Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

In our Winter 1965 issue, Daniel J. Leab, then CJR’s editorial assistant, compiled nearly 20 comic strips and frames that showed how the Cold War had come to the funny pages. The collection showed the anxiety and bellicosity of the age, and lead Leab to wonder if this widely read but little examined section of the newspaper harmfully shaped mass opinion.

“Gentlemen may cry. Peace! peace!—but there is no peace…” Patrick Henry’s cry of 1775 has become the theme of the “cold war comics” today.

What are cold war comics? In American newspapers, they are strips whose central characters at one time or another participate in the cold war, usually by fighting, at home or abroad, against one Communist menace or another. Some of these strips also serve as propaganda for the armed forces.

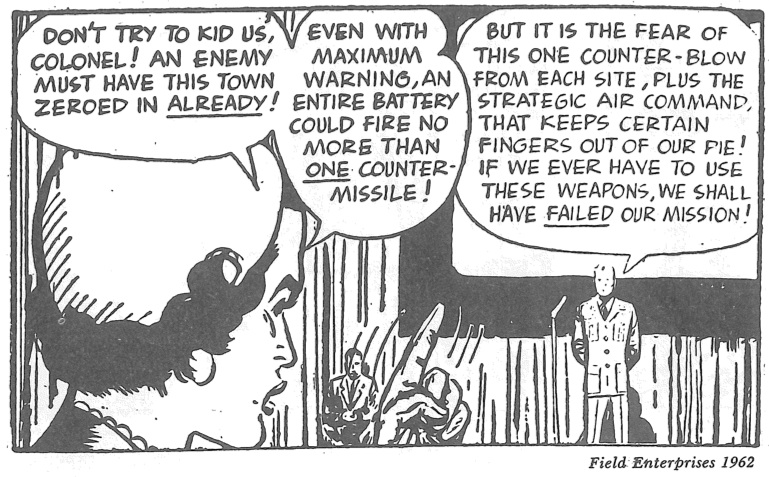

This does not mean that they are monolithic. In fact, on occasion, quite the contrary is true. Captain Easy has battled homegrown xenophobes who bombed schools and dynamited synagogues, while Steve Canyon, in the face of the aroused populace of an American town, has defended the right of peace marchers to demonstrate at an ICBM base.

Despite these individual instances, on the whole the cold war comics are defending and promoting an American point of view that is jingoistic, often highly belligerent, and meant to be taken seriously. The strips are usually extremely realistic in detail, no matter how far-fetched the plot. What could be more unbelievable than a storyline which has the father of Terry Lee‘s beloved turning up in the Soviet Union and blackmailing Nikita Khrushchev by claiming to have a copy of Stalin’s political testament? Yet the tale is made almost credible by panels which are Brueghel-like in their naturalistic detail of the Kremlin and its rulers.

Cold-war comics can be divided into two groups. One is those whose central characters are cold-war warriors, whether they be freelance like Johnny Hazard (a charter pilot) or members of the armed forces like Captain Dan Flagg, USMC. This group represents the survivors of the spate of action and adventure strips that flourished in the 1930’s and 1940’s. With a few exceptions these strips declined in the 1950’s. However, some of them found a new lease on life by hitching their plots to the cold war. Battling America’s enemies was nothing new for comic strip heroes, but whereas in the past (at least in peacetime) Don Winslow and Secret Agent X-9 and their contemporaries had fought the representatives of an “un-named foreign power,” now Smilin’ Jack and Buz Sawyer fight specific foes in the Communist world.

These foes are as up-to-date as the headlines of the newspapers in which the strip appears: Smilin’ Jack breaks up a ring of Cuban smugglers who had been bringing dope into the United States from behind the “castor oil curtain.” Buz Sawyer is instrumental in stopping a Zengakuran march against a U.S. naval base in Japan.

Even when the story lines move away from the cold war the illustrators still offer a high public-affairs content. Steve Canyon returns to Washington for reassignment and learns about the new space orientation of the Air Force; Captain Easy discusses the state of the American economy with his employer, the head of McKee industries; Terry Lee’s ward returns to the United States from Asia to obtain an education and is enrolled in the Air Force Academy.

