Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

“Food is a topic which is like that little string on the sweater,” Pablo De La Rosa, a journalist in South Texas, told me. “You pull it, and the whole thing starts coming undone. In terms of understanding the culture, the history of the region, it’s that kind of thread.” The Rio Grande Valley, where he lives, stretches five thousand square miles. Sugarcane, grapefruit, sorghum, cotton, and maize grow there, tended by thousands of agricultural workers. Recently, when the federal government shutdown ripped away SNAP benefits, De La Rosa had in mind the more than three hundred thousand local people reliant on the program. His resulting article, “They Grow the Food. So Why Are So Many Going Hungry?,” appeared in the Border Chronicle, which aims to cover the land spanning from San Diego and Tijuana to Brownsville and Matamoros.

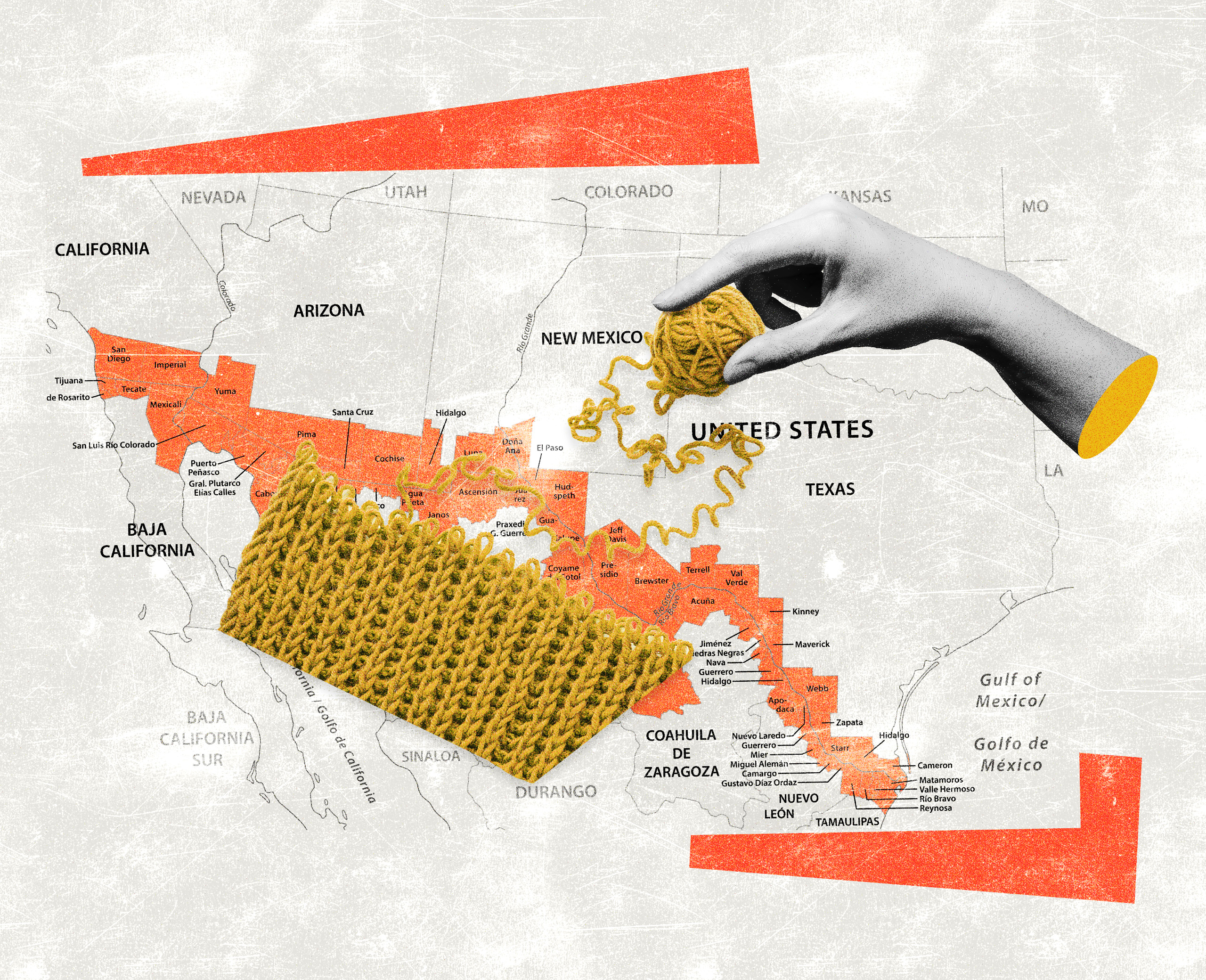

The Border Chronicle was started in 2021 by a pair of journalists—Melissa del Bosque, who has won an Emmy, a National Magazine Award, an RFK Human Rights Journalism Award, and the Hillman Prize for border-related reporting, and Todd Miller, who has also long written about the border, with a particular interest in climate change, border patrol, and corporate power. The idea was to counter perceptions from the outside: “The way of thinking in the national debate is that there’s nobody at the border,” as del Bosque told me. “It’s this sort of barren place, or it’s this place that’s under some sort of threat or ‘invasion.’” The Chronicle works, she said, “from the perspective of people actually living in these communities.” In practice, “we don’t do much breaking news,” she said. “What we like to do is explain not just the what’s happening, but the why and how.” The publication’s main mission is to push against what she calls “border theater”—the use of the United States–Mexico border as, in del Bosque’s words, “the backdrop for national politics and rhetoric.”

