Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

As the anchor of the evening news for RTE, Ireland’s national broadcaster, Caitríona Perry couldn’t walk down the streets of Dublin without attracting a crowd. So when she moved to the US to take on the role of chief presenter for the BBC in Washington, in August of 2023, she found the anonymity refreshing. Then, in the run-up to the US presidential election, things started to change. People began stopping Perry on the street, even as she was coming out of the CVS with her daughter. “I took it to be a good sign that more people were watching,” Perry told me. “But not a scientific measure.”

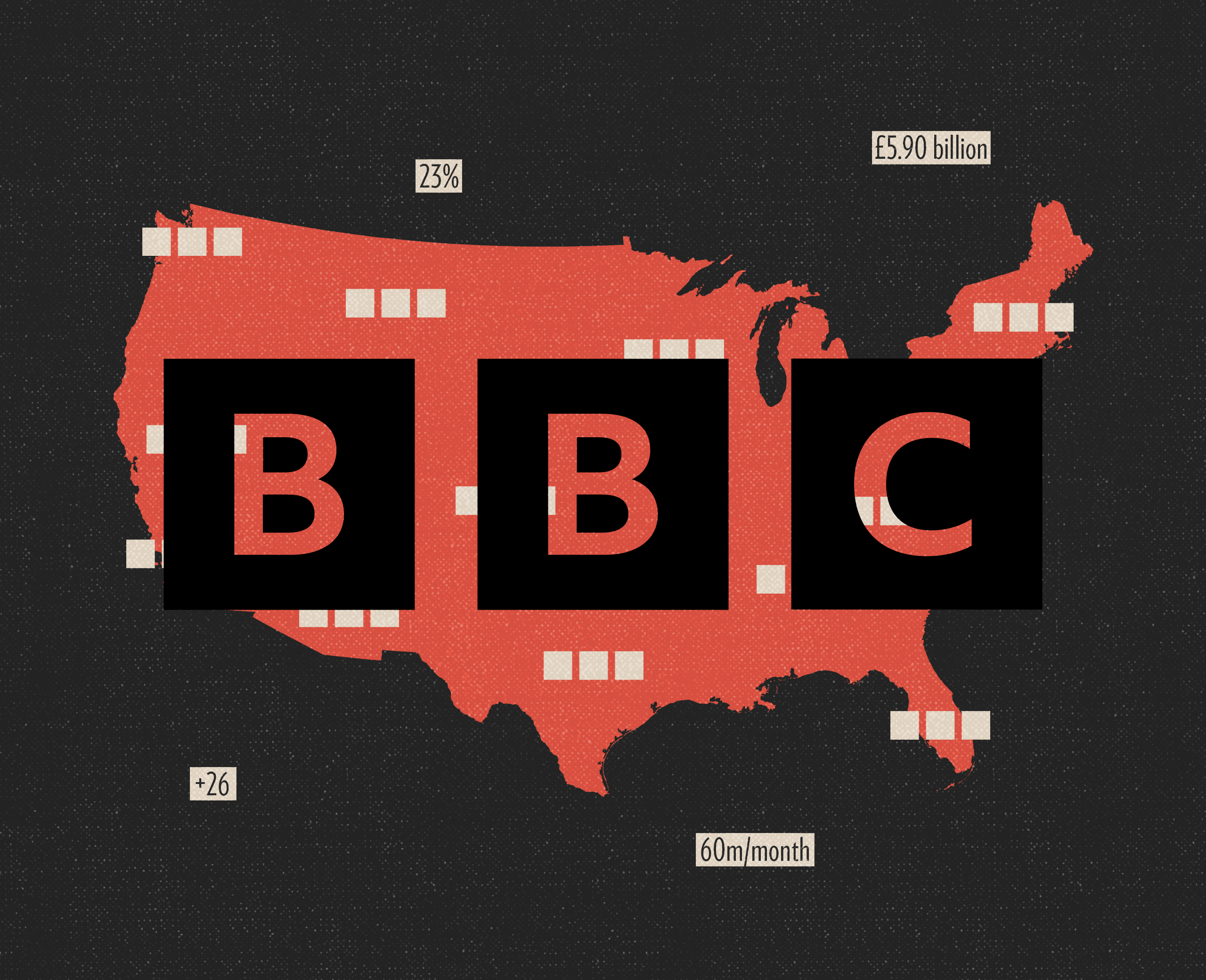

According to Allison Rivellini, a BBC spokesperson, the site received a record seventy-seven million US visitors in September. That moved it up seven spots in the news category compiled by Comscore, a private analytics firm that measures audiences across platforms, to its highest ranking ever, putting the BBC ahead of the AP, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post. The latest YouGov survey ranked the BBC second in terms of trust, trailing only the Weather Channel.