It is not difficult to understand why the illustrators of the strips in this group, especially those whose central characters are enrolled in some branch of the armed forces, receive excellent cooperation from some of the personnel of government defense agencies.

The second group of cold-war comics differs from the first not in outlook but in presentation. Usually the situations in these strips, although often not remote from either violence or contemporary life, are removed from current political events. Yet occasionally a political point of view is eased into the surroundings that the illustrators have created. The insidiousness of this material is that a hardline view of the cold war becomes a part of everyday life in the comics.

Enough comic strips follow this line to make it worth noting. In attempting to circumvent red tape while hurrying to join Mary Perkins, her husband Pete Fletcher is detained by Communist guards for having illegally crossed the frontier. Subsequent events cause Mary to reflect that it is impossible “not [to] worry… with Pete interned… and he probably had his cameras… they’ve held people for years with less reason than that.” Kerry Drake, while on vacation in Florida, becomes involved with a group headed by a bearded, cigar-smoking individual dressed in GI fatigues who is planning a phony invasion of a Caribbean island in order to arouse anti-American feeling. The Saint finds that his competitors in a treasure hunt are Eastern European Communists who had once been ardent Nazis.

Comment in the comics about the American establishment and its domestic and international policies is not limited to these strips. Lil’ Abner, Pogo and their like are frequently as topical as any of the cold-war comics. But in toto they are not as consistently propagandistic; there is editorializing but not continuous sermonizing. B.C. may comment ironically, even acidly sometimes, about the foibles of our time, but there is no likelihood in that strip of a statement such as that by a character in Terry and the Pirates that “the only good Red is a dead Red.”

In the past many American comics have been bellicose, but rarely did they comment so recognizably on the international scene.

One must ask whether the cold-war comics, directed at the least sophisticated part of the audience, and offering glib solutions to world problems and caricatures of contemporary personalities both East and West, do not actually do harm. A newspaper presents itself as a reporter of fact; these comic strips are misrepresentations of actuality. The cold-war comics raise questions of journalistic responsibility for newspapers and their editors.

The illustrations were selected from a survey of six New York newspapers from 1957 through 1963.

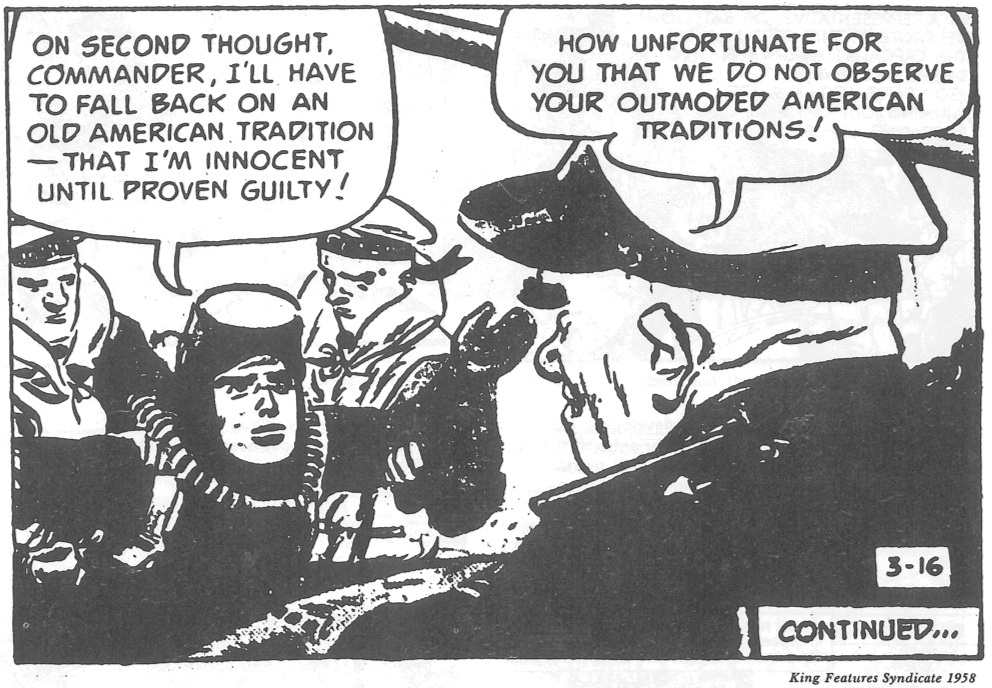

Johnny Hazard finds out about Soviet law from a Russian naval commander:

