A joint convention put on by membership organizations representing black and Hispanic journalists is drawing thousands to Washington, DC, this week and may set a template for how such groups can work together in the future. It’s a major breakthrough five years after financial discord led to an ugly breakup for an umbrella coalition of journalism organizations representing minority groups and advocating for better representation in newsrooms.

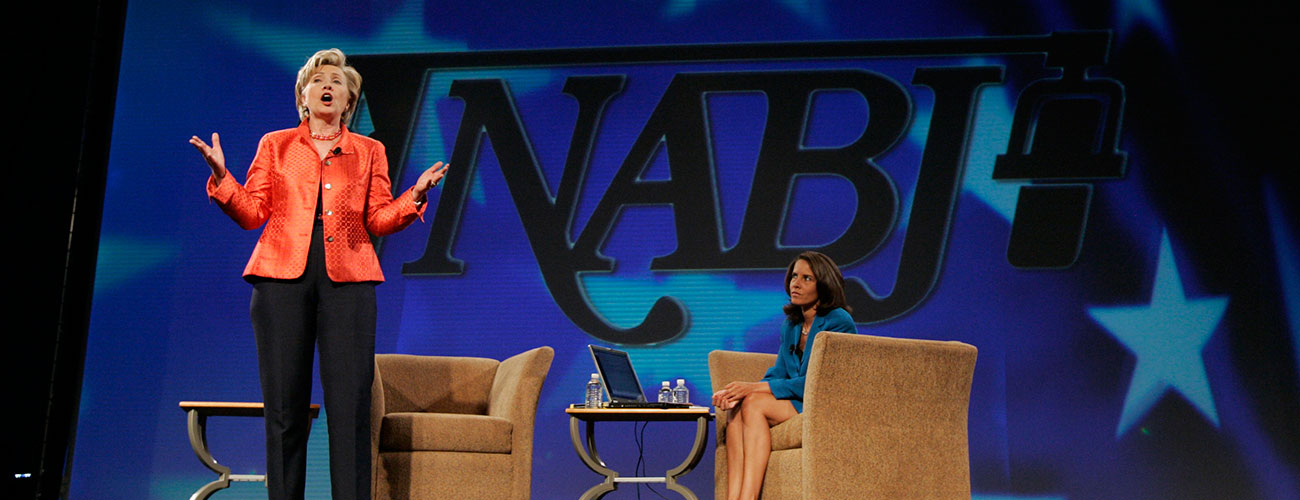

The convention, organized by the National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) and the National Association of Hispanic Journalists (NAHJ), is expected to be the largest gathering of minority journalists in the US since 2008. BuzzFeed reports 4,000 attendees are expected to learn from veterans of the industry and hear from speakers, including presidential candidate Hillary Clinton. Journalists representing other affinity organizations including the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association (NLGJA) and Native American Journalists Association (NAJA) will also be present.

While members and officers of the affinity groups regularly network with each other and attend each other’s events, this is the first time since the breakup of the umbrella group UNITY that former members of the coalition have hosted a joint convention. UNITY itself has soldiered on as a coalition of NLGJA, NAJA, and the Asian American Journalists Association (AAJA)–each of which has an equal voice in UNITY while also operating independently–while NABJ and NAHJ have had no formal ties to UNITY since the split.

A greater sense of teamwork among the organizations, particularly at a time of declining newsroom resources, should help the broader mission of diversifying newsroom staffs, particularly in leadership ranks, where representation is particularly weak. The sad fact is journalists of color make up less than 13 percent of newsrooms, according to The American Society of News Editors, well below the more than 30 percent of Americans who belong to minority groups. Cooperation could also bolster the financial prospects of the groups, by enabling savings on event planning costs like food and hotel arrangements as well as providing a larger platform for potential sponsors.

Already, there are signs an ongoing partnership could pay dividends: ABC, Bloomberg, ESPN, and The Wall Street Journal are just a few of the big name organizations participating in the career expo for an opportunity to network with attendees; sponsors include Coca-Cola and Toyota; and the conference landed Hillary Clinton–who is popular with black and Hispanics voters–as a Friday keynote speaker.

“I am really happy this year that we are having a joint convention,” says Joanna Hernandez, past president of the coalition UNITY: Journalists of Color, Inc., who has missed the energy, opportunity to get together regularly, and the excitement from when the groups met as one.

The black and Hispanic journalism groups decided to come together for three main reasons: A common goal to help journalists of color navigate the industry, to offer black and Hispanic journalists their own convention, and for the financial benefit of sharing costs, says past NAHJ president Hugo Balta, senior director of multicultural content at ESPN. Financial efficiencies are a major selling point for each organization, as both have struggled to break even in recent years.

NABJ in 2014 lost about $260,000 on total revenue of about $2.3 million, while NAHJ earned just $15,000 on total revenue of $917,471, according to forms nonprofit organizations are required to file annually with the IRS. NABJ president Sarah Glover told The Root the organization plans to reduce costs in 2016 via the joint convention and eliminating three in-house positions. NABJ spokesperson Aprill Turner did not respond to request for comment on that organization’s financial state.

