Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Last week, OpenAI released Atlas, which joins a growing wave of AI browsers, including Perplexity’s Comet and Microsoft’s Copilot mode in Edge, that aim to transform how people interact with the Web. These AI browsers differ from Chrome or Safari in that they have “agentic capabilities,” or tools designed to execute complex, multistep tasks such as “look at my calendar and brief me for upcoming client meetings based on recent news.”

AI browsers present new problems for media outlets, because agentic systems are making it even more difficult for publishers to know and control how their articles are being used. For instance, when we asked Atlas and Comet to retrieve the full text of a nine-thousand-word subscriber-exclusive article in the MIT Technology Review, the browsers were able to do it. When we issued the same prompt in ChatGPT’s and Perplexity’s standard interfaces, both responded that they could not access the article because the Review had blocked the companies’ crawlers.

Atlas and Comet were able to read the article for two reasons. The first is that, to a website, Atlas’s AI agent is indistinguishable from a person using a standard Chrome browser. When automated systems like crawlers and scrapers visit a website, they identify themselves using a digital ID that tells the site what kind of software is making the request and what its purpose is. Publishers can selectively block certain crawlers using the Robots Exclusion Protocol—and indeed many do.

But as TollBit’s most recent State of the Bots report states, “The next wave of AI visitors [are] increasingly looking like humans.” Because AI browsers like Comet and Atlas appear in site logs as normal Chrome sessions, blocking them might also prevent legitimate human users from accessing a site. This makes it much more difficult for publishers to detect, block, or monitor these AI agents.

Furthermore, the MIT Technology Review, like many publishers including National Geographic and the Philadelphia Inquirer, uses a client-side overlay paywall: the text loads on the page but is hidden behind a pop-up that asks a user to subscribe or log in. While this content is invisible to humans, AI agents like Atlas and Comet can still read it. Other outlets like the Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg use server-side paywalls, which don’t send the full text to the browser until a user’s credentials are verified. Once a user is logged in, the AI browser can read and interact with the article on their behalf.

OpenAI says that, by default, it does not train its large language models on the content users encounter in Atlas unless they opt in to “browser memories.” Pages that have blocked OpenAI’s scraper will still not be used for training, but “ChatGPT will remember key details from content you browse.” As Geoffrey Fowler of the Washington Post wrote last week, “the details of what Atlas will or won’t remember get confusing fast.” It remains unclear how much OpenAI is learning from paywalled content that users are unlocking for the agents to read.

We did find that Atlas seems to avoid reading content from media companies that are currently suing OpenAI. (We did not observe the same with Comet.) However, when we prompted Atlas to interact with these publications, it employed various work-arounds to try to satisfy our requests.