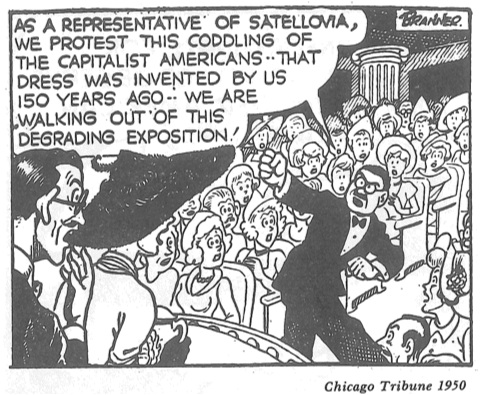

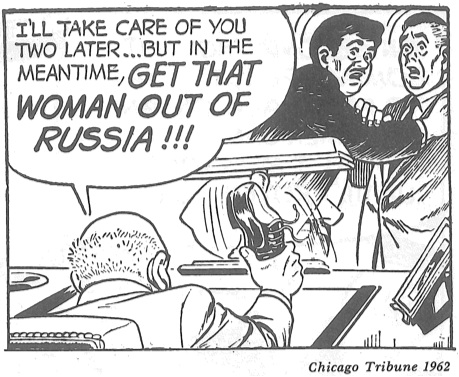

Winnie Winkle shows development of “actuality” in cold-war comics. When Winnie Winkle went to Paris in 1950, her antagonist was a fictional “Satellovian” whose actions resembled those of a Soviet delegate to the U.N. In 1962, she went to Moscow as part of a cultural exchange program and proved annoying to an unmistakably identified Kremlin ruler.

Winnie Winkle in Moscow, 1962:

