Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

In 2023, a group including the MacArthur and Knight foundations announced Press Forward, a massive philanthropic effort to respond to the democracy-threatening collapse of local news. Press Forward committed funds amounting to an average of $100 million per year over five years to support local news. But in a single day earlier this month, five times that amount—$535 million per year—vanished from the media system when Congress, at President Trump’s directive, eliminated the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB). It was a crushing blow to the effort to revive community journalism.

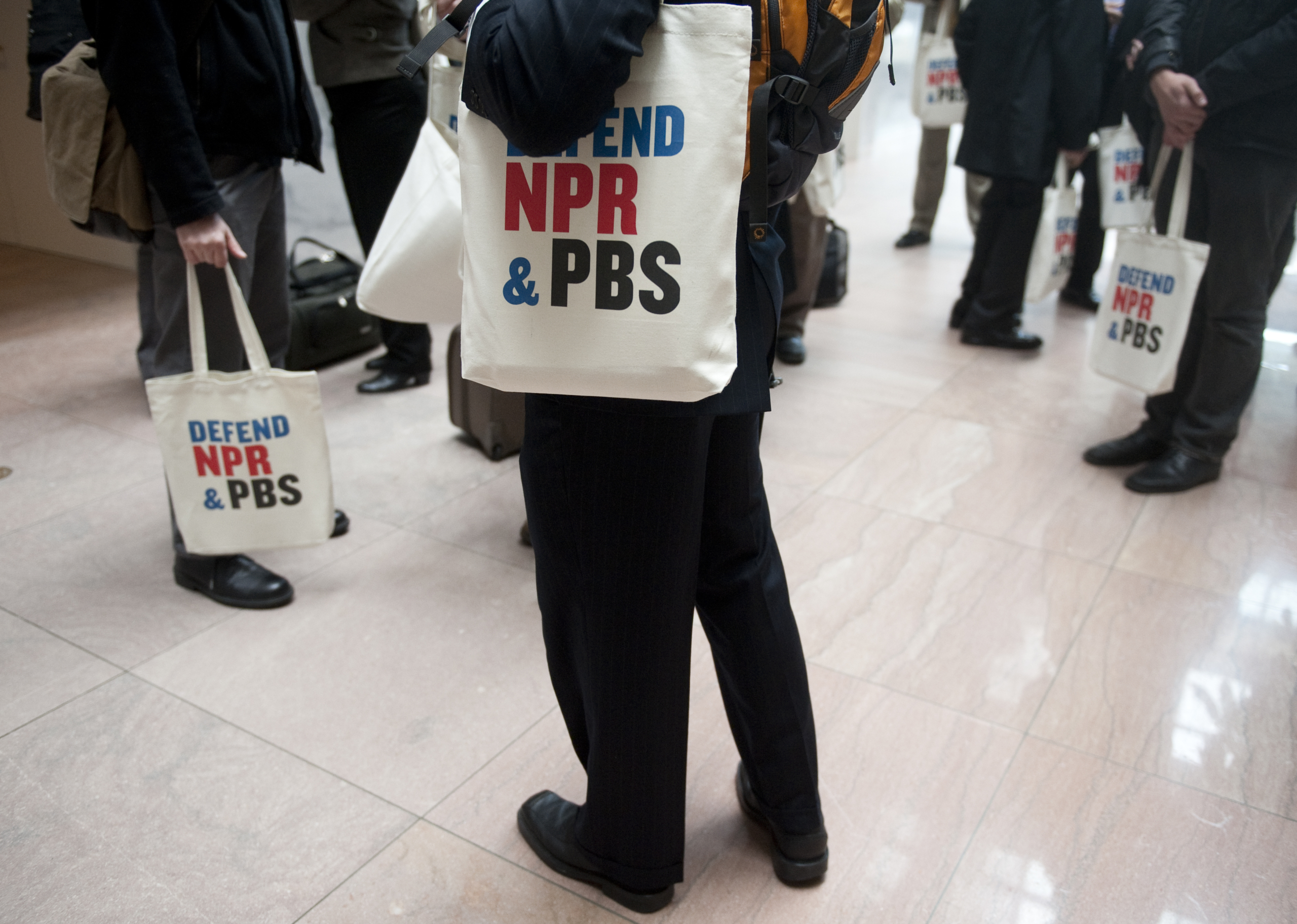

In response, Knight, MacArthur, and several other foundations announced this week that they were funding a Public Media Bridge Fund to fill the absence of CPB. About a hundred TV and radio stations were receiving more than 30 percent of their revenue from CPB; many of those would be in danger of going dark. Managed by the Public Media Company, the Public Media Bridge Fund aims to provide as much as $100 million, with $26.5 million raised so far, toward ensuring that those most at-risk stations survive.

The name of the fund raises a question: A bridge to what? Going forward, what is the proper role of taxpayer support for the media? The demise of CPB opens the opportunity to creatively rethink how funding for public broadcasting and other local media can work.

While the kind of content on public broadcasting has changed over time, it has always maintained the meta-mission of providing civic-minded programming that the public would not get from the commercial sector. In other words, public media addressed a failure of the market. The first question we should ask, then, is: What is the most important market failure now? I would argue that the collapse of local news is the media’s biggest problem. Since 2002, the number of local journalists has dropped 75 percent. More than a thousand counties across the country lack even one full-time journalist. This loss of community news is leading to corruption, misinformation, and polarization. Timothy Snyder, a Yale historian who studies tyranny, calls this local news crisis “the essential problem of our republic.” Luckily, it’s a problem that can be solved with public money.

