A cache of 759 files leaked by WikiLeaks to ten news partners—and subsequently leaked to three non-partner outlets—is the fourth and smallest classified document dump to ruffle the Obama administration since the release of the Afghanistan war logs in July of last year.

The “Guantánamo files,” as they are being called by news organizations now reporting on them, are believed to be from the same tranche of documents allegedly obtained by Private Bradley Manning, from which WikiLeaks released its Afghan and Iraqi war logs and its collection of U.S. embassy cables. The files are said to contain some 750 intelligence summaries, or Detainee Assessment Briefs, that The Washington Post—a newly included WikiLeaks partner—says are “intelligence assessments of nearly every one of the 779 individuals who have been held at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, since 2002.” (There are currently 172 prisoners at the facility.)

The documents are an average of two to twelve pages in length and were written by the Defense Department between 2002 and 2009; they are marked “Secret” and “Noforn,” meaning they are not to be shown to non-U.S. citizens. Kevin Gosztola at FiredogLake has a good breakdown of what you can actually expect to find in a “Guantánamo file.”

The News Partners

In this latest round of leaks, WikiLeaks lists as its news partners The Washington Post, The McClatchy Company, Spanish newspaper El Pais, Britain’s The Daily Telegraph, Germany’s Der Speigel, France’s Le Monde, the daily Swedish tabloid Aftonbladet, Italy’s La Repubblica and the weekly newsmagazine L’espresso, and British journalist Andy Worthingon, who has written extensively on Guantánamo and Bagram.

Instantly noteworthy: While WikiLeaks regulars Der Speigel, Le Monde, and El Pais are still in the loop, The New York Times has once again been cut out—and for the first time, The Guardian too has been ignored by Assange’s organization. However, both papers have still managed to produce substantial packages—perhaps the most substantial of any published overnight—on the Guantánamo files.

The reason is that the Times was given access to the files by an unnamed source. In its Guantánamo package today, the Times notes: “These articles are based on a huge trove of secret documents leaked last year to the anti-secrecy organization WikiLeaks and made available to The New York Times by another source on the condition of anonymity.” The Times then shared the documents with The Guardian and NPR.

At the website journalism.co.uk, Guardian investigations editor David Leigh said the reason his paper and the Times had been cut out was because “of Julian Assange’s feuding with the Guardian and the New York Times” and that he was now going elsewhere. On the Guardian’s live blog, Leigh writes:

Last year, the Guardian brokered a pioneering deal with Assange under which some of these packages, notably 250,000 leaked US diplomatic cables, would be published collaboratively across the world. The original partners were the New York Times and other European papers, such as El Pais in Spain.

But Assange objected to some articles the Guardian and the New York Times had written, notably those detailing the Swedish sex allegations over which he is currently fighting extradition. He decided to tear up the original deal. According to those close to him, he conceived a plan instead to distribute the Guantánamo material only to a range of rival papers, including the right-wing Daily Telegraph, the Washington Post and Al Jazeera, whilst preventing readers of the Guardian and the New York Times from having access to it.

According to McClatchy, partner outlets were given the documents last month on an embargoed basis to allow them time to report on them and put together their packages. Then, Sunday night, WikiLeaks “abruptly” lifted the embargo after it learned the Times and Guardian had gotten hold of the files and were poised to publish stories on them.

Writing last night, The Nation’s Greg Mitchell asked “Who leaked the WikiLeaks files to The Times?” Then Mitchell tries to tease out whether the last-minute embargo break by WikiLeaks led to early publication on the Guantánamo files, or whether a decision to go early from the Times caused the WikiLeaks to lift its embargo.

Who leaked the WikiLeaks files to The Times? To summarize: WikiLeaks gave its Gitmo files to 7 news outlets but not the NYT or The Guardian, probably due to falling out with them over previous leaks. But someone leaked the files to the Times, which in turn gave them to The Guardian and NPR. The Times decided to go ahead tonight with covering / publishing files tonight, and WikiLeaks and partners apparently then rushed to lift embargo and come out with their coverage an hour or two behind the Times. At least that’s all suggested by McClatchy and The Guardian. Or did NYTlearn that embarge was about to be broken and so moved “abruptly” first?

In any case: WHO LEAKED THE FILES TO THE TIMES?

Remember, the Times is not claiming that it got them from a government or Gitmo or military source, or from the original leaker — it says these ARE the WikiLeaks documents. So does that mean they came from one of several disgruntled ex-WikiLeakers?

We will have to wait and see.