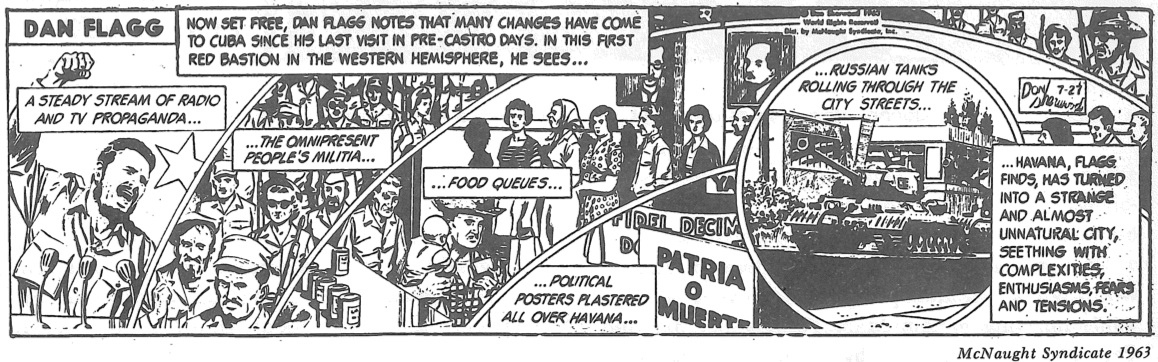

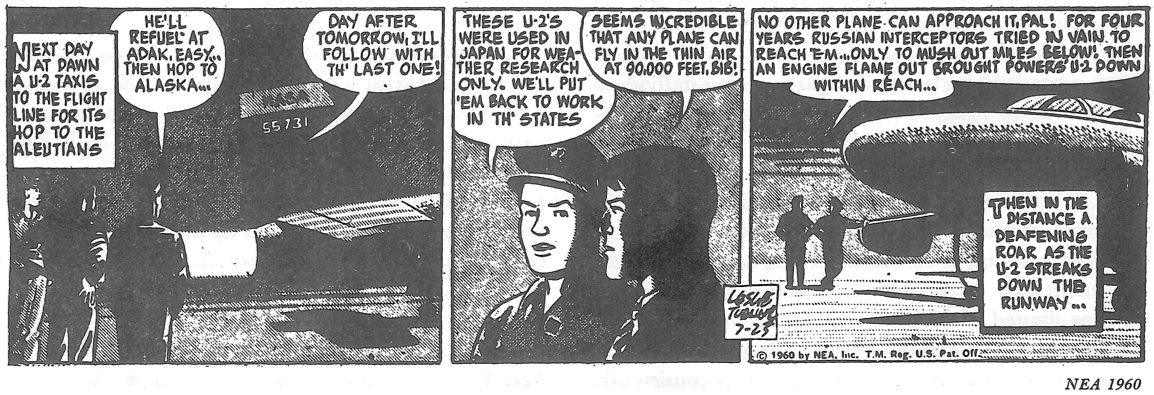

Cold-war comics comment freely on contemporary history. Dan Flagg reported the scene in Cuba; Captain Easy summarized the U-2 incident of 1960 within weeks.

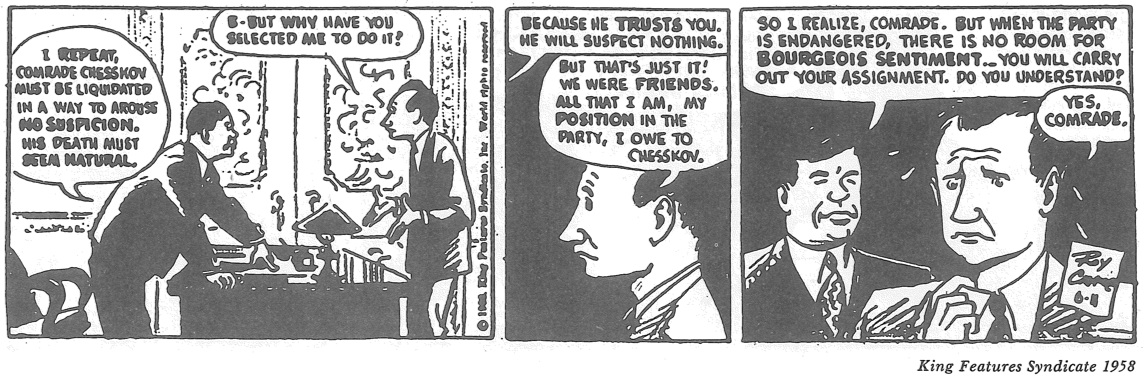

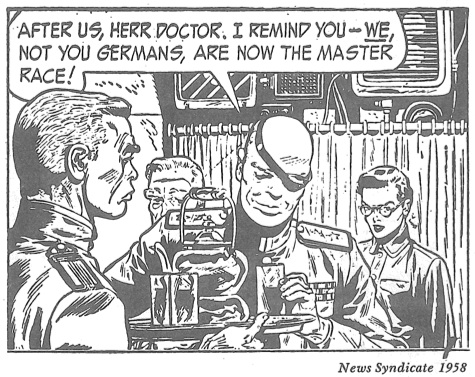

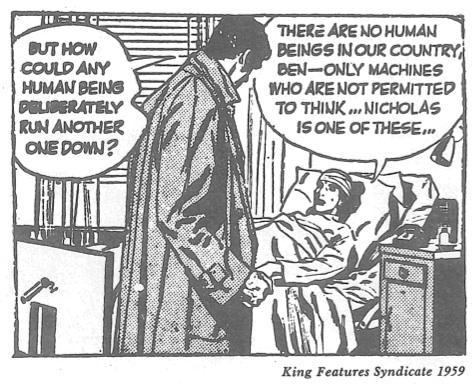

Comic strip readers meet “the enemy” as the artist sees him—unsentimental and cruel in Buz Sawyer; arrogant and inhuman in Terry and Big Ben Bolt:

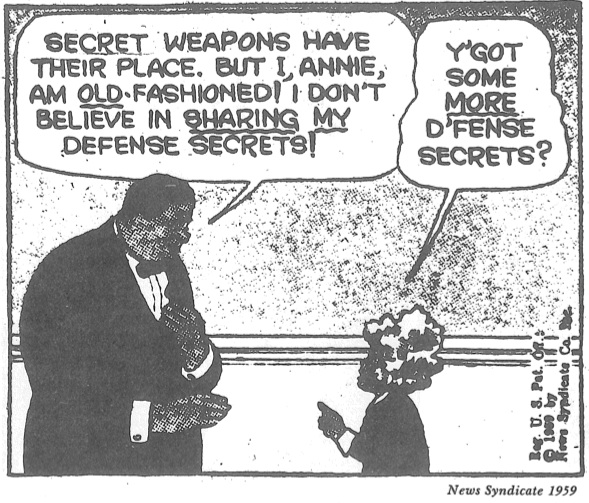

As always, Little Orphan Annie‘s kindly acquaintances leave no room for doubt about their views:

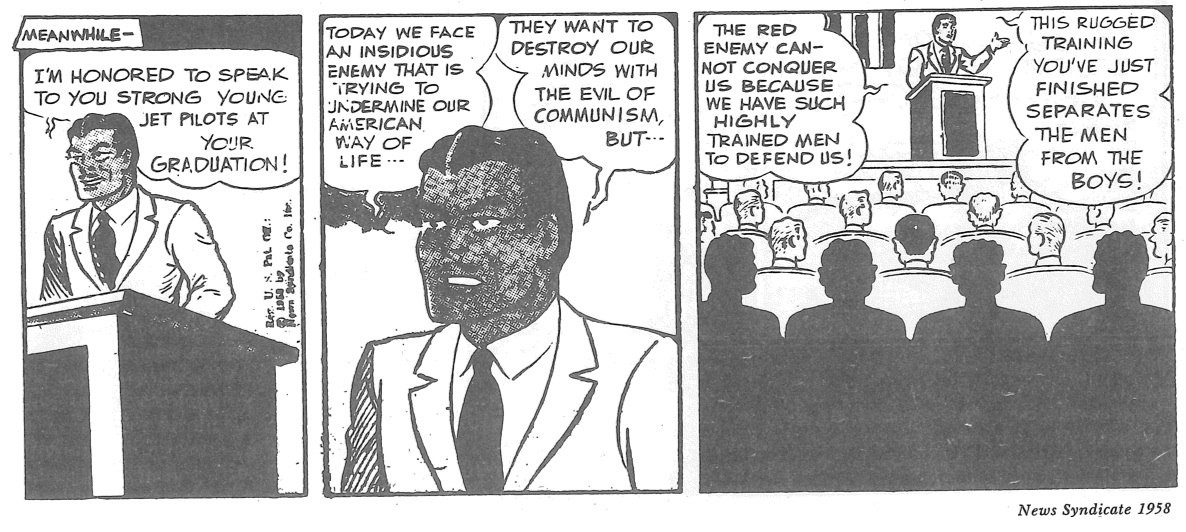

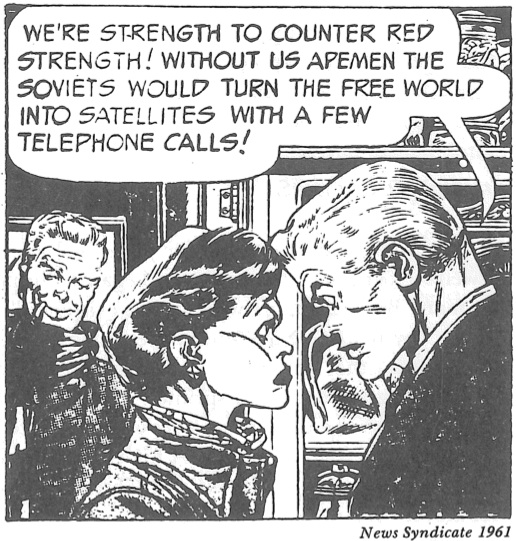

Characters in the cold-war comics are often placed on the platform by their creators and allowed to lecture the reader. Buz Sawyer, Steve Canyon, and Smilin’ Jack have become idea salesmen as well as heroes.