Public broadcasting, especially radio, is a major source of local news. Of 1,400 public TV and radio stations, about 608 cover local news, according to the State of Local News report in 2020. That’s despite the fact that CPB required 75 percent of its funds to go to television, which does minimal local reporting. Radio is much better for that.

Some public radio stations are way ahead of the rest of the industry in their understanding of local business models. They mastered “membership” models long before small donors became a hot topic at local journalism conferences. What’s more, they’ve built an enduring physical architecture of powerful towers and “repeater” transmitters in low-population areas that reach parts of the country underserved by the internet. Several newspapers, including the Chicago Sun-Times and Lancaster Online, have even merged with public radio stations.

Public radio still has a long way to go to meet its potential as a solution to the local news crisis. More than half of the public stations in the US don’t do local coverage at all. Many of those that do focus only on broadcast pieces, failing to offer meaningful digital services. Too many have resisted collaborations with websites and newspapers. But they are well positioned to play a key role if they adapt.

But broadcast TV and radio should not be the only type of nonprofit media that is funded. Why should content that swims through the airwaves be subsidized, but an article on a nonprofit local news website should not? There are four hundred local nonprofit websites directly covering communities. It’s time for public policy to recognize the existence of the internet.

The focus should be on publicly financed media, not only public media that is overseen by a government agency. Let’s stop thinking that publicly supported media can only mean a fund like CPB that gives out grants. What matters is that taxpayers are willing to support the services, whatever the form.

Illinois, for instance, has a pilot program to provide refundable tax credits for newsrooms that hire or retain local reporters, including in public radio. About $4 million supports 120 local news outlets. It’s a nonbureaucratic, content-neutral system. A national version on the financial scale of CPB would support 20,000 community reporters.

In Kansas, the legislature is considering a tax credit for small businesses that advertise with both commercial and noncommercial local news. In New Mexico, California, and Washington State, taxpayers subsidize fellowships for professional journalists placed in local newsrooms. In New York City, a share of the government’s advertising is targeted toward community media.

This is all publicly financed media.

Let’s push this one step further. Might for-profit local news outlets also receive public funding? Journalism that holds the government accountable, provides crucial information to residents, and helps a community accrue the civic capital to solve its own problems is a public good, whether it’s delivered by a for-profit or nonprofit outlet.

Giving taxpayer and philanthropic support to for-profit companies has not been part of the historical philosophy of public broadcasting. But other government social programs have taken a different approach. For example, students are allowed to use Pell Grants and Guaranteed Student Loans to go to private colleges. And commercial farmers receive $30 billion per year to advance public goals related to sustaining the food supply. When taxpayer dollars go to commercial companies, policy needs to provide incentives and guardrails. Illinois’s tax credit for retaining local reporters encourages companies to add reporters for more money; if reporters get cut, the companies get less.

The inclusion of for-profit outlets might also broaden political support for public media. The erosion of trust in the media results mostly from disingenuous attacks, not bias or journalistic sloppiness. But crafting a publicly financed system that is big enough to truly address the local news crisis requires the embrace of a wide range of voters who view funding as neutral.

Before public broadcasting came along, there was a larger and more enduring government intervention in local news. That was a massive subsidy to the fledgling newspaper industry in the form of artificially cheap postage rates. This subsidy lasted for more than a hundred years. At its peak, it provided financial support that would be the equivalent today of about $50 billion per year, far bigger than CPB. What would be equivalent policies for the modern era?

Here’s another idea: a tax credit or voucher for every American to help them purchase a subscription or give a donation to a local news outlet of their choosing. Each resident would decide where the support goes—with public radio and television among the options—as long as the outlet provides professional journalistic coverage. In this model, the government would amplify the consumer’s spending power, like it does with tax-deductible deductions for donating to charity.

Approaches like this would generate greater political support—and more dollars. According to my calculations with Rebuild Local News, an organization to develop public policies to strengthen local news, media needs $1 billion to $2 billion a year in taxpayer support, from some combination of state and federal governments, for local news; we’re not going to get there with niche programs that appeal to narrow slivers of the political spectrum.

This prompts me toward a heretical thought: What if the best way to help the media is not with carefully sculpted grants provided to worthy programs by a panel of wise people, but rather big, messy, blunt-instrument policies that push far more dollars into the system and lift all boats?

The 1967 Carnegie Commission that created the institution of public media made one proposal that was tragically ignored. Rather than forcing leaders to go before Congress each year to beg for funds—which the commission presciently viewed as subject to future political machinations—they suggested the system be financed by levying an excise tax on TV sets, starting at two cents and rising to five cents. (That’s the equivalent of about fifty cents today.) That money would be deposited in a trust fund for use by CPB. Congress rejected the idea and opted instead for a system of regular appropriations.

But the Carnegie Commission had the right idea. A tiny fee on the technology that brings us information in the modern system would solve many problems. The tax might be tied to internet advertising, the sale of mobile phones, or data-extracting AI. This system would generate funds to make CPB seem puny.

Making Big Tech pay up for publicly financed media is appropriate, since these companies played a significant role in undermining the original business model for local news. The rise of AI, too, is likely to exacerbate the local news crisis. That calls to mind what President Lyndon Johnson said in signing the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967: “Miracles in communications are our daily routine.… Today our problem is not making miracles—but managing miracles. We might well ponder a different question: What hath man wrought—and how will man use his inventions?”

In 2025, we are at another critical juncture. The solution is not going to be a big federal fund or a replica of CPB. At the same time, public support for local media is more important than ever. Journalists will need to figure out how to adapt to the new technological and political realities to create something bigger, bolder, and more enduring.

This article has been updated.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.