Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Presidential debate moderators often go into hiding as they prepare to carry out their thankless jobs. But Fox News’ Chris Wallace caused a stir last week when he said in an interview that “it’s not my job” to fact-check candidates when he hosts the final 2016 presidential debate. The comments have drawn near-universal condemnation from journalists, and the backlash only crescendoed when NBC’s Matt Lauer allowed Donald Trump to lie about his opposition to interventions in Iraq and Libya with no follow-ups during a candidate forum last week.

Lauer was conducting a one-on-one interview, so there’s no obvious explanation for his failure. But Wallace’s comments resurrected a major philosophical question that has dogged the debate process since moderators took center stage as questioners beginning in 1996. Hands-off moderators such as Jim Lehrer have largely played the role of traffic cop in past elections, though the trend line points toward incrementally more direct confrontation with nominees. The candidacy of Trump has led many in the industry to call for additional involvement from the only non-candidates on stage.

There’s certainly a need for more probing questions and follow-ups by moderators, particularly with a candidate as inexperienced and unprepared as Trump. But on the narrower task of fact-checking, asking moderators to make the myriad instantaneous editorial decisions about when and how to jump in is an incredibly heavy burden, and they might not be best suited for it.

Trump’s Iraq War assertion is the easiest example of a disprovable statement—in a debate, Hillary Clinton can and should bat it down. But he has few other stated policy positions that can be fact-checked in the traditional sense. His more reprehensible traits, including racism, sexism, and penchant for conspiracy theories, often come in the form of innuendo that’s by nature more difficult to refute. And this is to say nothing of the real-time task of weighing fact-checks between Clinton–a candidate who’s traditional in both her policies and her relationship to the truth–and Trump, who many argue poses a potential danger to democratic institutions.

“There is a journalistic component to what the moderator does. But there’s so little time—that’s the problem—and that time really belongs to the candidates,” says Alan Schroeder, a Northeastern University journalism professor and presidential debate historian. “I’d rather trust PolitiFact or The Washington Post, which have done their homework and written [fact-checks] in a nuanced way, than rely on a moderator making a decision in real-time.”

Indeed, the pros at PolitiFact will have about 10 staff on hand during debates, says Editor Angie Drobnic Holan. The fact-checking organization has analyzed many of the campaigns’ most familiar claims already, so it will largely be reframing and resharing those on social media when the candidates take the stage.

“Fact-checking in real-time is incredibly hard—you really need to know the material,” Holan says, adding that PolitiFact’s traffic has skyrocketed this year. “I think the fastest we’ve ever gotten a full fact-check up is 20 minutes, and that’s when we already know the material beforehand. One or two hours would be pretty fast.”

The growth of such efforts at many news organizations does change the debate-night experience, particularly given the increase in multiscreen viewing. But there are also downsides. For one, the audience for live fact-checks isn’t necessarily the same one that watches a TV debate. And as I wrote in 2014, even political reporters watching from afar have a difficult time of correcting misinformation as fast as politicians can spew it.

It’s no surprise that the controversy over this topic has exploded at the tail end of the 2016 campaign. Critics have for years argued that asymmetric political polarization—that Republicans are on balance more extreme than Democrats—short-circuits journalists’ need for the appearance of objectivity. It’s a compelling argument that Trump has essentially proven with both extremist beliefs and a blatant disregard for the truth. He seems to have rendered journalists impotent, which no doubt helped fuel the outrage over Wallace’s remarks.

But whether debates are the most effective forum to shift this paradigm remains an open question. Stuart Stevens, Romney’s former campaign manager and an outspoken Trump critic, argues that there’s a clear difference between the role of moderator, like Wallace on Oct. 26, and that of interviewer, like Wallace on Fox News Sunday.

“It should be up to candidates to correct other candidates,” Stevens tells me in an interview. “That’s the whole point of this. It’s not a Sunday show.”

The journalist in me doth protest at this in the age of Trump. “I’m with you, brother,” Stevens replies. “I think Donald Trump is a disaster. But it’s up to Hillary Clinton to point that out in that moment. There’s no way to [fact-check] consistently and fairly.”

Neither option is fully satisfying, unfortunately. In 2012, for example, Mitt Romney was taking Stevens’s advice and attempting his own fact-check of President Barack Obama’s early description of the attack on a US consulate in Benghazi, Libya, as “an act of terror.” Obama had indeed called it that—albeit in a roundabout way—but the administration’s full public response was wishy washy at best.

When CNN’s Candy Crowley jumped in, she said that the president was technically right but awkwardly added that Romney was correct on the broader point. The interjection only added confusion to the exchange, making the moderator the story. Republicans like Stevens still groan at the episode.