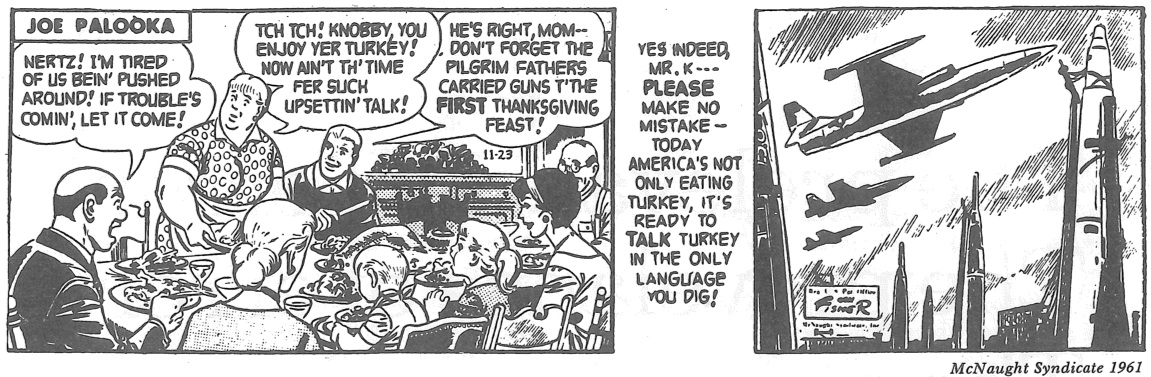

Thanksgiving finds Joe Palooka and his friends in a mood far from the spirit of the day:

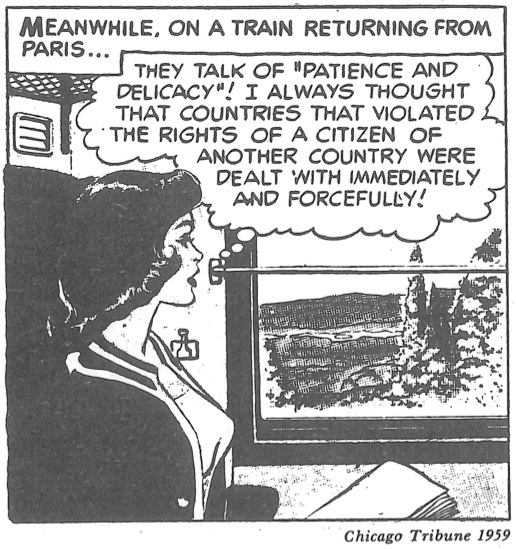

On Stage offers an editorial in favor of Big-Stick Diplomacy through the musings of Mary Perkins, whose fiance is held by the Reds:

Eyeball to eyeball, Terry argues down the weak voice of compromise, in this case belonging to a pretty, titled Englishwoman:

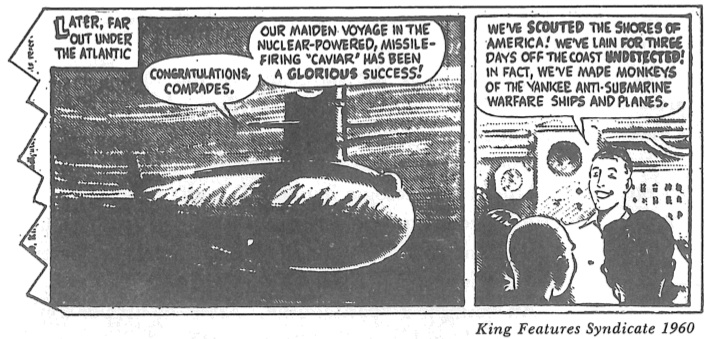

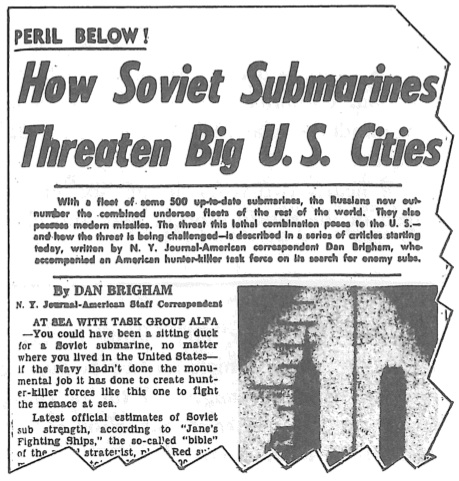

“News” overlaps art. In Buz Sawyer a Soviet submarine played hide-and-seek with the U.S. Navy for weeks before the story below appeared in the New York Journal-American, January 17, 1960:

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.