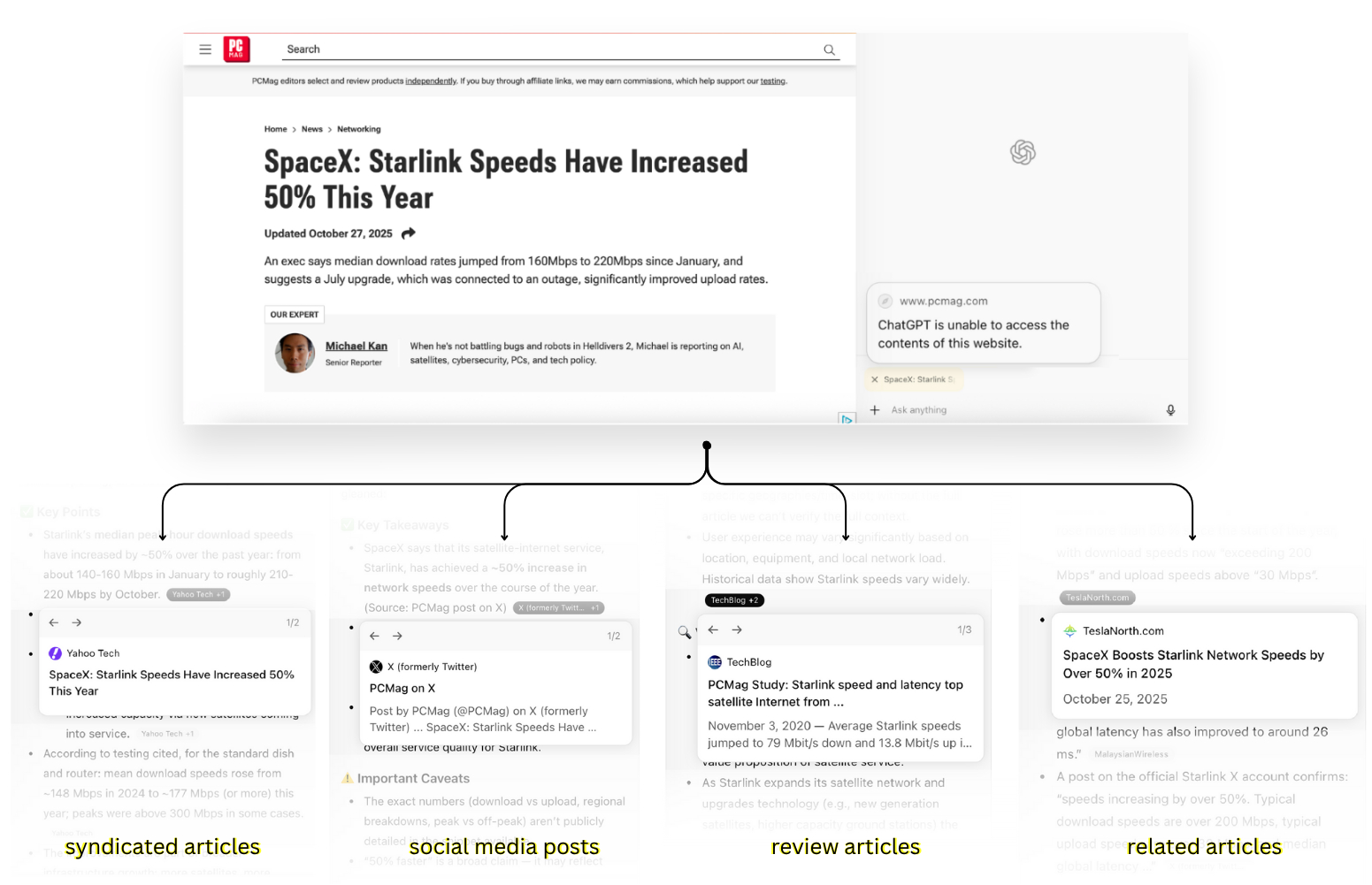

For instance, when we prompted Atlas to summarize an article from PCMag, whose parent company Ziff Davis sued OpenAI for copyright infringement in April, the agent produced a composite summary, drawing on tweets about the article, syndicated versions, citations in other outlets, and related coverage across the Web. Online research expert Henk van Ess first documented this behavior in July, observing that AI agents can reverse-engineer an article using “digital breadcrumbs.”

When we asked Atlas to summarize an article from the New York Times, which is also suing OpenAI, it took a different approach. Instead of reconstructing the article, it generated a summary based on reporting from four alternative outlets—The Guardian, the Washington Post, Reuters, and the Associated Press—three of which have licensing agreements with OpenAI.

By reframing the user’s request from a specific article to a general topic, the agent reshapes what that user ultimately reads. Even when a media outlet is able to prevent the agent from accessing its content, it faces a catch-22: the agent simply suggests alternative coverage.

AI browsers are still new, and we don’t know whether they will replace existing ways of searching the Web. But whether or not these tools achieve widespread adoption, one thing is clear: traditional defenses such as paywalls and crawler blockers are no longer enough to prevent AI systems from accessing and repurposing news articles without consent. If agents are the future of news consumption, publishers will need greater visibility into, and control over, how and when their content is accessed and used.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.