Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Is the sky falling for Obamacare?

You might think so from reading the press these days. On Monday, National Journal published a piece by Josh Kraushaar with the headline “Why Obamacare Is On Life Support” and a subhed that predicted “Democrats may begin calling for repeal if the law’s problems don’t get resolved soon.” CBS News’s Jake Miller also asked “Is the Affordable Care Act in serious jeopardy?” and Politico’s Todd Purdum went even further, warning of “Obamacare’s threat to liberalism.”

It’s true, of course, that the rollout of the new insurance exchanges has gone much more poorly than the administration expected, raising concerns among members of Congress, including Democrats who normally back Obama. The issue has become sufficiently damaging that 39 vulnerable House Democrats even voted in favor of a GOP healthcare bill. But the legislation has no chance of becoming law, which allowed those Democrats to cast a free vote that distanced themselves from the current controversy without actually undermining their party’s policy objectives.

Journalists are extrapolating wildly from this starting point, imagining an unfolding political catastrophe that somehow induces Democrats in Congress to override a presidential veto and repeal their party’s signature domestic policy achievement of the last 30 or more years. It’s a highly unlikely outcome, as I tried (and failed!) to convince Kraushaar on Twitter yesterday. Modifications to the legislation will surely occur in the future, but major steps toward repeal such as rolling back the Medicaid expansion, withdrawing insurance subsidies, shuttering the exchanges, or allowing insurance companies to again deny coverage to consumers with pre-existing conditions seem improbable absent catastrophic, years-long failures far beyond what we’ve seen to date.

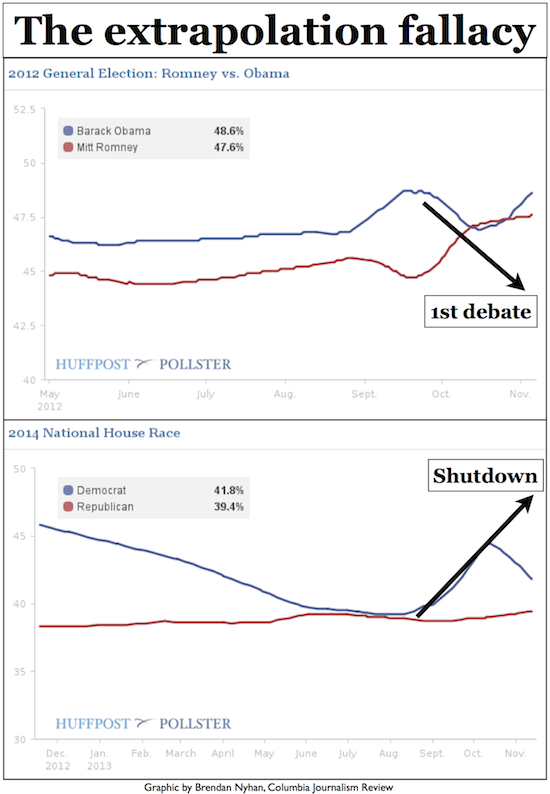

If you’re feeling some déjà vu, there’s a reason–these journalists are falling victim to the same extrapolation fallacy that pervades so much political coverage. In these sorts of stories, reporters identify a current trend and spin out a story in which it continues to implausible extremes. Consider two recent examples: the decline in President Obama’s standing in the polls after his first debate with Mitt Romney and the surge in Democrats’ standing in the generic House ballot during the government shutdown. In both cases, journalists extrapolated wildly from a short-term trend, hyping Romney’s “momentum” and the damage to the Republican brand and suggesting that the trends would continue in the direction indicated by the arrows in the graphs below.

But as the graphs show, any shifts in public opinion around those events were transitory.* Romney’s standing in the polls stabilized soon after the first debate. Likewise, the GOP quickly shifted from defense to offense after the media’s attention shifted from the shutdown to the healthcare rollout. While it is possible to imagine alternative scenarios (see, e.g., the breathless reporting in the 2012 campaign retrospective Double Down on how Obama narrowly averted a disastrous second debate), the reality is that national politicians and parties rarely self-destruct on the level that these predictions require. Democrats now face a policy challenge that is more difficult than overcoming a poor debate performance, but it is likely that the administration will fix enough problems to maintain party cohesion and prevent repeal, particularly once they can highlight benefits from the law that will become available in January.

The problem, of course, is that predicting the persistence of the status quo is boring. Journalists have strong incentives to inflate the likelihood of worst-case scenarios for whoever is losing the current news cycle, which produces a lot of phony “game changers”. After so much hype and so many failed predictions, who can blame citizens for tuning these stories out?

* The labels and arrows on the graphs are intended to be illustrate the perceived effect of the events in question rather than their actual timing or impact–please consult the original Huffington Post Pollster poll averages for the 2012 presidential campaign and the 2014 House generic ballot for more details. The first Obama-Romney debate took place on Oct. 3, 2012, and the shutdown lasted from Oct. 1-17, 2013.

Follow @USProjectCJR for more posts from this author and the rest of the United States Project team.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.