At some point over the past decade, Facebook stopped being a mostly harmless social network filled with baby photos and became one of the most powerful forces in media—with more than 2 billion users every month and a growing lock on the ad revenue that used to underpin most of the media industry. When it comes to threats to journalism, in other words, Facebook qualifies as one, whether it wants to admit it or not.

Facebook’s relationship with the media has been a classic Faustian bargain: News outlets want to reach those 2 billion users, so they put as much of their content as they can on the network. Some of them are favored by the company’s all-powerful (and completely mysterious) algorithm, giving them access to a wider audience to pitch for subscriptions or the pennies worth of ad revenue they receive from the platform.

ICYMI: The New Yorker publishes a salacious Trump scoop

But while many media outlets continue to pander to Facebook, even some of the digital-media entities that have catered to the company seem to be struggling. Mashable, which laid off much of its news staff to focus on video for Facebook, is being acquired by Ziff Davis for 20 percent of what it was valued at a year ago, and BuzzFeed reportedly missed its revenue targets for 2017 and had to lay off a number of editorial staff.

Facebook continues to move the goalposts when it comes to how the News Feed algorithm works. In January, the company said that it would be de-emphasizing posts from media outlets in favor of “meaningful interactions” between users, and suggested this could result in a significant decline in traffic for some publishers.

The fact that even Facebook’s closest media partners like BuzzFeed are struggling financially highlights the most obvious threat: Since many media companies still rely on advertising revenue to support their journalism, Facebook’s increasing dominance of that industry poses an existential threat to their business models.

ICYMI: The story BuzzFeed, The New York Times and more didn’t want to publish

According to a recent estimate by media investment firm GroupM, Google and Facebook will account for close to 85 percent of the global digital ad market this year and will take most of the growth in that market—meaning other players will shrink. “This is exceedingly bad news for the balance of the digital publisher ecosystem,” the firm reported.

While it may be tempting to see Facebook as an evil overlord determined to crush media companies and journalists under its boots, most media companies find themselves in this predicament because they failed to adapt quickly enough, so in a sense they only have themselves to blame.

“Did God give us that (advertising) revenue? No,” says CUNY journalism professor Jeff Jarvis. “It wasn’t our money, it was our customers’ money, and Facebook and Google came along and offered them a better deal.” The problem, says Jarvis, whose News Integrity Initiative counts Facebook as a donor, is that “we didn’t change our business models. We insist on maintaining the mass-media business model, and that’s more of a problem than social media.”

Nobody believes Mark Zuckerberg woke up one morning and decided to destroy the media industry. His company’s behavior is a lot more like an elephant accidentally stepping on an ant—something that has happened while Facebook has gone about its business.

“Facebook is a threat not necessarily because it’s evil but because it does what it does very well, which is to target people for advertisers,” says Martin Nisenholtz, former head of digital strategy at The New York Times. The question, he says, is “has it become so dominant now that it’s become essentially a monopoly, and if so what should publishers do about it?”

As well-meaning as it may be, there’s no question Facebook’s dominance of social distribution, and the power it gives the company to command attention, represents a direct threat to media companies. It’s about control.

As digital advertising continues to decline as a source of revenue thanks to Google and Facebook, many media companies are having to rely increasingly on subscriptions. But the readers they want to reach are all on Facebook consuming content for free.

Places like The New York Times or The Wall Street Journal have the kinds of international brands that will allow them to continue to be advertising destinations and also get the lion’s share of subscriptions. But where does that leave mid-market papers that don’t have the scale or the reach?

Most media companies find themselves in this predicament because they failed to adapt quickly enough, so in a sense they only have themselves to blame.

“The brutal truth for publishers is that, absent the cost structure and differentiation necessary to create a sustainable destination site that users visit directly, they have no choice but to bend to Facebook’s wishes,” technology analyst Ben Thompson wrote in his newsletter, Stratechery. “Given how inexpensive it is to produce content on the internet, someone else is more than willing to take your share of attention.”

As a result, publishers risk becoming commodity suppliers to Facebook. And not only are commodity suppliers unable to demand very much in the form of pay, but they can also be replaced easily—or asked to pay for the right to reach the users they originally reached for free.

ICYMI: Jonah Peretti: Everything is fine

Either way, as Facebook increases its control, “they’ll decide which brands they are going to elevate and which they will filter out,” says Emily Bell, director of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia. “There’s an ethical view that this is a terrible state of affairs, since it means that Facebook effectively decides which media outlets survive and which don’t.”