In the past three years, while Brits have descended on American media broadly, the BBC has doubled its US reporting team. Perry serves as a chief presenter, alongside Sumi Somaskanda, for BBC News, broadcast from Washington during US prime time. Viewers can watch on cable, across various streaming platforms, or via livestream on the website. The range of digital content on the website includes a live feed, news analysis, specialized podcasts, and documentaries—all aiming to establish competitive advantage in a crowded US media market by highlighting the BBC’s institutional commitment to impartiality, its global sensibility, and its big-picture approach to American political news. “We don’t have a dog in the US political fight as an organization, and our audiences can feel that in our coverage,” Kevin Ponniah, the BBC’s regional director for the Americas, told me.

A critical breakthrough came in July of 2024, when Gary O’Donoghue, the BBC’s chief North America correspondent, reported on the attempted assassination of Donald Trump in Butler, Pennsylvania. O’Donoghue conducted an interview with an eyewitness who had observed the shooter crawling across a roof and tried to point him out to law enforcement; the segment went viral. O’Donoghue, rumpled and disheveled after hurling himself to the ground, came across as the antithesis of a puffed-up TV correspondent as he listened to the witness with empathy and concern. This past July, a year after the shooting, Trump called O’Donoghue and gave him an interview. (Asked if the assassination attempt had changed him, Trump responded, “I like to think about it as little as possible.”)

Under the terms of a royal charter, the BBC is funded in the United Kingdom by a license fee of 174.50 pounds a year (233 dollars) per household. The license fee accounts for two-thirds of the BBC’s annual revenue of 5.90 billion pounds; much of the remainder comes from licensing agreements and other commercial arrangements under the auspices of BBC Studios, the organization’s commercial arm. (The Bluey franchise and Dancing with the Stars are both major moneymakers.)

The charter also mandates that the BBC “act in the public interest” by providing impartial coverage. But BBC.com is a commercial venture. Ben Goldberger—the executive director of editorial content at BBC Studios, who served as executive editor of Time magazine from 2019 to 2023—told me there’s a “direct line” between the revenue generated by BBC.com and the funds that, for instance, put journalists on the ground in Ukraine: if the site makes a profit, that money is plowed back into the BBC’s public interest programming, including the news. That means success depends on convincing Americans not just that they should visit the site but that they should pay, something that US news consumers have been notoriously unwilling to do. When I spent some time clicking around, I didn’t hit the paywall until I tried to stream the live feed for the third time. Then a window popped up asking me to subscribe for $49.99 a year or $8.99 per month. I asked BBC Studios how many Americans had ponied up, but no one would say.

The subscription strategy brings BBC.com into direct competition with US media juggernauts—the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and, notably, CNN, which launched its all-access streaming service last week. It’s also worth noting that this is not the BBC’s first foray into the American market: starting in 2007, BBC World News America aired on cable and many PBS stations. It gained a dedicated following and won several Peabody Awards, but never attracted a mass audience.

This time around the BBC is putting far more resources into its US strategy. The stakes are much higher, given the significant challenges to the BBC’s financial model in the UK: the royal charter, whose license fee has kept the newsroom in operation since 1946, will expire at the end of 2027. The government of Keir Starmer, the prime minister, is studying a range of new approaches. The BBC is facing competition from commercial broadcasters and streaming services and has been subject to a whirlwind of criticism over its coverage of the Gaza war: pro-Palestinian activists accuse the BBC of normalizing genocide; backers of Israel claim it is whitewashing Hamas.

Within the US, there are reasons to root for the BBC. At a time when the Trump administration has slashed funding for public media, it’s heartening to see that many Americans are attracted to what the BBC has to offer. I also believe, as I’ve argued before, that there is a real value in covering the US like a foreign correspondent, stepping back from the political fray and engaging with the full spectrum of Americans and listening sympathetically to their concerns.

That’s certainly been the experience for Caitríona Perry. She told me she loves DC for its low-slung buildings, its diverse community, its access to nature, and—I’m not kidding—its “amazing climate,” at least for someone escaping the Irish gloom. But Perry said she really learned about America during extended road trips. In 2016, as a correspondent for RTE, she traveled through the Midwest, where she met Americans who told her the prospect of getting ahead was a “pipe dream.” As Perry said, “I was just struck time and again by people who were working who had these challenges and felt that they weren’t being served well by the existing politicians and the existing political structure.” She predicted Trump would win the election, despite the polls.

As a newly minted BBC presenter she traveled widely again last fall, visiting swing states in advance of the 2024 election. I asked Perry if she encountered hostility from Trump supporters and epithets of “fake news.” “There can be, in certain circumstances,” Perry said. “But as soon as I start speaking, and they hear that I’m not American and I have an Irish accent, then a lot of that fades away. They’re like, ‘We thought you were one of the American networks. But you’re the BBC. You guys listen to everyone.’”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.