“It is an expensive proposition especially when you are a non-profit organization,” says Gregory Lee, NABJ member and past treasurer. “For the most part groups get most of their revenue from the convention.”

Rates for attendees of this year’s convention ranged from $225 to $500 per person depending on which rate applies. Meantime, exhibitors were charged fees ranging from $2,800 for journalism schools to $85,000 for high-end exclusive sponsorships.

This conference is an opportunity to see old friends and reconnect with the other groups, said Hernandez, who is currently the director of diversity initiatives at CUNY. While she was always an advocate of UNITY, she acknowledges that, “maybe that time has come and gone.”

So you may be wondering why these groups chose to leave UNITY, if there are financial benefits in collaboration. The problems started when NABJ leadership voiced concerns about the breakdown of financial proceeds for UNITY members. According to Richard Prince’s Journal-isms, UNITY in 2011 kept 20 percent for its own administration, split 40 percent evenly among the four partnered organizations, and split the other 40 percent based on registration percentages for each group.

NABJ, the organization with the highest revenue, felt it was unfair how the proceeds were split. The group comprised more than 50 percent of UNITY members, and the group’s leaders believed the funds should better reflect their majority. After many attempts to work through disagreements and make amends, NABJ decided to leave in 2011. Within two years, NAHJ came to a similar conclusion after facing some of the same issues, and decided to pull out of UNITY as well.

It was not an easy decision for either group, especially as the recession continued to take a toll on the news industry. The future of journalism remains uncertain. Newspaper reporters, photojournalists, and broadcaster were rated among the 10 worst jobs for 2016. Declining circulations, falling ad revenues, and troubling audience numbers have led to belt tightening for news organizations, and that means belt tightening for the associations serving journalists. And dark clouds remain: The Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts a 9 percent decline in the number of jobs that will be available for journalists over the next 10 years.

The very real possibility of having fewer journalists of color in the industry as a whole cannot be ignored when looking at the number of members affinity groups can realistically attract. Bringing the groups together could give them strength in numbers–more members, and potential savings on administrative costs. However, many members remain skeptical.

It would take an “open mind and understanding of every group’s needs” for a new alliance to work, says Lee, who is the director of content at the National Basketball Association. The lack of understanding is what led to the fallout, he says.

It’s been three years since NAHJ left UNITY, and about five for NABJ. The feud wasn’t entirely about financials: Critics accused UNITY of losing sight of its mission–particularly after it welcomed the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association (NLGJA) to the coalition in 2011, and changed its tagline from “Journalists of Color” to “Journalists for Diversity.”

Some felt the inclusion of NLGJA took away from UNITY being about journalists of color because NLGJA was mostly white, as Tracie Powell noted in an earlier CJR piece. “Who cares about the names, let’s focus on our mission,” says UNITY president Russell Contreras. He understands the fear of expansion, but he emphasized that gay white males do not enjoy the same privilege as their straight counterparts. NLGJA executive director Adam Pawlus adds in an email that his group shares a mission with compatriot affinity groups: to push for “accurate coverage about diversity” and for news organization staffs that “reflect the country’s diversity.”

UNITY decided not to hold a convention this year, skipping its traditional four-year rotation in favor of smaller regional events. Since Contreras became president in 2015, he has worked to redefine the goals and mission of the group, including a new focus on topical training activities in poverty stricken areas around the country. Among its events was a conference in Phoenix on the topic of immigration and a regional conference on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.

Contreras noted “tensions” between UNITY and other journalism affinity groups have faded with time and the departure of many of the key players in the dispute.

The groups that remain under the UNITY umbrella continue to operate independently as well: NAJA’s total revenue in 2014 was $343,373 while NLGJA’s was $552,789, and AAJA drew in the most at $1,356,808, according to government filings. UNITY’s total revenue that year was $101,240. Contreras said he is open to bringing NABJ and NAHJ back into some type of partnership, but he says it will take time for everyone to be ready to consider such a move.

“It’s more of discussions and challenges of what’s the next step forward…all of us are being very strategic and if we [were to] make a partnership we want to do it right this time,” Contreras says.

While the collaboration of NABJ and NAHJ seems like a perfect opportunity to revisit the possibility of a formal partnership between affinity groups, some are wary of the practicality of getting the groups back together.

“To start a new organization that brings together like-kind journalism organizations is something that is not looked on favorably,” mostly for fear of history repeating itself, says Balta, who initiated the idea of a joint conference with then-NABJ president Bob Butler, a freelance reporter. “I think what is much more plausible is for the individual journalism organization to have the flexibility of exploring joint conferences.”

It’s a good start.

Carlett Spike is a freelance writer and former CJR Delacorte Fellow. Follow her on Twitter @CarlettSpike.