Author and journalism professor Dan Gillmor recently described a future in which “we will be living in the ecosystem of a company that has repeatedly demonstrated its untrustworthiness, an enterprise that would become the primary newsstand for journalism and would be free to pick the winners via special deals with media people and tweaks of its opaque algorithms. If this is the future, we are truly screwed.”

In addition to the economic threat it represents to media companies, Facebook also arguably poses a threat to journalism itself. Into this bucket we can throw things like fake news and misinformation, which works primarily because Facebook focuses on engagement—time spent, clicks, and sharing—rather than quality or value.

In many ways, sociologists say, Facebook is a machine designed to encourage confirmation bias, which is the human desire to believe things that confirm our existing beliefs, even if they are untrue. As a former Facebook product manager wrote in a Facebook post: “The news feed optimizes for engagement, [and] bullshit is highly engaging.”

Facebook has announced a number of attempts to fix its misinformation problem, including a fact checking project that adds the “disputed” tag to stories that have been flagged by partners. But those efforts have been stymied by the fact that some of Facebook’s problems appear to be baked into the platform (and into the company’s relentlessly efficient DNA).

Late last year, Facebook announced that it was dropping the “disputed” tag because it proved to be ineffective in stopping people from sharing misinformation, and in fact may have actually achieved the opposite goal, by reinforcing people’s erroneous beliefs about certain topics.

Given the platform’s repeated misunderstanding of its role in the information ecosystem, some believe that Facebook may simply not be a great place for journalism to live. Digital-journalism veteran David Cohn has argued that the network’s main purpose is not information so much as it is identity, and the construction by users of a public identity that matches the group they wish to belong to. This is why fake news is so powerful.

“The headline isn’t meant to inform somebody about the world,” wrote Cohn, a senior director at Advance Publications, which owns Condé Nast and Reddit. “The headline is a tool to be used by a person to inform others about who they are. ‘This is me,’ they say when they share that headline. ‘This is what I believe. This shows what tribe I belong to.’ It is virtue signaling.”

Twitter suffers from a similar problem, in the sense that many users seem to see their posts as a way of displaying (or arguing for) their beliefs rather than a way of exchanging verifiable news. But Facebook’s role in the spread of misinformation is orders of magnitude larger than Twitter’s: 2 billion monthly users versus 330 million.

Facebook watchers, including some former and current employees, say many of the company’s journalism problems are exacerbated by the fact that the news simply isn’t a core focus for the company, and likely never will be.

In recent years, as heat on the company has risen, Facebook has tried to pretend that isn’t the case. Zuckerberg has gone from saying that it was “a crazy idea” to suggest fake news on the network affected the US election to admitting that Facebook does play a role in the dissemination of misinformation, and that Russian troll factories used the platform in an attempt to meddle with the election.

If you move fast and break democracy, or move fast and break journalism, how do you measure the impact of that—and how do you go about trying to fix it?

Facebook has rolled out a range of well-meaning journalistic efforts, including its partnership with fact-checking organizations, the Facebook Journalism Project—which is aimed at helping newsrooms get more digitally savvy—and the News Integrity Initiative, which Jarvis helped launch last year with funding from Facebook and others.

But these tend to come off looking more like public relations vehicles, as the company tries to stay ahead of federal regulators and others who might want to impose legal restrictions on what it can and cannot do.

“Throwing money at things is a Band-Aid,” says a former staffer. “They’re not grappling with the real problems their dominance is causing. I left because it became frustrating to know that they weren’t taking seriously the impact they were having on journalism and the news.”

It’s not that Facebook doesn’t care about things like fake news, it’s that it doesn’t care enough. And the reason why is the same as it is for Google (which has a number of its own well-meaning efforts aimed at journalism)—because ultimately those issues don’t affect the central business of the company, which is to connect everyone on the planet and generate as much advertising revenue as humanly possible.

Former Facebook employees say the engineering-driven, “move fast and break things” approach worked when the company was smaller but now gets in the way of understanding the societal problems it faces. It’s one thing to break a product, but if you move fast and break democracy, or move fast and break journalism, how do you measure the impact of that—and how do you go about trying to fix it?

“I think there’s a possibility that they just don’t know what to do” about these larger problems, says Nisenholtz. “I think there’s a chance they don’t have the people in their organization or the DNA to even understand what is going on or what to do about it. I’m fundamentally optimistic about Facebook’s desire to help, but I’m not as optimistic about its ability to help.”

Jarvis, however, believes Facebook does care, and is prepared to devote its considerable weight to solving the problem. “I’ve talked to Chris Cox, the head of product at Facebook, and I believe he cares deeply about news. I think Mark Zuckerberg cares. We have to reinvent journalism, and we should be doing it in partnership with Facebook and Google because they’re a lot fucking smarter about it than we are.”

