Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

On Tuesday, Dick Cheney told an audience that if Americans make the “wrong choice” on election day, “the danger is that we’ll get hit again and we’ll be hit in a way that will be devastating from the standpoint of the United States.” A flurry of stories about the comment immediately followed, many of which included quotes critical of the Bush/Cheney campaign, including a piece in USA Today headlined, “Some See Cheney’s Terror Remark as ‘Fear Strategy.'”

As a result, Cheney’s team is now rowing backward, with Cheney campaign press secretary Anne Womack assigned the oars. (” … whoever is elected, we face the prospect of a terrible attack.”) And pit bull aspirant John Edwards has gone on the attack, calling on President Bush to condemn Cheney’s “dishonorable and undignified” statement.

The appropriateness of Cheney’s comment is also being debated in opinion columns — the Los Angeles Times and New York Times look to be at odds on the issue — but there’s another reason to look at the controversy surrounding the provocative statement: It offers a window into just how much control over campaign coverage the media has ceded to the campaigns themselves. After all, it was fairly obvious to anyone who has followed the campaign, or just watched the convention, that a Republican theme has been that the current occupants of the White House are infinitely better equipped to fight the war on terror than their challengers. It’s not a large step from there to the idea that a vote for Kerry increases the likelihood that terrorists will strike again. Until Cheney’s comment, of course, no one in the campaign had spelled out the argument quite so indelicately or so explicitly — essentially, “vote for Bush or die,” as the Nation put it. As a result, prior to Cheney’s inadvertent slip from code to plain English, comment on the administration’s so-called “fear strategy,” when it appeared at all, was largely confined to opinion magazines and editorials.

It wasn’t that reporters didn’t know what was going on, but that they were reluctant to spell it out, lest they be accused of “bias” or, God forbid, “interpretation.” Cheney’s statement, which he no doubt regrets, changed all that, making it OK for reporters to treat the “fear strategy” as front-page news. It’s reminiscent of what happened with the “Dean scream” last winter or with Dan Quayle’s potato(e) moment, when reporters seized on a symbolic event to finally commit their impressions to paper. Here, once again, with the torrent of stories that greeted Cheney’s crossing the invisible line, members of the press are overreacting to a relatively minor wrinkle in order to make up for their previous reticence to assert what they had long concluded to be true.

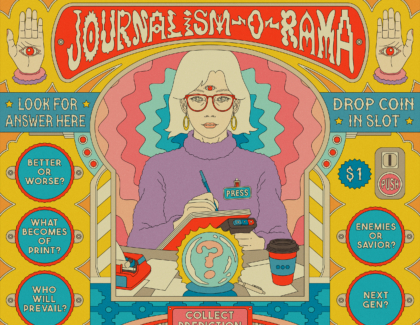

The question that arises, of course, is: Why should reporters be so docile, waiting for such a misstep from the candidates and/or their handlers? Journalism that relies on symbolic events, after all, rewards candidates for effective message management, for never quite saying what they believe. Readers are left dependent upon a misstep that may never come to discover the true impressions and conclusions of those who follow the campaign most closely. That’s in nobody’s best interest — except, perhaps, the politicians who have learned to hold their tongue.

–Brian Montopoli

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.