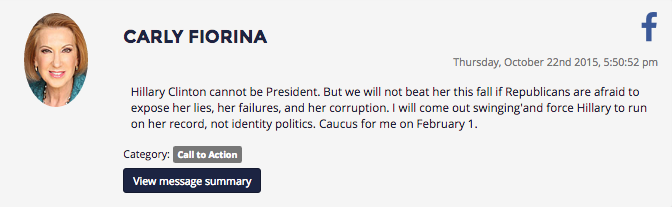

One example of a call-to-action Facebook post from Carly Fiorina. Source: Illumination 2016.

Instead, Fiorina mostly used social media to ask people to take action before and immediately after her campaign reached its peak. Sixty-five percent of camp Fiorina’s 63 messages posted in September, and 77 percent of the 69 posted in October were calls to action—which direct people to engage in activities offline (e.g., volunteering, attending an event, etc.) or online (e.g., visiting a website, retweeting something, watching a video, donating money, buying campaign merchandise, voting, etc.).

Carson’s campaign, on the other hand, more than doubled the number of advocacy messages in the same month as the CBS/NYT poll. Of 106 messages posted in October, 25 were posted a couple days after the poll was conducted. The team maintained this level, posting another 105 advocacy-related messages in November. So, Carson’s strategy did seem to change in the same month as the poll that suggested he was the front-runner. However, nearly half of the updates the Carson campaign posted on social media in October and November were informative in nature, meaning the messages consisted of neutral information about the campaign or an event—without making any explicit appeal to followers.

One example of an advocacy post on Facebook from Ben Carson.

Informative and call-to-action messages made up 63.1 percent of all posts from the Carson campaign between November and February and 62.1 percent of all posts from Fiorina campaign between October and February. By contrast, 42.9 percent of Trump campaign social media posts between October and February were informative and call to action messages. The high percentage of these messages suggests both campaigns made distributing information and getting people to participate in the political process a higher priority than advocating for the candidate and his or her policy positions. However, this strategy did not fit the realities they faced. By the time Fiorina and Carson made significant adjustments to their social media strategies, their campaigns were already on life support.