But it’s not the smarts of the Facebook employee that anyone doubts. It’s whether this company, literally engineered to do one thing incredibly well, can reprogram itself to care about something—journalism—it knows very little about.

As much of a threat as Facebook currently represents for the media industry, it could get much worse. The company could, for instance, continue to vacuum up even more of the advertising market to the point where ads are no longer a viable revenue source for media companies at all. For some, that would mean going from ads contributing as much as 60 percent of revenue to zero.

“There are parts of the media business model that are just broken, like the advertising business—the distribution bottleneck is gone,” says Bell. “What the new journalistic business looks like, that can not just survive but thrive in this new world, we haven’t really figured it out yet.”

Could advertising disappear completely as a viable revenue source? Jason Kint of Digital Content Next, a lobby group that includes some of the largest media brands in the country, says he sees Google and Facebook continuing to dominate “programmatic” or automated advertising. But he believes there is still the potential for other forms of advertising—high-value display, for example—to continue generating revenue for media companies.

But even those new possibilities are likely to hit the Facebook algorithmic wall. “Either the advertising business as we know it goes away, or you survive as a media outlet because you are in Facebook’s favor, either algorithmically or otherwise,” says one veteran journalist, who didn’t want his name used because he has to work with Facebook. “There’s no precedent in terms of the size and dominance of it as a media entity, and no one has any idea what to do about it. We are in uncharted territory here.”

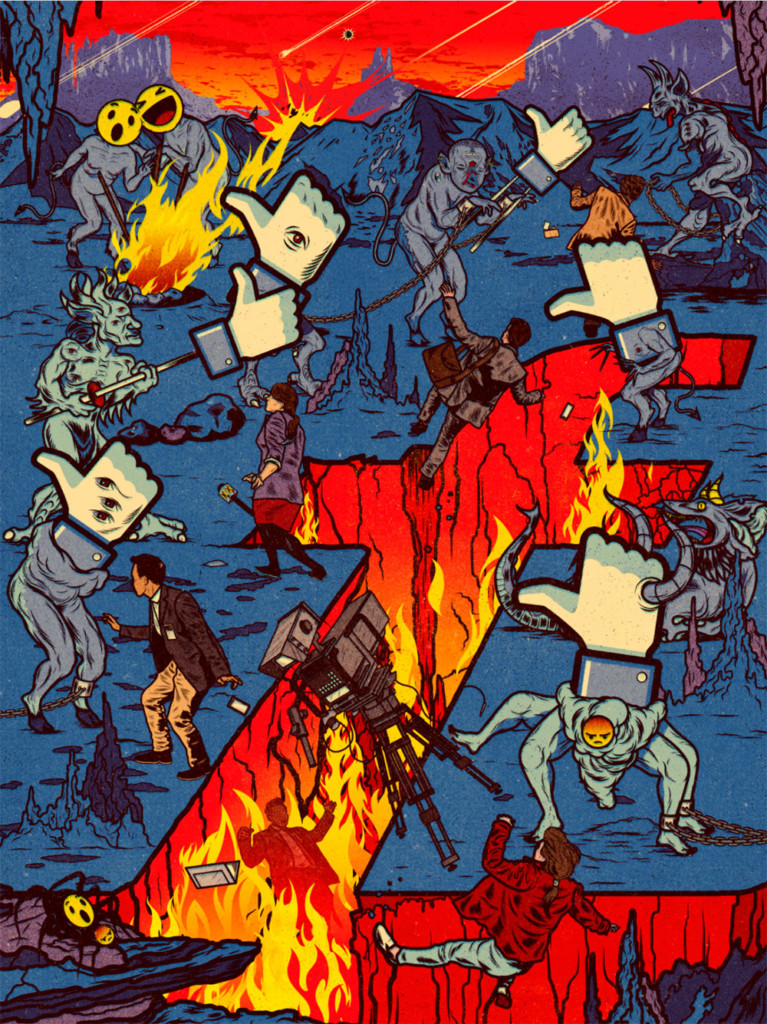

Illustration by Diego Patiño

As bad as scraping for advertising revenue might be, there’s another way the Facebook threat could actually get worse: Instead of continuing to be a primary platform for news companies and trying to strike relationships with them, the company could decide to simply wash its hands of news entirely, either because it isn’t generating enough revenue, or because it has become too much of a political headache.

For Facebook, it has to be distracting to devote so much of its time and energy to congressional sub committees or European Union directives related to “fake news” and Russian trolls. And for all its attempts to help media companies with revenue sharing and fact-checking and other initiatives, it inevitably gets criticized for not doing enough.