The Reports

The Washington Post, taking its first swing at a WikiLeaks dump as an official WikiLeaks partner, offers a report by Peter Finn that focuses on revelations within the documents about the movements of Al Qaeda operatives in the aftermath of 9/11. The piece is a catalogue of escapes and movements and tracks Bin Laden in the months immediately following the WTC attacks.

Bin Laden, accompanied by Zawahiri and a handful of close associates in his security detail, escaped to his cave complex in Tora Bora in November. Around Nov. 25, he was seen giving a speech to the leaders and fighters at the complex.

He told them to “remain strong in their commitment to fight, to obey the leaders, to help the Taliban, and that it was a grave mistake and taboo to leave before the fight was completed.”

According to the documents, bin Laden and his deputy escaped from Tora Bora in mid-December 2001. At the time, the al-Qaeda leader was apparently so strapped for cash that he borrowed $7,000 from one of his protectors—a sum he paid back within a year.

Finn’s is a well-synthesized and intriguing report, and an accompanying interactive database of prisoners past and present, produced before the leaks and linking to “Status Review Tribunal Transcripts” for some of the detainees, is informative and easy to use. But compared to some other coverage it feels slight. This may be the result of the suddenly lifted embargo, and we should expect more to come.

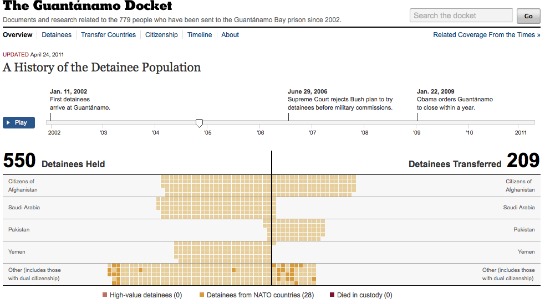

The New York Times has a more robust package that includes a wonderful interactive, “The Guantanamo Docket,” which shows the number of detainees held and transferred at any given time between January 2002 and 2011. The numbers are broken down by nationality (Afghani, Saudi Arabian, Pakistani, Yemeni, and other) and, when you press play on the Docket’s timeline, you can see how many detainees of each nationality are held and released as time goes by. Here’s a screenshot:

Click on the dots and you learn the name, status, and citizenship of the prisoner it represents.

The reports on this latest leak also seem more muscular and more critical from the Times than they had been for some of the previous WikiLeaks dumps. One report, “Lives in An American Limbo,” notes that “the leaked files show why, by laying bare the patchwork and contradictory evidence that in many cases would never have stood up in a criminal court or a military tribunal.” Among a list of findings in the same report are examples of extreme interrogations—on which there is little said in the documents—as well as cases of seeming innocents being declared “enemy combatants” against available evidence, and this report on an Al Jazeera journalist held in captivity at Gitmo.

A journalist’s interrogation: The documents show that a major reason a Sudanese cameraman for Al Jazeera, Sami al-Hajj, was held at Guantánamo for six years was for questioning about the television network’s “training program, telecommunications equipment, and newsgathering operations in Chechnya, Kosovo, and Afghanistan,” including contacts with terrorist groups. While Mr. Hajj insisted he was just a journalist, his file says he helped Islamic extremist groups courier money and obtain Stinger missiles and cites the United Arab Emirates’ claim that he was a Qaeda member. He was released in 2008 and returned to work for Al Jazeera.

The Times says in this same report that “The documents can be mined for evidence supporting beliefs across the political spectrum about the relative perils posed by the detainees and whether the government’s system of holding most without trials is justified.” But it is clear by the time we arrive to the story’s last two paragraphs that the Times is holding firmly to its established anti-Gitmo stance.

…an assessment of a former top Taliban official said he “appears to be resentful of being apprehended while he claimed he was working for the US and Coalition forces to find Mullah Omar,” a reference to Mullah Muhammad Omar, the Taliban chief who is in hiding.

But whatever the truth about the detainee’s role before his capture in 2002, it is receding into the past. So, presumably, is the value of whatever information he possesses. Still, his jailers have continued to press him for answers. His assessment of January 2008 — six years after he arrived in Cuba — contended that it was worthwhile to continue to interrogate him, in part because he might know about Mullah Omar’s “possible whereabouts.”

Also worth checking out at the Times is Charles Savage’s similarly damning report, “As Acts of War or Despair, Suicides Rattle a Prison.”

The Guardian is strong once again in handling the latest WikiLeaks material, and its angry tone as strong as ever. Opening its central Guantánamo files story, David Leigh, James Ball, Ian Cobain, and Jason Burke write:

The US military dossiers, obtained by the New York Times and the Guardian, reveal how, alongside the so-called “worst of the worst”, many prisoners were flown to the Guantánamo cages and held captive for years on the flimsiest grounds, or on the basis of lurid confessions extracted by maltreatment.