When del Bosque and Miller started the Border Chronicle, it was from Tucson, where they both live, at del Bosque’s house, where she held a meeting with colleagues. “We talked about, you know, what can we do?” she remembered. “Media is kind of falling apart. We want better coverage on the border. And, you know, I got this idea. We need a region-wide publication so that we can have these conversations, so that people in border communities can talk about what is affecting them, and hopefully it will seep into the national narrative, so they’ll start seeing the border as more dimensional, and not just this hellscape that has been painted by politicians.” Del Bosque applied to a local reporting fellowship from Substack and secured a hundred thousand dollars, plus some administrative support: with Miller quickly aboard, the Border Chronicle was off and running.

De La Rosa became a regular contributor—though everyone involved has or has had other jobs simultaneously: Miller is a teacher; del Bosque worked as an editor at Lighthouse Reports; De La Rosa freelances. In time, they have built up a readership of about twenty thousand subscribers, twelve hundred and fifty of whom are paying. The Border Chronicle hopes to become mostly reader-supported, though del Bosque told me that “there is no real working revenue model for journalism right now, so it can feel incredibly daunting, possibly even insane, to say you’re building a media outlet during this volatile and difficult period in our history.” In order to be sustainable in 2026, they need to have at least four thousand paid subscribers. In the meantime, they got a boost this month from the MacArthur Foundation, in the form of a three-hundred-and-fifty-thousand-dollar donation, which makes this a “pivotal moment,” del Bosque said. “Now I can work on this full-time.”

In January, the Border Chronicle plans to move from Substack to a new platform, Ghost. They are experimenting with podcasts and video, and recently featured an interview with Isabel Garcia, a longtime immigration rights activist and co-chair of the Coalicíon de Derechos Humanos, a group focused on, in their words, “increasing public awareness of the magnitude of human rights abuses, deaths and assaults at the border resulting from U.S. policy.” Migrants, said Garcia on the podcast, “gave me a meaning to life that, you know, carries me to this day, because really it is essentially their fight that clarifies any other right.”

Del Bosque also hopes to formalize De La Rosa’s position. One of his recent stories on the shutdown and SNAP weaved its way through the South Texas household of Josie Del Castillo, a figurative painter and lecturer at the University of Texas–Rio Grande Valley. Del Castillo is a single mom who makes about eleven hundred dollars per month; she has depended on SNAP. “Del Castillo began tightening her food budget last week, skipping more expensive cuts of meat and being more flexible about what she selects for her daughter and herself,” De La Rosa wrote. More fundamentally, as he wrote in the other piece on hunger in the RGV, “agriculture in the region is perceived not merely as a business, but as a question of justice, equity and belonging,” linking the history of agricultural workers’ movements in the area to present-day realities, as people growing nationally prized ruby red grapefruits and sweet onions are more often than not living in a food desert. They also might be the children or grandchildren of people who once marched nearly five hundred miles to the state capitol, agitating for better working conditions in the melon fields. In the lead-up to Thanksgiving, De La Rosa told me, the Food Bank RGV was “seeing many times more traffic than usual.”

“You know, the border deserves to have art. It deserves to have culture,” del Bosque said. “There’s this really impoverished narrative around what SNAP is or means for people.” And yet: “We have this whole authoritarian takeover where they’re just, like, you know, becoming richer and richer by the moment. Here’s a small amount of money that could allow this woman to, you know, continue to be an artist in her community and not have to leave.” De La Rosa told me that the story on Del Castillo began out of a sense of a “common thread” among SNAP recipients in the RGV community. “Many of us need these programs to even make it through school,” he said. “To make it past just a minimum wage job. Many of us are the first generation to escape that, and we need help to make it happen, even if some community members don’t want to see it or it makes people uncomfortable to talk about.”

De La Rosa sees writing for the Border Chronicle as a delicate act. “I’m trying to write for a national audience. I’m trying to write for a local audience. I’m trying to write for a local audience that’s educated about it. I’m also trying to write for an audience that may be just sort of waking up to it for the first time, even though they’ve lived here their whole life,” he told me. The Border Chronicle, he said, is “really it for a lot of people. It’s the mainstream space. It’s reality.”

Narrative and reality, to the Border Chronicle, are deeply linked: del Bosque noted the shooting at an El Paso Walmart in 2019, the deadliest attack on Latinx people in American history, and perpetrated by a man convinced of, in the words of his manifesto, a “Hispanic invasion.” As del Bosque told me, “This rhetoric and this political theater or border theater has very real consequences for people at the border and for people who are migrating through the border.” The border is used, she said, “by people who don’t live there, and for various reasons that have nothing to do with the people that live there, and often really does not benefit them at all. If anything, it creates a more dangerous environment.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.