In a larger sense, news—meaning journalistic stories produced by credible publishers—likely represents a small proportion of the content that appears on Facebook, most of which is composed of family photos or posts about friends and co-workers. News may encourage engagement, but is it worth the hassle?

Facebook’s decision in January to de-emphasize publisher links in the News Feed is a step away from news, a move some have argued might actually be good for media companies. An even bigger move would be a split News Feed, where the majority of content in the main feed is related to personal relationships, and a separate feed includes traditional news articles from mainstream outlets.

We got a glimpse of what that might look like earlier this year, when Facebook tested a split feed in several Asian and Eastern European countries. News outlets who work in those countries said their reach on the social network fell by as much as 60 percent overnight.

Ironically, some criticized Facebook for these experiments because they said the company was messing around with what has become a key source of news for people in struggling democracies like Cambodia, where traditional media is untrustworthy. In many ways, this reinforced the power that Facebook has developed over news consumption, not just in the US but around the world.

Could they decide just to give up on news, or relegate it to the sidelines? “I feel like there’s a real chance that they might just decide it’s too much trouble, too much of a PR mess, and they’re not even making that much money from it to begin with,” says one former staffer. “But the genie is kind of out of the bottle now. I’m not sure they can go back at this point.”

To really come to grips with what its size and influence have wrought both in journalism and society at large, Facebook is going to have to not only change its outlook but also its culture. But is that even possible at this stage? Can a company that became a $500 billion colossus by thinking in one way start to think in a different way?

“Facebook is going to be an important institution, even if it decides it doesn’t want to actually produce journalism,” says Bell. “If it’s here to stay, it needs to be part of figuring this problem out. My worry is that they only see things in market terms, so it’s all about market share. And my biggest fear is that they just sort of give up and decide it’s just not part of their core vision.”

After all, the company didn’t set out to kill anything, including the media industry, says one former staffer. “Zuck is just a very competitive guy, and he wanted to build the largest company he could. And now they’ve done it—he’s won. But they fundamentally don’t know how to deal with it.”

In a way, Facebook is like a band of revolutionaries who don’t know what to do once they manage to topple the dictator and actually become the government. And we are all living in the world that they have created for us, whether we like it or not.

ICYMI: The New York Times sparks outrage with profile

A timeline of turmoil

While Facebook has become enormously influential as a distributor of news, that sway hasn’t come without pain. In the past decade, the company has been criticized for helping to spread scams, hoaxes, and fake news, all while becoming one of the biggest media companies on the planet.

September 2006: The hated news stream

Facebook launches the News Feed. A blog post describes it as a stream that “highlights what’s happening in your social circles on Facebook.” Many users hate it.

September 2011: The reader that wasn’t

Facebook launches its “social news reader” apps with The Washington Post and The Guardian. But the algorithm is later changed so many users don’t see them.

January 2012: Advertising is introduced

The company starts showing advertising inside the News Feed. That year, Facebook’s ad revenue is $4 billion. By 2016 it would hit almost $27 billion.

December 2013: A newspaper of one’s own

Mark Zuckerberg says he wants to make the News Feed “the best personalized newspaper in the world.” In 2014 the company launches a standalone app called Paper.

January 2015: Scam alert, version 1.0

After criticism of hoaxes and scams, Facebook says it will crack down, but says “we are not reviewing content and making a determination on its accuracy.”

May 2015: Arrival of instant articles

Facebook launches Instant Articles, a feature that makes mobile pages load faster. Initial launch partners include BuzzFeed, The New York Times, and National Geographic.

May 2016: Conservative controversy

Gizmodo reports that Facebook’s “trending topics” team routinely inserts or removes news articles from the section, and that it does so with conservative news sites in particular.

November 2016: The election effect

Zuckerberg says the idea that fake news affected the US election is “crazy.” But a month later Facebook says it will work with users and third-party verification services to identify fake articles.

April 2017: In the DC spotlight

Facebook admits that Russian government agents used fake accounts to influence the US election, and later appears before Congress after admitting Russian trolls bought political ads.

January 2018: Personal over political

Facebook announces a change to the News Feed to prioritize personal posts over news content, and warns publishers their traffic from the social network will likely decrease.

Mathew Ingram was CJR’s longtime chief digital writer. Previously, he was a senior writer with Fortune magazine. He has written about the intersection between media and technology since the earliest days of the commercial internet. His writing has been published in the Washington Post and the Financial Times as well as by Reuters and Bloomberg.