Then there’s this interview with Reprieve founder Clive Stafford Smith.

But just as effective as the vigor and anger with which the Guardian once again presents its WikiLeaks reporting are the angles and the focuses of its reporting. Particularly striking is James Ball’s use of the files to flesh out previous reporting on the mental health statuses of many of Gitmo’s detainees. From his his report, “Grim toll on mental health of prisoners”:

A 2004 assessment of Algerian Abdul Raham Houari noted that owing to “significant penetrating head trauma in 2001” he had frontal brain damage causing psychosis, slowed motor functions and difficulty with speech and understanding.

The assessment said he would need some form of custodial long-term care. Houari was held in Guantánamo for a further four years, during which time he made at least four suicide attempts, according to press reports.

…None of the five detainees believed to have killed themselves at Guantánamo Bay have any mental health issues noted within the files. However, all have a record of alleged disruptive behaviour and non-compliance. Most are among the 25 detainees who the files say went on hunger strikes.

Yasser Talal Zahrani, one of three prisoners who killed themselves on 10 June 2006, was noted to be of low intelligence value with “unremarkable” exposure to jihadist elements.

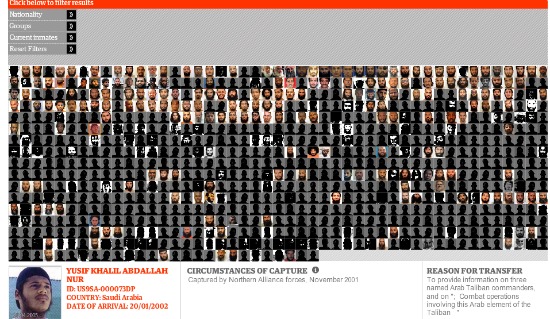

The Guardian’s Chris Fenn, Simon Jeffery, Ami Sedghi, and Sean Clarke also offer a typically impressive interactive that features clickable images (some are blacked out silhouettes) of all 779 detainees that have been captured and transferred to Gitmo. When you click a picture, you discover the detainee’s name, ID number, nationality, date of arrival at Guantánamo, the circumstances of his capture, and reason for transfer. The information is derived from the newly leaked files.

Interestingly, McClatchy’s reporting on the WikiLeaks Guantánamo files is Guardian-esque in its strong wording and tough take on what it views as incompetence at the prison. McClatchy’s story is a catalog of blunders, from “intelligence analysts” who are “at odds” over who to trust, to the repatriation of valuable sources. Carol Rosenberg and Tom Lasseter write: “Viewed as a whole, the secret intelligence summaries help explain why in May 2009 President Barack Obama, after ordering his own review of wartime intelligence, called America’s experiment at Guantanamo ‘quite simply a mess.’”

Elsewhere, the more right-of-center Telegraph, a newcomer to the WikiLeaks fold, has a single report that, while noting the dubious nature of some detainees’ imprisonments and the controversial techniques used to obtain information, focuses more than any other English-language report on the kinds of frightening terrorist plots that the files contain. From the report by Christopher Hope, Robert Winnett, Holly Watt, and Heidi Blake:

*A senior Al-Qaeda commander claimed that the terrorist group has hidden a nuclear bomb in Europe which will be detonated if Bin-Laden is ever caught or assassinated. The US authorities uncovered numerous attempts by Al-Qaeda to obtain nuclear materials and fear that terrorists have already bought uranium. Sheikh Mohammed told interrogators that Al-Qaeda would unleash a “nuclear hellstorm”.

*The 20th 9/11 hijacker, who did not ultimately travel to America and take part in the atrocity, has revealed that Al-Qaeda was seeking to recruit ground-staff at Heathrow amid several plots targeting the world’s busiest airport. Terrorists also plotted major chemical and biological attacks against this country.

NPR similarly sounds the alarms, though not by detailing terror plots that never were. Instead, NPR offers a detailed piece on detainees that were transferred despite being labeled “high risk,” and also provides an interactive of detainees who had reengaged with terrorism.

A quick and early assessment seems to suggest that the newer English-language WikiLeaks partners, with the exception of McClatchy, have taken a less critical view of the U.S. than the Times and the Guardian have. It is those two papers, now out in the cold, whose views appear to be more in sync with some of the pronouncements of the WikiLeaks front man who put them there. It will be interesting to see how new partners’ coverage will take shape as more of their reporting is published.

Joel Meares is a former CJR assistant editor.