“When the moderator starts playing that kind of role, its not a debate,” says Anita Dunn, former communications director for the Obama White House, speaking generally. “It’s a joint news appearance. And then the moderator in the debate opens himself or herself to looking like they are partisan.”

Of course, major news organizations have already bombarded Trump with more openly antagonistic coverage than any other candidate in recent memory—to no avail. It’s unclear whether radically altering debate norms will help or hurt the media’s broader credibility in holding Trump accountable.

In a series of focus groups conducted for a bipartisan working group on debates Dunn co-chaired at the Annenberg Public Policy Center last year, the main complaint from respondents across age groups was that moderators “tend to take sides, giving one of the candidates the edge.” Trump, an outlier, poses a particular quandary in this regard in 2016. But there’s no good answer to it. The Commission on Presidential Debates could choose an outsider to moderate the contests who will challenge Trump more directly; Trump could back out. Which is better for the public?

“The penalty for someone to walk away from the debates is not going to be that high unless the debates become more relevant,” Dunn says, citing a proportional decline in viewership among the voting-age population over the years. “And this is intertwined irrevocably to the moderator.”

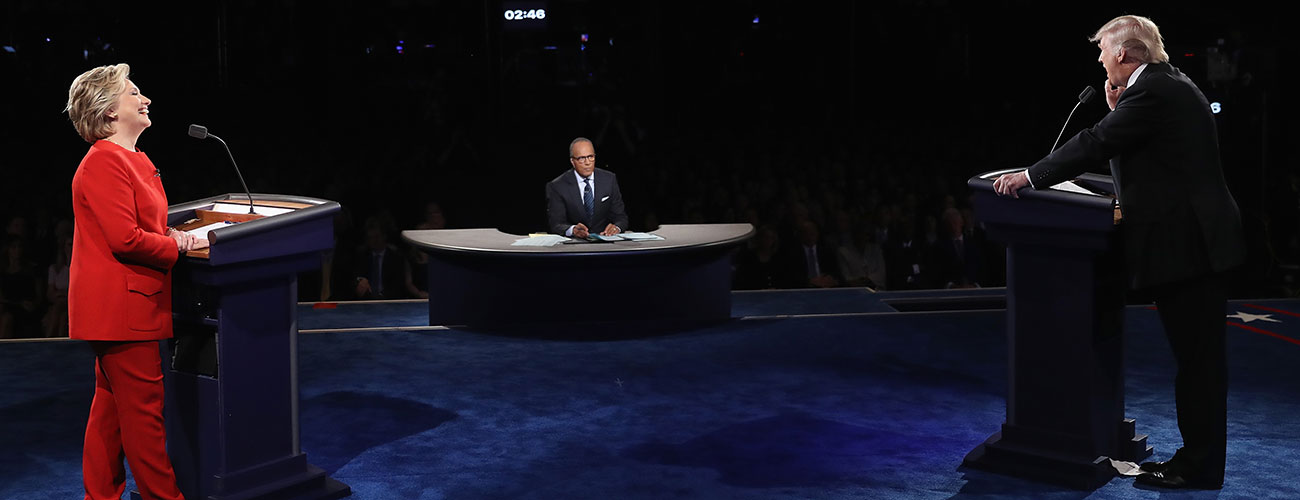

If the highly-rated primary debates are any indication, the general election contests will likely reverse that long-term trend. Moderators for the two other presidential debates include NBC’s Lester Holt, on Sept. 26, and CNN’s Anderson Cooper and ABC’s Martha Raddatz, on Oct. 9. Raddatz’s performance in a debate between vice presidential candidates in 2012 was rated highly by journalists and political operatives alike. It meanwhile seems dubious that Wallace will go as easy on Trump as many liberals fear. He grilled the eventual GOP nominee during the primary debates, using on-screen graphics to great effect.

There might something of a lesson there. Schroeder, author of Presidential Debates: Risky Business on the Campaign Trail, advocates for moderators to facilitate fact-checking in a more indirect way. If Trump claims, for example, that he didn’t propose a deportation task force to forcibly remove unauthorized immigrants, the moderator could alert the audience that the issue has been thoroughly fact-checked at a news site listed at the bottom of the screen.

“It wouldn’t take that much time, the moderator is not seen as taking sides, and yet they’re acknowledging that there’s a different reality [than what the candidate is suggesting],” Schroeder says. “The truth is that all of this fact-checking at a very thorough level by journalists is going to be better than what a live moderator can do off the top of his head.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.